Observers have documented multiple animal species using plants for self-medicinal purposes, such as great apes eating plants that treat parasitic infections or rubbing vegetation on sore muscles. But a wild orangutan recently displayed something never observed before—he treated his own open wound by activating a plant’s medical properties using his own spit. As detailed in a study published May 2 in Scientific Reports, evolutionary biologists believe the behavior could point toward a common ancestor shared with humans.

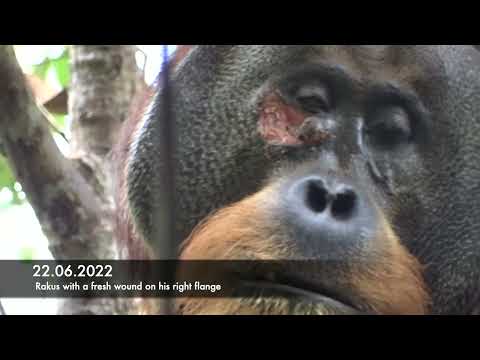

The discovery occurred within a protected Indonesian rainforest at the Suaq Balimbing research site. This region, currently home to roughly 150 critically endangered Sumatran orangutans, is utilized by an international team of researchers from the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior to monitor the apes’ behavior and wellbeing. During their daily observations, cognitive and evolutionary biologists noticed a sizable injury on the face of one of the local males named Rakus. Such wounds are unsurprising among the primates, since they frequently spar with one another—but then Rakus did something three days later that the team didn’t expect.

After picking leaves off of a native plant known as an Akar Kuning (Fibraurea tinctoria), well-known for its anti-inflammatory, anti-fungal, and antioxidant properties, as well as its use in traditional malaria medicines, Rakus began to chew the plant into a paste. He then rubbed it directly on his facial injury for several minutes before covering it entirely with the mixture. Over the next few days, researchers noted the self-applied natural bandage kept the wound from showing signs of infection or exacerbation. Within five days, the injury scabbed over before healing entirely.

Such striking behavior raises a number of questions, particularly how Rakus first learned to treat his face using the plant. According to study senior author Caroline Schuppli, one possibility is that it simply comes down to “individual innovation.”

“Orangutans at [Suaq] rarely eat the plant,” she said in an announcement. “However, individuals may accidentally touch their wounds while feeding on this plant and thus unintentionally apply the plant’s juice to their wounds. As Fibraurea tinctoria has potent analgesic effects, individuals may feel an immediate pain release, causing them to repeat the behavior several times.”

[Related: Gorillas like to scramble their brains by spinning around really fast.]

If this were the case, it could be that Rakus is one of the few orangutans to have discovered the benefits of Fibraurea tinctoria. At the same time, adult orangutan males never live where they were born—they migrate sizable distances either during or after puberty to establish new homes. So it’s also possible Rakus may have learned this behavior from his relatives, but given observers don’t know where he is originally from, it’s difficult to follow up on that theory just yet.

Still, Schuppli says other “active wound treatment” methods have been noted in other African and Asian great apes, even when they aren’t used to disinfect or help heal an open wound. Knowing that, “it is possible that there exists a common underlying mechanism for the recognition and application of substances with medical or functional properties to wounds and that our last common ancestor already showed similar forms of ointment behavior.”

Given how much humans already have in common with their great ape relatives, it’s easy to see how this could be a likely explanation. But regardless of how Rakus knew how to utilize the medicinal plant, if he ever ends up scrapping with another male orangutan again, he’ll at least know how to fix himself up afterwards.