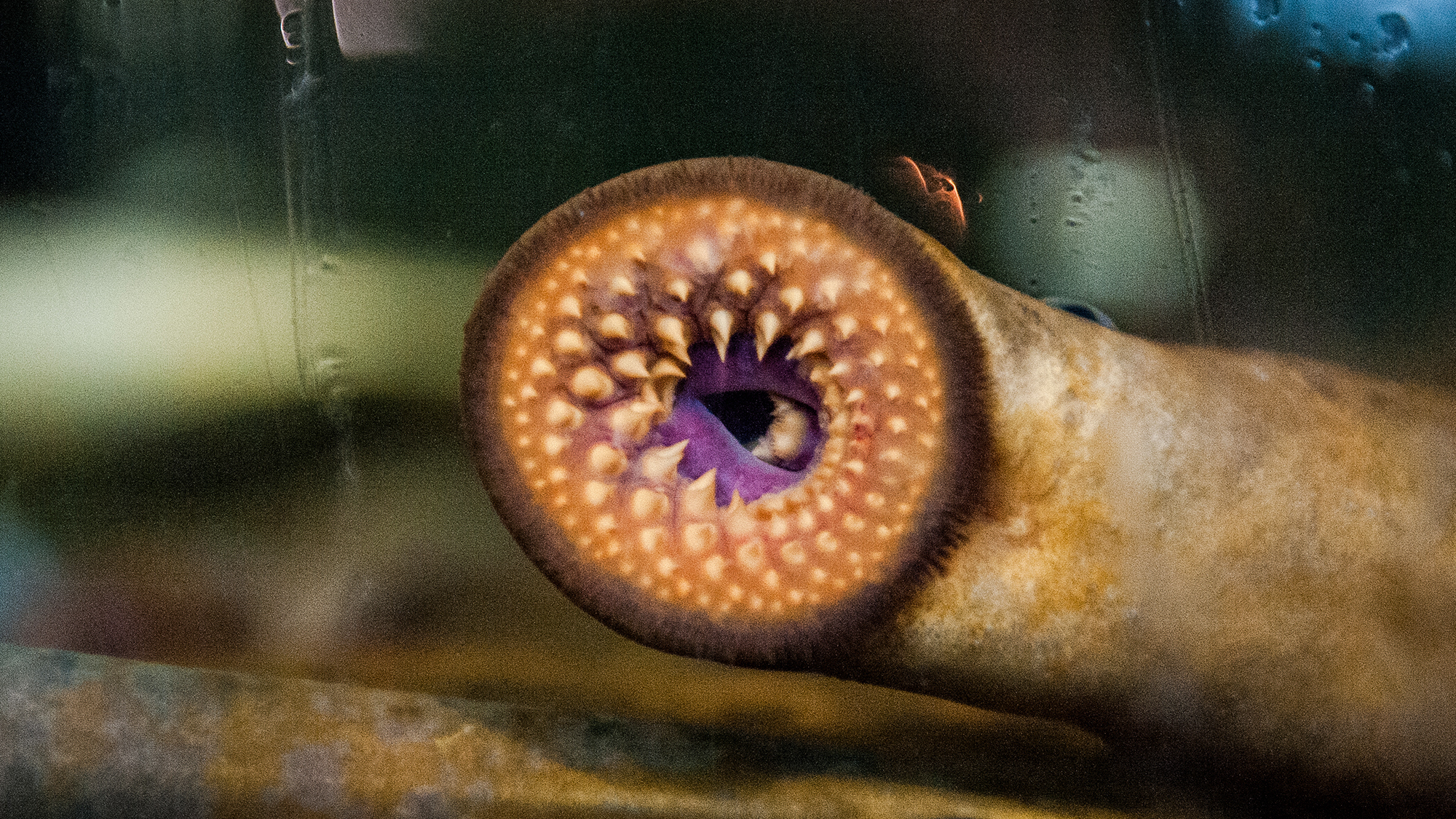

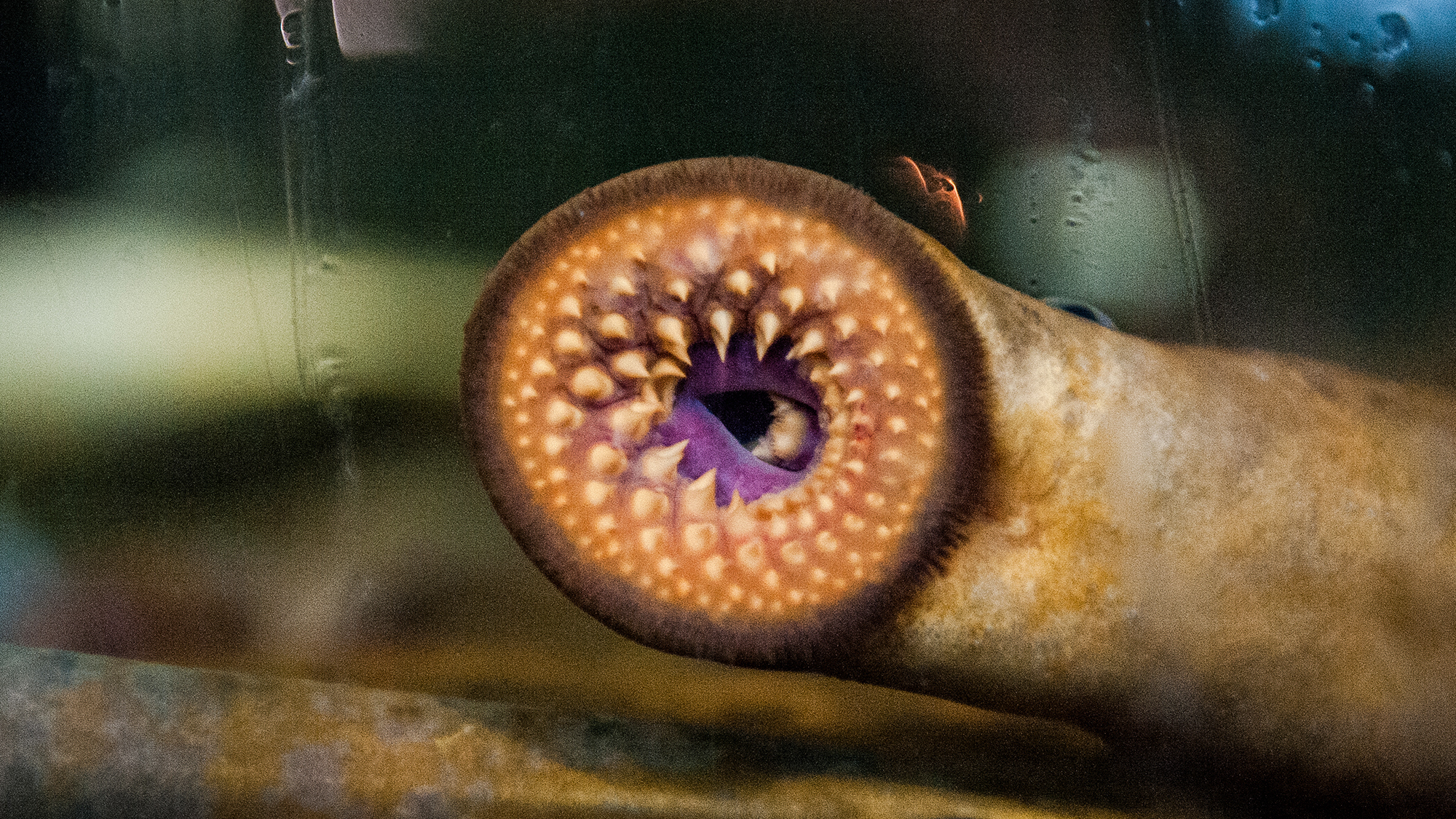

Lampreys look like something out of a horror movie, with their sucky mouths chock full of teeth, eel-like bodies, and parasitic behaviors. These “water vampires” represent a bit of an evolutionary fork in the road between vertebrates and invertebrates, and the scientific debate about just how closely related we are to these carnivorous fish has taken yet another turn.

Scientists found some evidence that lampreys have a rudimentary sympathetic nervous system–which is believed to control the fight-or-flight reaction in vertebrates. The findings are detailed in a study published April 17 in the journal Nature and could prompt a rethink of the origins of the sympathetic nervous system.

Lampreys are the closest living organisms scientists have to studying the fish ancestors that vertebrates evolved from some 550 million years ago. They belong to an ancient vertebrate lineage called Agnatha–or jawless fish. Some scientists believe that they represent the earliest group of vertebrates that is still living and can give us an evolutionary window into all vertebrate ancestors. Other scientists question the theories due to a lack of lamprey evidence in the fossil record.

[Related: Giant prehistoric lamprey likely sucked blood—and ate flesh.]

Scientists previously believed that lampreys did not have sympathetic neurons. These neurons are part of the sympathetic nervous system, a system of nerves that target the internal organs throughout the body including the gut, pancreas, and heart. The system works together to respond to dangerous or stressful situations. It also helps an organism’s body maintain homeostasis, making sure that the heart keeps pumping, the digestive system keeps moving, and more.

In this new study, a team used lampreys to look at how developmental changes may have promoted the evolution of vertebrate traits like fight-or-flight. They found evidence of the types of stem cells that eventually form sympathetic neurons. The presence of these cells in lampreys could revise the timeline of when the sympathetic nervous system began to evolve.

“Over a hundred years of literature has suggested that lamprey lack a sympathetic nervous system,” study co-author and California Institute of Technology biologist Marianne Bronner said in a statement. “Surprisingly, we found that sympathetic neurons do, in fact, exist in lamprey but arise at a much later time in lamprey development than expected.”

Bronner and her team studied neural crest cells. These are a kind of stem cells that are specific to vertebrates and give rise to the multiple cell types found throughout the body. Scientists previously believed that lampreys lacked the neural crest-derived precursors, or progenitors, that ultimately build the sympathetic nervous system.

According to Bronner, researchers previously looked for evidence of a sympathetic nervous system too early in lamprey development compared to other animals. For example, the sympathetic nervous system forms in the first two to three days of development in birds.

[Related: You might have more in common with the sea lamprey than you realize.]

Study co-author and Cal Tech evolutionary biologist Brittany Edens looked at the neural crest–derived progenitor cells in lampreys that ultimately give rise to sympathetic neurons. She found that in lampreys, the neural crest–derived progenitors appear much later than other animals. They can appear as long as one month after fertilization. The cells also do not fully mature into neurons until about four months of development, during the fish’s larval stage.

It is still not known whether the sympathetic nervous system of lampreys controls fight-or-flight-like behaviors similar to other vertebrates. According to the team, these findings suggest that the developmental program that controls the formation of sympathetic neurons remains across all vertebrates, from lamprey to mammals.