Business-to-business sales are an opaque world, driven by profit, bounded by costs, and full of unknown, confounding variables. CaliberMind, a two-year-old company founded by two former Israeli intelligence officers and an NSA data scientist, exists to help businesses seal deals with other businesses better.

To do that, the company looks at public information or shared conversations, and then profiles the people making the buying decision, including the group dynamics of the buying team. The end result, CaliberMind CEO Raviv Turner promises, is a sale cycle that’s up to “20 to 30 percent shorter.”

Let’s step back for a minute: this is not a service that most people will ever see, really. Unlike consumer transactions, where credit cards are matched with buyer history so Amazon knows to recommend the recent humidifier-buyer an endless array of other humidifiers, businesses purchasing goods or services valued at more than $100,000 from other businesses is a relatively rare event, and one not linked to easily traceable buyer information. So if a company wants to make sure that it is not just selling what the other business wants, but that the people at at company will buy it, what’s the answer?

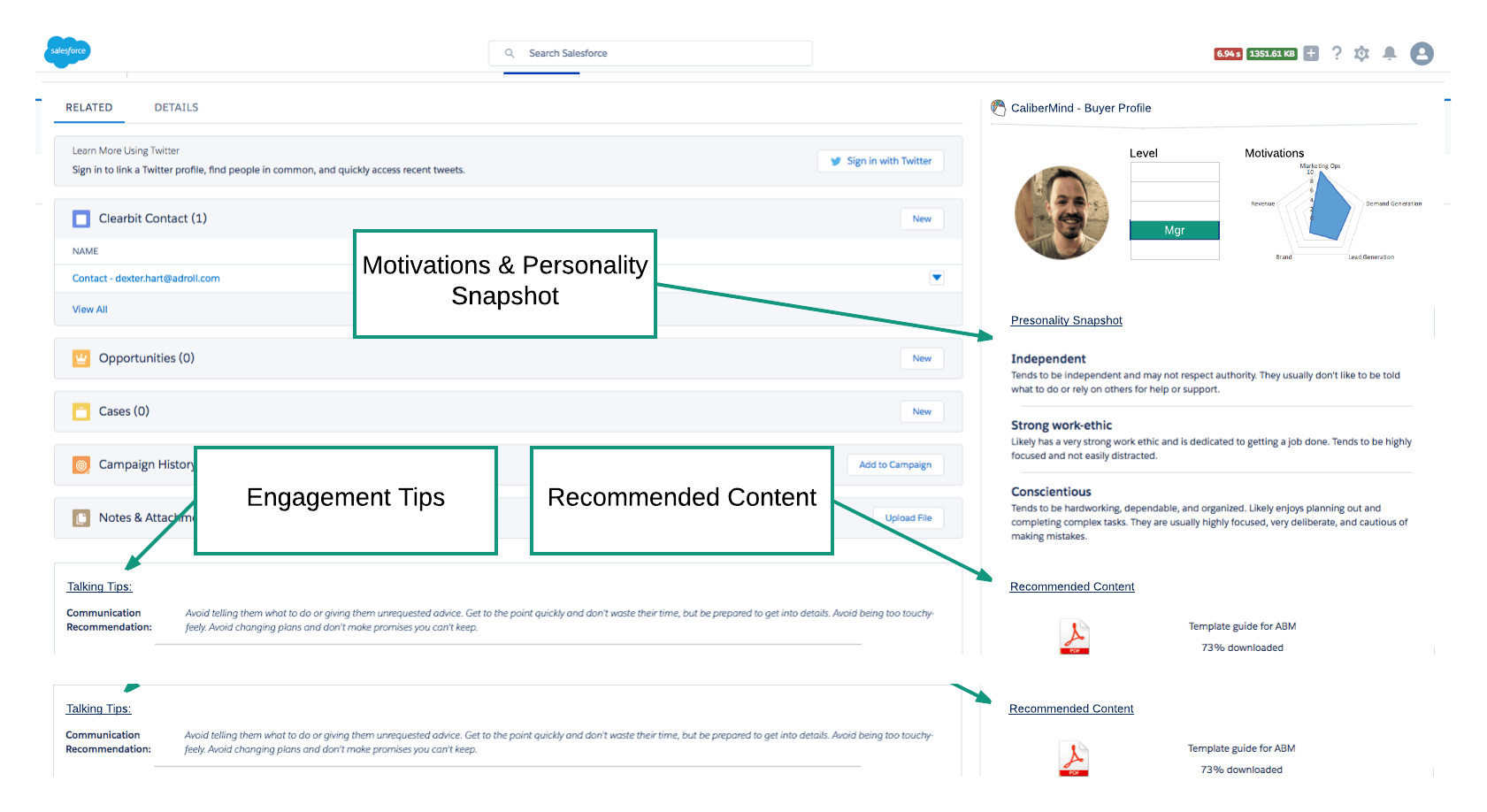

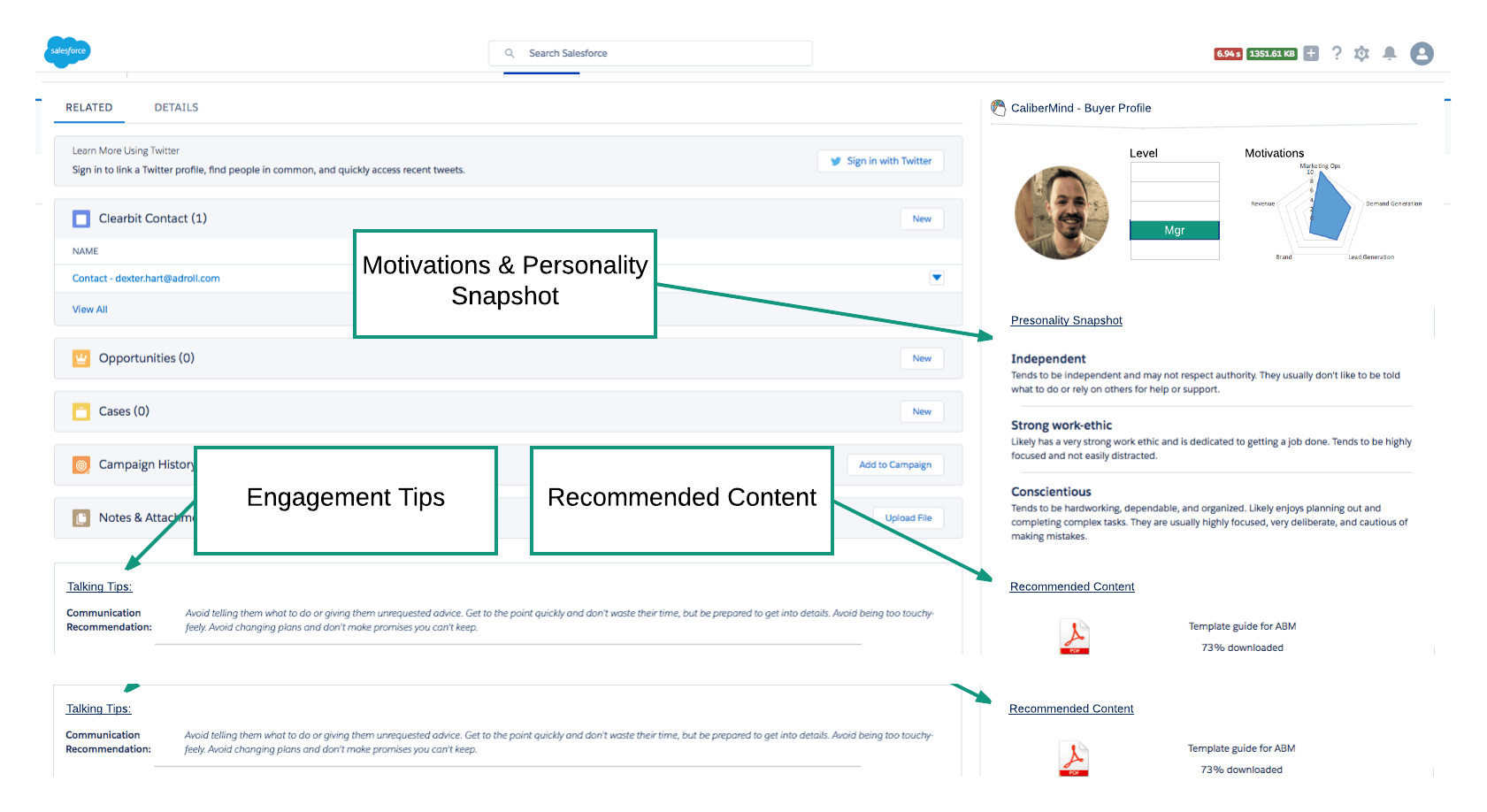

Turner’s company focuses on the people in the buying decision. Specifically, they focus on the psychographics of buyers, or the interests of the person making the buying decision. Psychographics have been around for a long time, and they’re part of why a successful marketing professional may know to reach out to a reporter through a Twitter direct message instead of another email, because said reporter is perhaps more interested in keeping up with news-by-the-minute than completing old correspondence. What CaliberMind does is look for the psychographics of a team of people, and try to figure out not just the best marketing approach for each team member, but to find who on that team is likely to have the most influence over a sale.

According to Turner, CaliberMind mostly works with public information, perhaps pulled from LinkedIn profiles or public Facebook accounts, and sometimes supplemented by calls recorded with the consent of the listener. CaliberMind can build psychographic profiles with just 100 words from the person. From there, the tool recommends ways to convince the buyer

“If I know that for example, Kelsey is the analytic, revenue-driven CEO,” Turner said, in a perhaps-comical example, “he has probably the authority to sign off on the deal, but I cannot win Kelsey over with an invite to a webinar or a video. Kelsey needs the link to the online calculator, maybe a spreadsheet, to wry analyses or a case study with metrics about the competition. The idea is that we can power the marketing and the sales reps with personality data and psychographic, that they can optimize the communication.”

So what does it look like when CaliberMind actually profiles a person, instead of just guessing at it? I asked Turner to analyze a writing sample of mine (this story, specifically). Within hours, I got a response back. I was profiled on 60 metrics. The combined picture, according to CaliberMind, is that I am independent, easy-going, and introverted, which is probably as fair a description as any, but what I really wanted was the communication recommendation: “Try to avoid telling them what to do. Avoid placing tight constraints on them, such as short timelines. Do your best to focus on the subject at hand and try not to get too personal.” That description, in fairness, might apply equally well to any number of journalists, and the words it was based on were pulled from an editing and published story, instead of a purely personal blog post, but I was reasonably impressed.

Figuring out how to talk to a reporter isn’t really the kind of problem that CaliberMind aims to address. For one, reporters are pretty straightforward in the kind of information they want, and for another, they’re at best rarely in charge of six-figure purchases. To court the kind of people involved in a company’s major buying decision, Turner boasts of a kind of “next-best” recommendation tool in CaliberMind, like how Netflix recommends Die Hard to someone that just watched Face/Off.

“Caliber can recommend the next-best should be a phone call, because this person is warm and friendly and they like to talk, versus a cold email,” Turner says. “So Caliber can set up this call and it can also analyze this call, and notice that the person actually is very price sensitive, so next-best would be sending them the pricing sheet, how yours compares as far as value goes to your competition. Then they open a spreadsheet, and then maybe the next is a live demo or a call with an analyst.”

This is a months-, sometimes years-long process, an elaborate series of negotiations for companies to both get to yes and feel like they’re getting a good deal. And as part of that, CaliberMind aims at understanding entire teams, and the dynamic within them, rather than just convincing a single person. In the 1980s, executives looking for an advantage turned to Sun Tzu’s Art of War, the venerable tome of broadly applicable insight from the ancient Chinese theorist. Rather than relying on ancient wisdom, Turner sees the work of CaliberMind as a fundamentally modern problem, one whose complexity can only be solved my machines.

“With this kind of problem, I don’t know if it’s possible for a human to solve this kind of problem,” says Turner. “You’re talking about terabytes of data and sales of cycles that can last anywhere from 3 months to 2 years. Think about all the sales conversations, all the emails, all the content downloads and all the actions stacking in a deal like that, and then multiple that by 5 to 15 people involved in the deal, and now you see that that’s a machine problem.”

So where does the intelligence background fit into all of this? Mapping the motivations, interests, and personalities of people from what they say publicly online and turning it into psychographic profiles isn’t just of interest to marketers.

“Some of this is based on algorithms government agents to do,” Turner said, “but instead of using it for counter-terrorism or extremists, we had to adapt it to the world of complex enterprise sales.”

Turner didn’t go further into the government work he and his partners used to do, but he did offer later that, anticipating sensitivity to privacy concerns, “we’re only working with public data, we also apply to the European new security standard Privacy Shield.” That standard, launched by the European Commission in July, requires certain protections from companies that handle data in the United States, as well as individual right protections.

So the data that CaliberMind looks at is publicly available or surrendered voluntarily, like when participants on a phone call agree to recording that call.

“In my personal life,” Turner joked at the end of our call, “I think I gave up on privacy for a better technical experience a long time ago.” With CaliberMind, companies can place a bet that work emails, phone calls, and LinkedIn profiles, are more valuable not just as communication, but as profiled data, all in the service of getting to yes.