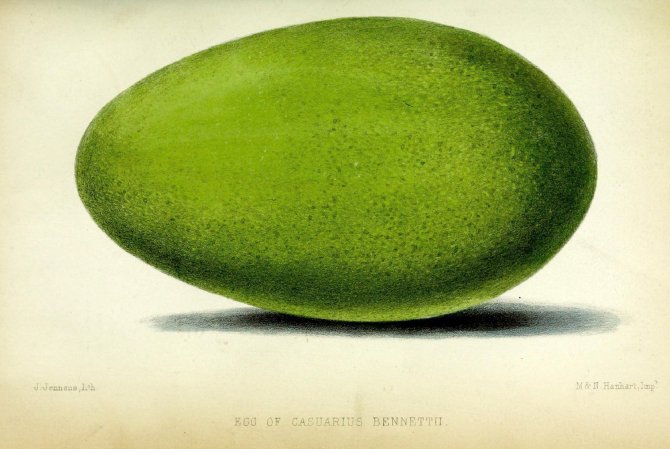

If you think Australian animals are terrifying now, just imagine roaming the outback and encountering a sheep-sized echidna. You know, those egg-laying mammals with weird spiny fur—except this one was giant and had a long, pointed beak. Megafauna like that dominated the landscape until about 46,000 years ago when they nearly all died out.

And it may be that humans put those majestic sheep-chidnas six feet under the red soil.

This has been a massive debate in the archaeological world for some time, because the timing has been hard to pin down. Humans were thought to have arrived in Australia anywhere from 47-60,000 years ago, which might not have given them enough time to wreak so much havoc on the local megafauna. It just wasn’t clear where in that range humans truly migrated into the area. But if there was evidence that they arrived more like 65,000 years ago, well…that could change things.

A new archaeological study suggests just that. Published in Nature on Wednesday, the paper details findings from a dig site in northern Australia. All told the group pulled up some 11,000 artifacts that they were able to date using a combination of carbon dating and optically stimulated luminescence, which calculates when quartz particles were last exposed to sunlight.

Their work also pushes back the time when humans left Africa. If they’d already arrived in Australia by 65,000 years ago, that means their original departure must have happened significantly before then to allow time for migration all the way to the far reaches of Asia. Just consider for a moment that this means more than 65,000 years ago, early humans not only ventured across entire continents, but also looked out at the seemingly endless sea and decided to built boats. Imagine looking at the ocean, having no idea what was on the other side and completely lacking sophisticated navigation tools, and thinking “yeah, I could cross cross that.”

But that’s just what they did. And when they arrived in Australia, it was to a land filled with enormous plants and animals that existed nowhere else on Earth. Kangaroos are intimidating as it is—back then there were 10-foot-tall ones weighing 500 pounds. Today’s are under seven feet tall. Oh, and there was an ancient koala that was about a third larger than the modern version. Plus (bonus!), the largest marsupial to ever live: the Diprotodon. Just imagine what you’d get if you crossed a rhinoceros with a koala, and you’ve got a pretty solid mental image of these guys. They stood about 6.5 feet tall, over 9 feet long, and weighed over 6,000 pounds.

Aboriginal drawings seem to depict a lot of these ancient animals. Descendents of those aboriginals, the Mirarr, oversaw the dig and will get the artifacts back once the study is complete. The artifacts don’t just show that humans existed in the area 65,000 years ago. They show that they had surprisingly complex lives. The site was home to Australia’s oldest seed grinding tool and to the world’s oldest ground-edge stone axe. Plus, there’s evidence of ancient paintings using ochre and other pigments, perhaps combined with mica-like additives to make the art sparkle.

These ancient aboriginals probably didn’t know they were driving animal extinctions, even if that was actually the case. Yes, it’s possible that early humans hunted some animals to extinction. But it’s also possible that the aboriginals’ use of fire-stick farming changed the ecosystem so rapidly that many animals simply died out.

Both theories have evidence to back their claims, and both have critics who point out their flaws. As ever in the world of science, this won’t settle the debate—it just adds weight to one side. Another day, another discovery, another giant echidna that could have been.