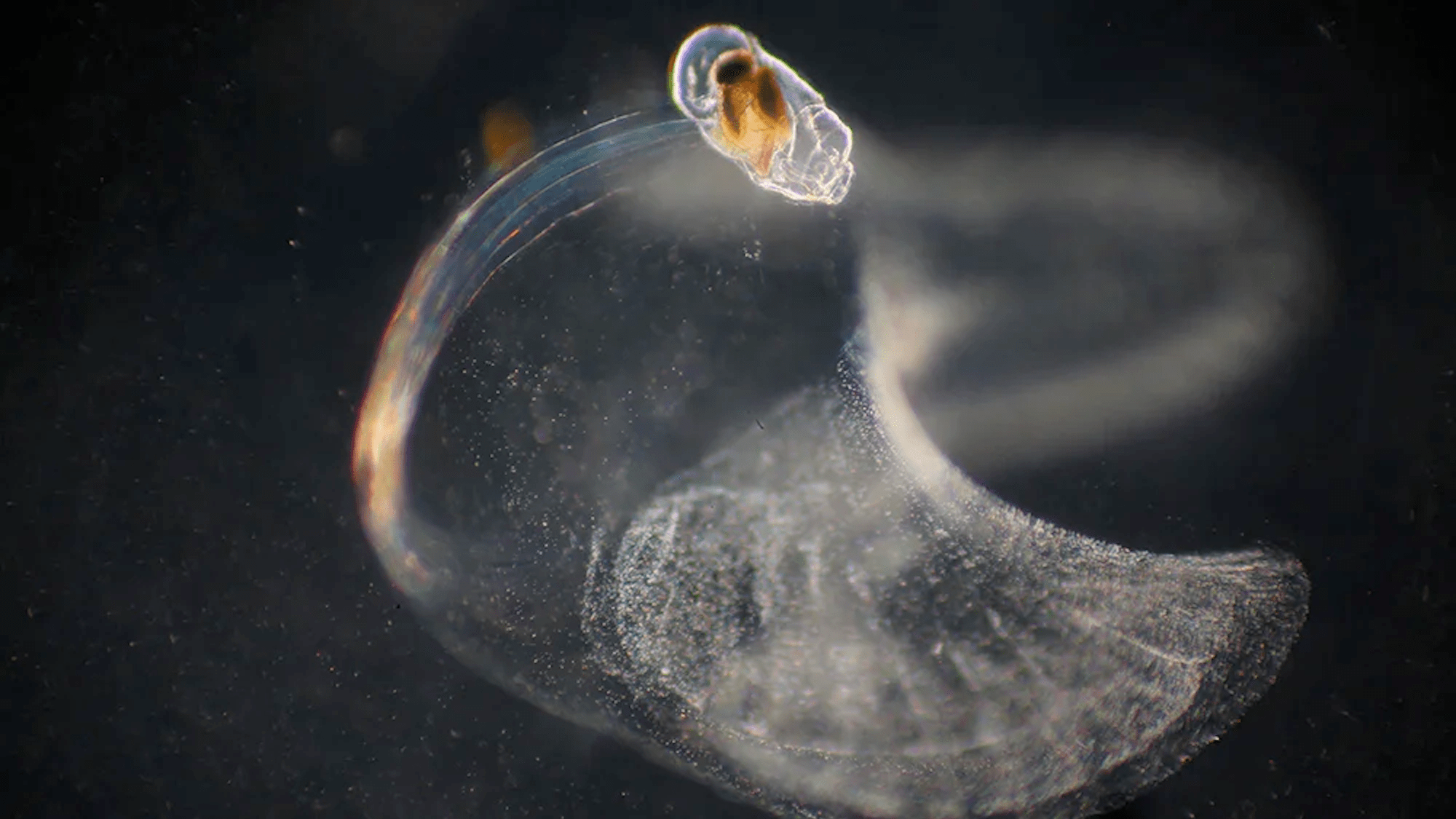

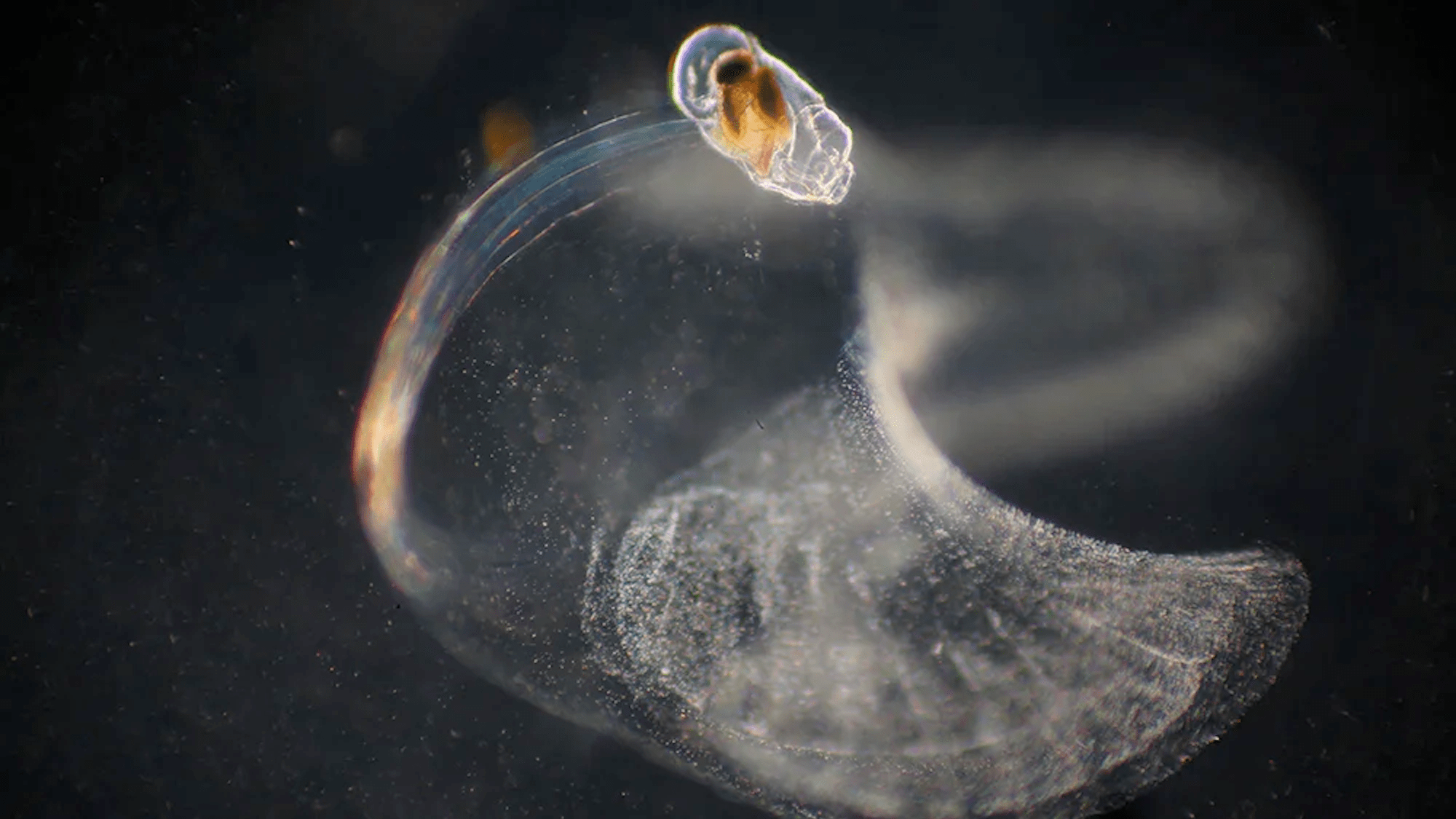

When it’s time for a snack, the miniscule sea creature known as Oikopleura dioica gets gross. At barely a millimeter long, the filter-feeding larvacean excretes and encases itself in a jelly-like substance to form what biologists dub a “mucus house” or a “snot palace.”

A tadpole-like O. dioica’s tiny, temporary abodes are biological wonders—using its tail, the larvacean creates its own pump-filtration system capable of capturing and propelling food particles towards its mouth. Now, researchers believe the snot palace’s interior fluid dynamics could inspire a new generation of artificial pump systems for wastewater treatment plants and air filtration systems.

[Related: These animals build palaces out of their own snot.]

“It’s so cool. It’s a pretty complex structure,” University of Oregon biology research assistant Terra Hiebert said in a January 8 profile.

Hiebert and collaborators detailed their work in a study recently published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface. To better understand a snot palace’s inner workings, Hiebert’s team traveled to a larvacean breeding facility in Bergen, Norway to analyze the creatures’ movements using a high-speed video camera attached to a microscope. In reviewing the footage, researchers noticed how an O. dioica’s tail shifted responsibilities depending on whether or not it was time to eat. While simply swimming near the ocean’s surface, the tail wriggles side-to-side to push the creature forward through water, but it’s a different story once inside the mucus house.

Once encased in the gelatinous substance, O. dioica’s appendage actually touches the interior in multiple locations. When the tail wiggles in these moments, the animal doesn’t move nearly as much. Instead, the tail sticks and unsticks from the casing “like Velcro,” according to the University of Oregon, and the snot palace subsequently inflates like a balloon as nearby particles collect on the surface. Each movement pushes these particles along, eventually in the direction of the larvacean’s mouth. Once the mucus filtration system is too clogged to function, O. dioica simply sheds its makeshift restaurant, which then sinks into the ocean and eventually decomposes. In approximately 3-to-4 hours, the larvacean repeats the process all over again.

Although O. dioica’s structure fits the bill for a peristaltic pump, it’s not the most common design. Usually, a peristaltic pump’s fluid motion originates through external pressure, such as contractions in your colon to push along waste. In a snot palace, however, the momentum derives from within the pump itself via the larvacean’s tail. Researchers believe designers could adapt this alternative setup for engineering new wastewater treatment plants or air filtration systems—hypothetically, locating any moving parts within the pump could protect the overall setup from wear-and-tear.

If this proves true, urban planners could have snot palaces to thank for cleaner, more efficient municipal water facilities.