We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

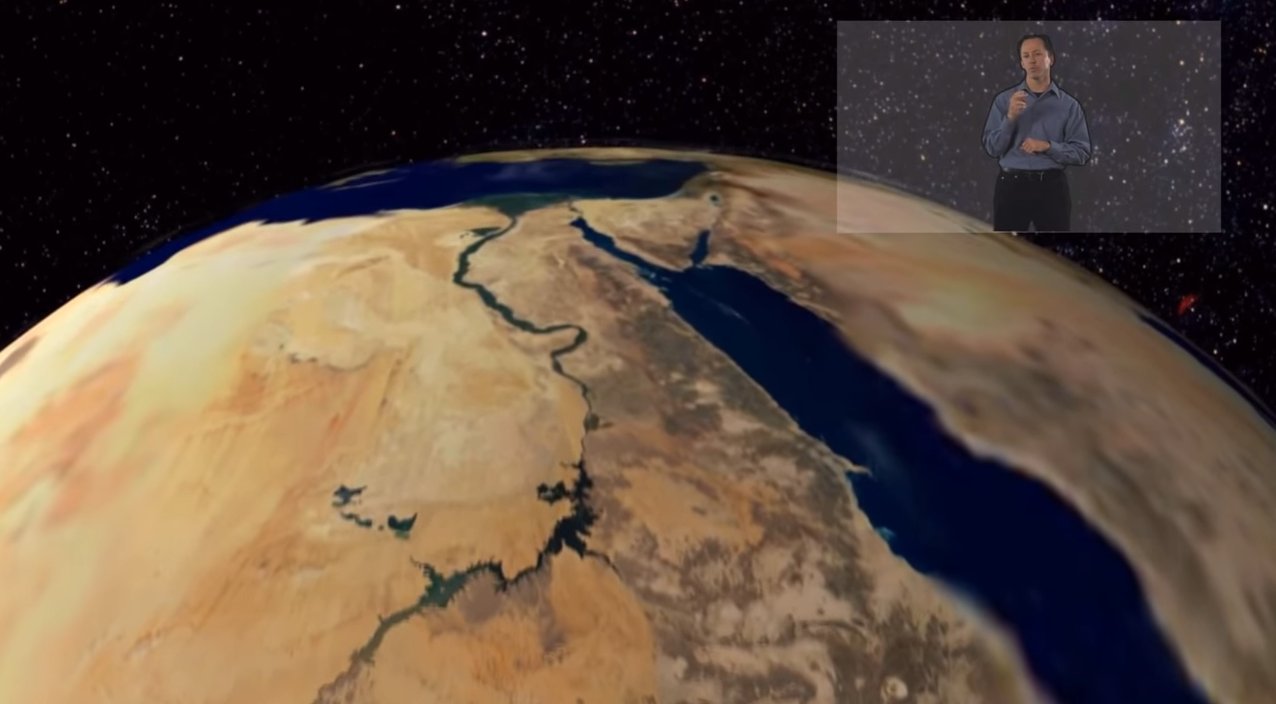

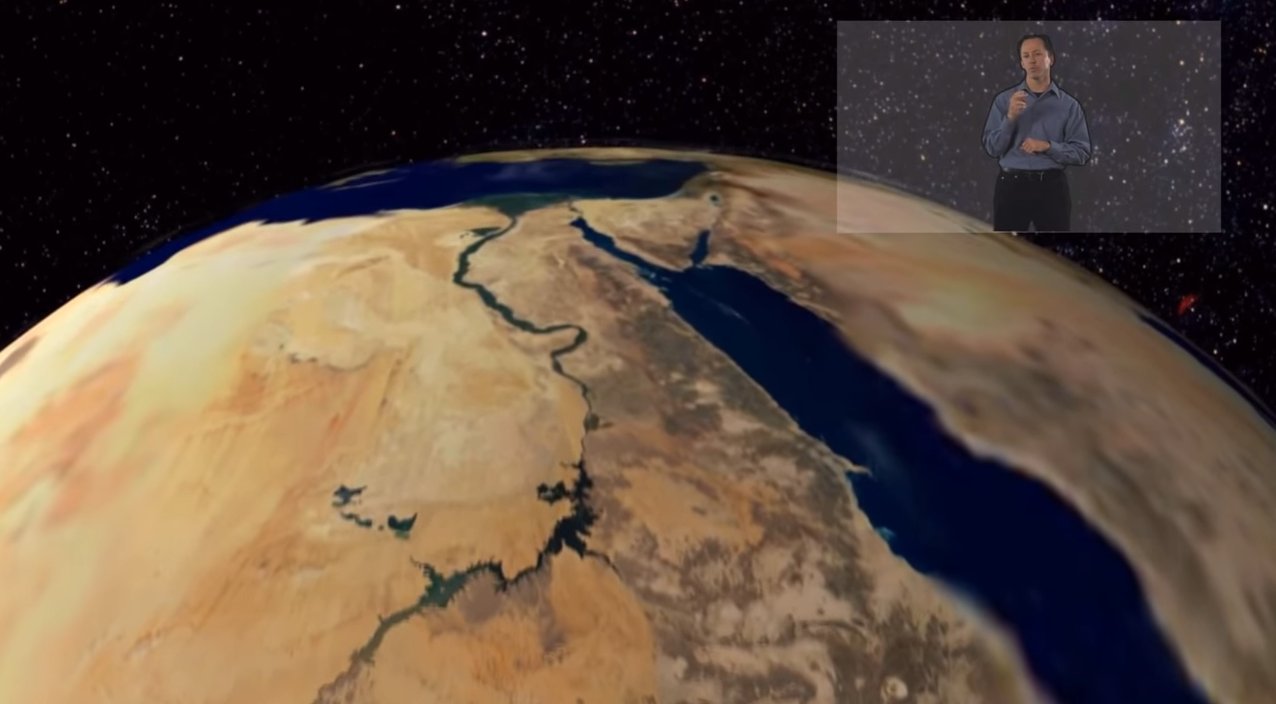

About seven years ago, a summer camp for deaf kids visited the planetarium at Brigham Young University in Utah. An American Sign Language interpreter sat on the floor with the kids to translate the show’s narration. The kids would lean back to watch the stars on the domed ceiling of the planetarium, but then they would have to pause and shift their attention down to catch the narration. Up, down, up, down. The show took nearly twice as long as it does with spoken narration only, and it wasn’t exactly the magical, transporting experience planetarium shows can be.

“I have a cousin who’s deaf, so I actually thought through this ahead of time,” Jeannette Lawler, the planetarium’s director, tells Popular Science. Still, even with all her planning, “I was really dissatisfied with the quality of the show I presented.”

So, she began talking with other planetarium directors. Some told her they used captions for deaf visitors. That won’t work for kids who are just learning to read, she pointed out. Then the director at another Utah planetarium thought of using head-up displays that could beam an ASL narration right in front of the kids’ eyes. It was a prescient notion; it would be years before Google announced its Glass project. But Lawler recognized a good idea when she saw one. She recruited BYU computer scientist Michael Jones to develop software to go with head-mounted displays and launched a research program, bringing kids in to test Jones’ apps, as well as different devices. They’ve tested everything from rugged headsets originally designed for soldiers to Google Glass.

Now, Jones and students in his lab have designed their first planetarium app. They’ve gathered kids’ responses to wearing head mounted displays, which they’ll present at a conference in June. They also hope to recruit teachers who teach deaf kids to try head-up displays in their classrooms this fall. Jones has even come up with an idea for a computer vision-based head-up display app that could help deaf kids learning to read. The app would recognize when kids point to an unfamiliar word in a book, then pull up a video of an ASL speaker giving a definition.

“Imagine a deaf surgeon using the glasses to read/understand what others around him are saying while he’s performing the surgery.”

In the future, head-mounted displays could help deaf students in everything from English class to biology lab. Crucially, they eliminate the need to look back and forth between an interpreter and a lab demo or diagrams on the blackboard.

Tyler Foulger, a BYU undergraduate who helped translate for Jones and his focus-group kids, has run into this problem before. “Last year, I took a molecular biology lab with an ASL interpreter. When the instructor was explaining or demonstrating how to perform a certain task, I had to continually shift my attention from my interpreter to the instructor. This caused me to miss out on some of the important things that were said,” he says. I don’t know ASL, so Foulger and I talked on Google chat. “I was often behind,” he says. “I believe the glasses we’re developing will help combat that problem.”

Foulger, who plans to apply to medical school, has more ambitious ideas for the glasses, too. “Imagine a deaf surgeon using the glasses to read/understand what others around him are saying while he’s performing the surgery.”

For now, the Jones and his colleagues use pre-recorded videos of ASL speakers to narrate. In the future, Jones envisions making apps like this that could stream video from an interpreter to display wearers. That’s what would be needed for a surgeon, or even just for teachers who don’t want to have to pre-record everything they want to say. Jones and his students have set up a proof of concept of this streaming idea. For now, their prototype requires a hookup to a laptop.

Does this mean we’ll see a bunch of Google Glasses on kids in 2020? Not quite. So far, Lawler and Jones’ research has found that no device on the market today is exactly what deaf kids need. Some are too big and heavy for kids to use. Google Glass is light and comfortable, but it’s not perfect, either. For one, it shows things to the side of the user’s field of view. Focus groups say they prefer to see their interpreter right in the middle of their field of vision. Glass also works primarily with voice commands, a no-go for the majority of the deaf community.

Jones’ lab has just starting designing their own glasses for kids. But maybe they won’t have to. “There’s new stuff coming out all the time,” Jones says. “With a little patience, somebody else might solve the problem for us.”