3-D printing has been touted as the most amazing thing to happen to manufacturing since the assembly line. The idea is that, someday, every home could be a mini-factory, downloading CAD templates online and printing off eyeglasses, coffee mugs, shoes, and whatever else a household might need. The problem is that right now most 3-D printers can only print the equivalent of plastic toys—plus a few guns, pizzas, and body parts here and there.

“In the world of 3-D printing, the big push is to try to print with multiple materials at once,” says mechanical engineer Michael McAlpine. “What they really mean, usually, is printing in two different-colored plastics.”

McAlpine and his colleagues at Princeton University, however, have gone far beyond two-toned action figures. They mixed and matched five different materials into the first fully 3-D printed LED lights. Although other teams previously claimed the honor, McAlpine says those weren’t the real thing. “They print a breadboard of electronics, then plug regular LEDs into it.”

More specifically, the LEDs (or light-emitting diodes) that the Princeton team created are called quantum dot LEDs. They’re a lot like the LEDs that are built into television and cellphone screens, but there’s some hope that QD LEDs could be more energy efficient.

To make the LEDs from scratch, the researchers had to build a custom 3-D printer. They spent about six months and between $10,000 and $20,000 assembling the printer.

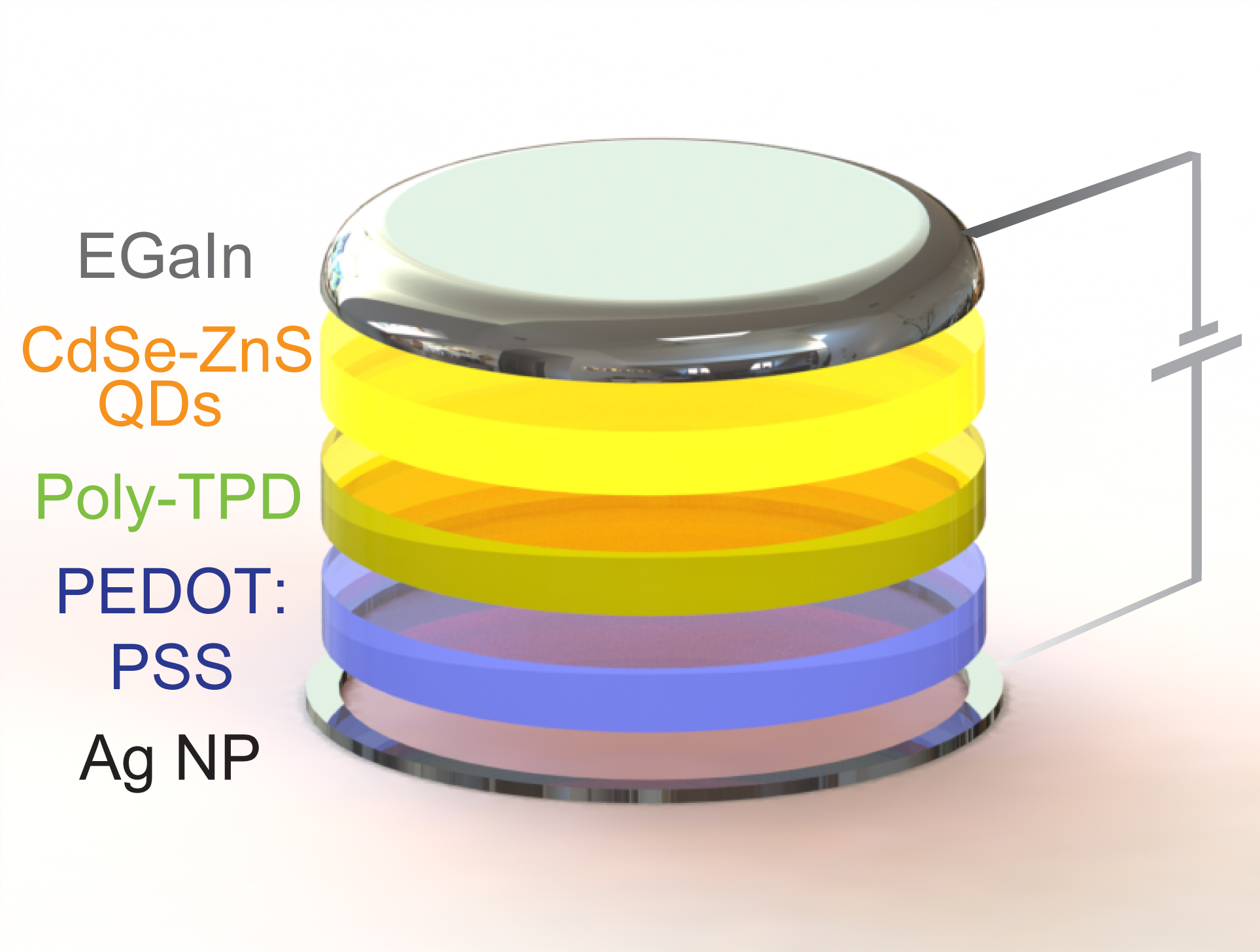

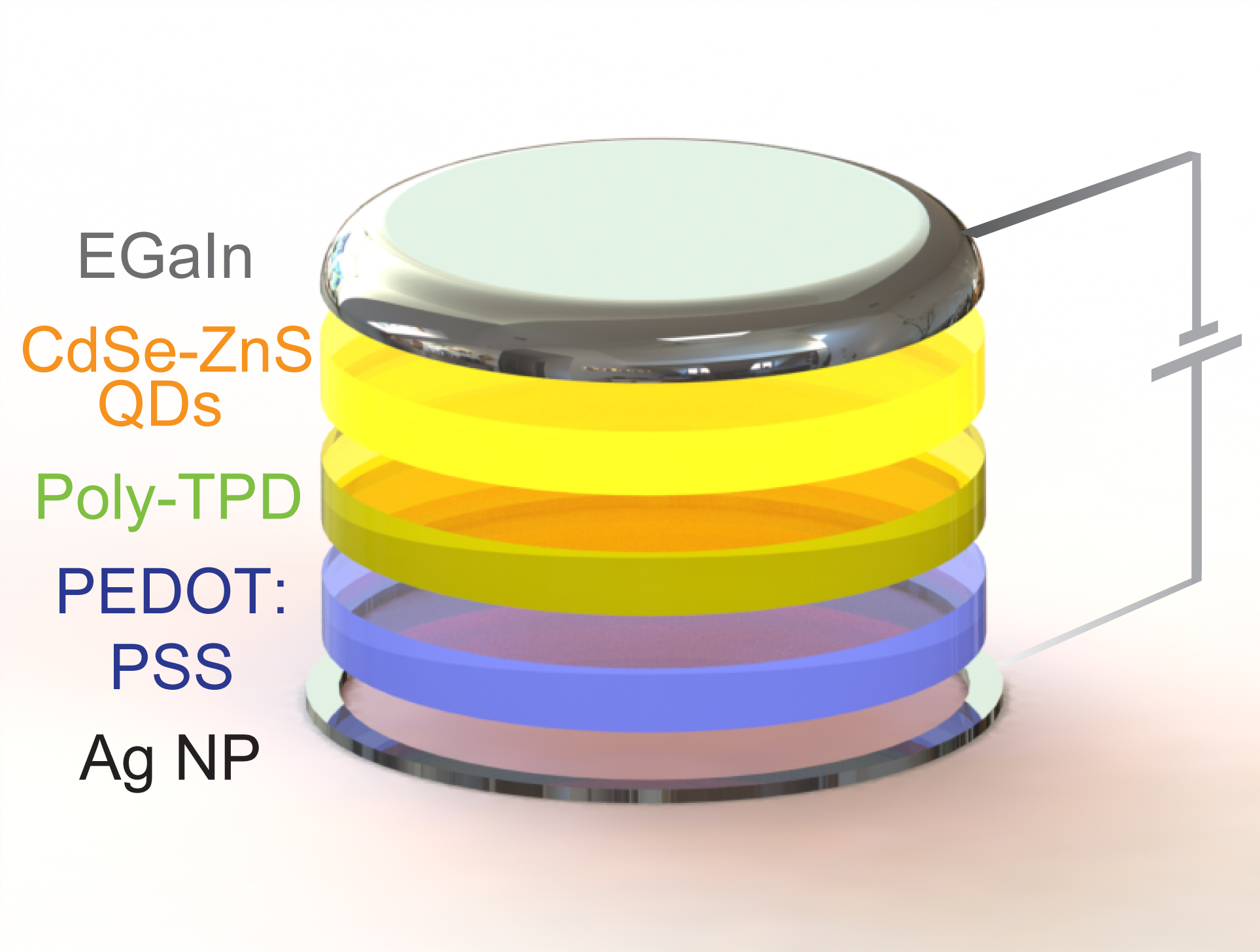

The printed LEDs have five layers. On the bottom, a metal ring made of silver nanoparticles acts as a metal contact to an electrical circuit. On top of that are two polymer layers (both with really long chemical names) which together supply and shuttle electrical current to the next layer. That contains the quantum dots. The quantum dots are made of cadmium selenide nanoparticles wrapped in a zinc sulfide shell. As the electrons bump into these quantum dots, they emit orange or green light. The light is topped of with a cathode layer made of eutectic gallium indium, through which the electrons flow out of the LED.

In addition to combining metals and polymers, some of the materials were hydrophilic (water-loving) while others were hydrophobic (water-repelling); some were liquids while others were solids. McAlpine says it’s the largest number of distinct material classes that have been 3-D printed into one object.

The printed LEDs performed on par with the kinds of LEDs that are used in iPhone screens, though they didn’t come close to beating the really fancy LEDs that are out there. But by controlling thickness and uniformity of the quantum dots, and by experimenting with different ink formulations, the performance of the printed LEDs could get better. Perhaps one day, if 3-D printers get cheaper, people could incorporate something like this into homemade TVs and iPhones.

But McAlpine imagines more exciting possibilities. “The conventional microelectronics industry is really good at making 2-D electronic gadgets,” he says. “With TVs and phones, the screen is flat. But what 3-D printing gives you is a third dimension, and that could be used for things that people haven’t imagined yet, like 3-D structures that could be used in the body.”

Up next, McAlpine’s team (who made a 3-D printed bionic ear last year, by the way), wants to try printing transistors, so that their 3-D printed gadgets could have the kind of functionality you might find in a computer chip.