When it comes to practicality, geodesic domes are a contractor’s worst nightmare. Where can you get windows that conform to hexagonal panels? Where should you install the pipes? Would a chimney look out of place? In spite of all these questions, we spent a good portion of the 1970s and ’80s touting geodesic structures as the next big suburban fad.

The trend began, of course, after R. Buckminster Fuller received a patent for his geodesic domes in 1954. Although Fuller’s idea wasn’t entirely original, he is credited for formulating the structure’s mathematics. Initially commissioned by the military and by specialized companies, Fuller’s geodesic domes went on to become a viable solution to the postwar housing crisis. While most families continued buying conventional houses, fans of the geodesic dome spent several decades promoting it as a super strong, easy-to-build vacation home. If a second home were too expensive, you could always pitch stylish mini domes on your lawn.

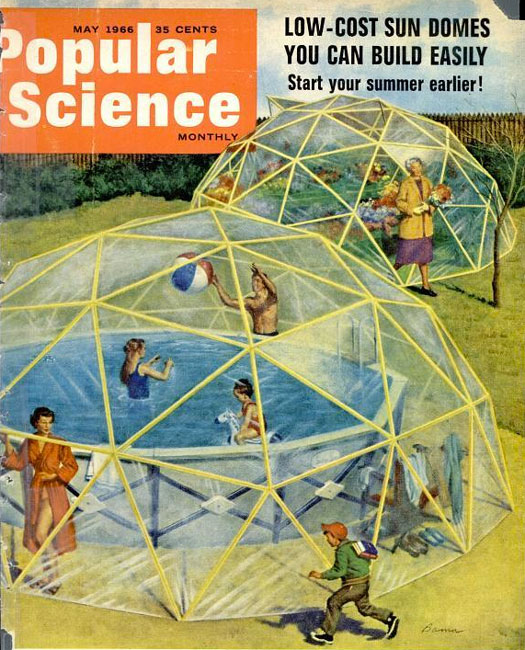

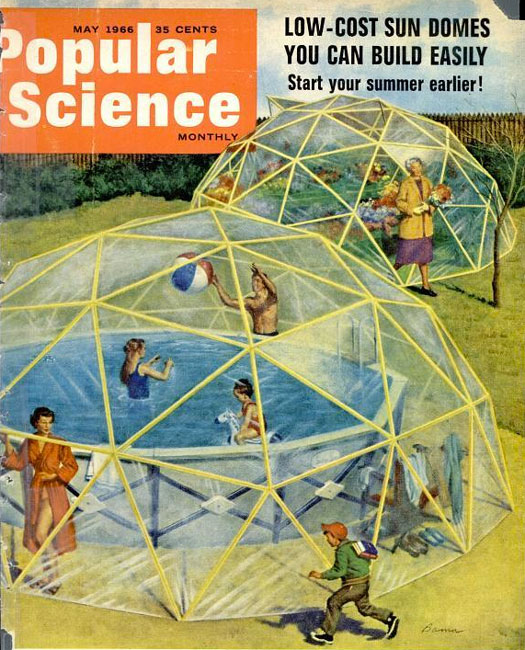

Suffice to say, the outdoor sun dome was a far simpler project than the numerous DIY geodesic houses advertised on our pages. The plastic structure reflected the dome house’s properties on a small and manageable scale: it was strong, it was easily assembled, and its interior was always well-insulated. On sunny days, the inside of the plastic dome was reportedly 20 to 30 degrees warmer than the outside temperature, meaning that you could feasibly use it as a weather shield for year-round swimming.

Likewise, the geodesic home promised to cut people’s electric bills at least 30 percent. Despite their inconvenient shape, geodesic domes require the least amount of surface area for any given interior volume. The inside of a geodesic home is not only spacious, but it distributes coolness and heat more effectively than a rectangular house. Because of the dome’s superior insulation, families who purchased these houses claimed energy savings of up to 50 percent.

So why did geodesic homes fail to cross into the mainstream? Simply put, the novelty of their construction couldn’t justify the work it took to get past code requirements and challenges with interior design. Tradition is not easily overridden. Building materials cater to rectangular structures, not rounded ones, and domes tend to leak between the seams during rainstorms.

While geodesic dome homes might have fallen short of our expectations, they remain an iconic symbol of the future that never was.

Inspired by R. Buckminster Fuller’s patented geodesic structure, this plastic outdoor sun dome served as the perfect lawn accessory for readers who couldn’t wait for the onset of summer. On sunny days, the temperature inside the structure was 20 to 30 degrees higher than the temperature outside. You could use it as a pool cover, a greenhouse, a family playroom, and even as an insect shield during barbeques.

The domes came in three sizes: 16 1/2 feet, 25 feet, or 30 feet in diameter. One Popular Science reader purchased plans for the 25′ model and built it using just clear pine, polyethylene film, and a staple gun.

The South Pole might be an awful place to live, but it is the perfect location for a giant igloo. In 1971, we announced plans for the upcoming Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station, which would use a geodesic design as protection from the weight of snow. The structure would house a library, post office, science labs, and living quarters, and a communications center, among other facilities.

Construction took place during the Antarctic summers between 1971 and 1974, and as expected, it wasn’t an easy process. Crewmen not only had to work in an extreme climate, but their tents weren’t even heated enough to sustain room temperature. Still, the project surpassed our expectations. While we gave the doe a lifespan of just 10 to 15 years, it actually stayed open until 2003, when it was replaced by a two-story elevated station.

In the early 1970s, dome-shaped houses were poised as the next big trend in suburbia. Popularized in recent years by geodesic-shaped commercial structures and exhibition halls, geodesic houses presented a striking alternative to the “conventional ticky-tacky house construction” of the 60s. Despite their novel appearance, geodesic homes seemed to offer countless practical benefits. Firstly, these houses could withstand more pressure than your average rectangular building. Secondly, these homes would be delivered by mail and assembled from a kit. The process would be so straightforward that anyone, not just construction workers, would be capable of building it successfully.

Nowadays, dome houses are a rarity in residential areas. They sounded convenient in theory, but actually erecting one was more complicated than we anticipated. For one thing, the dome home’s shape made it difficult for homeowners to install standard pipes, chimneys, and even windows. Custom-made products were not only costly, but they didn’t often conform to typical building codes. Interior design was also tricky, as furniture is usually designed with rectangular floor plans in mind.

All maintenance problems aside, architects and hobbyists were eager to take on the challenge of building a geodesic home. Famed architect Lester Walker designed a project that permitted you to build the structure in small parts before assembling it as a whole. Building the dome was simple, if not repetitive, but once you finished cutting the panels, the dome could go up like a giant toy set. Walker summed up the process using an 11-step photo story, which began with the creation of a three-foot model and ended with the application of aluminum tape all over the seams. Once done, the structure proved to be water-tight and well-ventilated. Hurricane Agnes hit the dome’s surrounding area just days after its completion, but the structure managed to survive without a single leak.

During the peak of dome mania, Bucky Fuller himself contributed an article promoting geodesic houses. According to Fuller, there are three obstacles to the acceptance of geodesic houses in America. First, dome houses look weird. We’re so used to living in rectangular structures that can’t imagine living any other way. Second, most contractors are hesitant to work on a building that defies traditional parameters. Finally, building codes were created for structures that contain 90 degree angles. In order to build a dome, you need to final for city approval, which would be hard to attain without some expert engineering on your part.

As a solution, Fuller presented our readers with plans for a Hexa-Pent dome, which provided detailed blueprints for contractors to follow. Unlike other dome homes, which used individually strutted triangular panels, the Hexa-Pent was assembled with hexagons and pentagons. This saved labor and materials while preserving the dome’s trademark geodesic appearance.

According to Lester Walker’s website, his Frame Hung Dome ended up selling over 3000 sets of construction plans. Naturally, a good portion these consumers were our own readers, who clamored for advice on decorating their new homes. Two years after the original article’s publication, Les Walker provided us with two design schemes — one for families, and the other for a young couple. The image on the left depicts a simple plan for the latter. Utilities would be situated inside of a pentagon core. You could install the kitchen on one side of this structure, while two other corners could be partitioned for the bathroom and a small closet. If you wanted to keep the dome’s floorspace open, you could install your bed on top of the core.

We started running ads for built-it-yourself dome homes during early 1980s, when families began considering these structures for their practical features more than for their kooky appearance. Although geodesic houses reportedly experienced leakage problems and could attract unwanted attention from curious passersby, the spaciousness they offered was a dream come true for those who needed to save on electric bills. Heating costs were 30 to 50 percent cheaper than they were in conventional structures with the same surface area. In addition to touting their low energy costs, advertisements like this one focused on dome houses’ bold design, resistance to earthquakes, and ease of assembly. Despite their size, Cathedralite domes could supposedly go up in just 8 hours.

Apparently, the only thing more fun than a geodesic family home is a geodesic jungle gym. This wooden swing set, which was constructed by author Bryan P. Shumaker for his son, could withstand wear and tear better than its commercial counterparts. For one thing, its wooden composition kept the structure from rusting over. The geodesic shape also gave the playhouse enough strength to survive numerous playtimes. Construction was relatively simple, as Shumaker’s playhouse required just two primary materials: Wolmanized wood for the panels and and Starplate connectors to connect joints on the frame.

In 1987, writer V. Elaine Gilmore traveled to Melbourne, Florida, so that she could experience life in a geodesic dome house. Unlike the wooden dome houses we covered previously, this one was made of concrete and flame-retardant polystyrene. Houses made of these materials were reportedly resistant to rot, termites, and undesirable temperatures. Home owner and American Ingenuity president Micheal Busick explained that foam retained the house’s heat during the winter, and its coolness during the summer (a high priority for any Floridian). Foam was easy to cut, hard to penetrate, and relatively inexpensive. American Ingenuity built their homes for between $32 and $38 per square foot, which is about what you would pay for a conventional house of the same size.

All right, these dome homes are more igloo-shaped than geodesic, but we couldn’t resist including a dome cluster in this gallery. Michael E. Jantzen’s modular dome home, which was made out of silo materials, consisted of four units. Two held bedrooms, one held the living room, and another held the kitchen and dining area. Jantzen told us that his dome houses were easily expandable. You could grow and shrink the house (by building or storing away units) depending on how many people resided there at a given time.