Dutch designer Pauline van Dongen argues fashion is in desperate need of a revolution. In her eyes, the industry is so concerned with producing stock that no one is making enough time for rethinking the textile production process. That’s why van Dongen has turned to emerging technologies for her clothing’s bold designs and atypical manufacturing methods.

Van Dongen recently turned to 3D printing to see if it could lead to clothing that’s more body-focused and responsive to how a person moves. She detailed her experimentation in 3D-printed fashion at South by Southwest this year, noting there’s still more to do before we all see 3D-printed garments on clothing racks. But she hopes her work will inspire other designers to see what’s possible.

Explore a gallery of her newest concept below. (Video credit: Nicolas Cambier)

Popular Science is at South by Southwest in Austin, Texas, bringing you the latest technology and culture news. Follow our complete coverage at popsci.com/sxsw.

Sleeve Design

Van Dongen’s first foray into 3D-printed fashion was relatively simple: She made a sleeve. But she wanted the garment to function as more than just a cover, so she tried to give it auxetic behavior, or make it thicken when stretched. With an Objet Connex multi-material printer, van Dongen printed this geometric design–made up of rhomboid-shaped elements–in flexible, rubber-like materials and solid plastics.

Body-Activated Sleeve

In collaboration with Paola Tognazzi and Ralph Zoontjens, Van Dongen’s idea for the sleeve was to materialize a person’s movements, so she equipped sensors to people’s arms to map out their motions. Then, using software called Grasshopper, she tinkered with the pattern on a computer to see how it might respond when worn. The result is a garment that acts like a visual feedback mechanism for various gestures, changing its shape based on how you move. As a person lowers his or her arm, for example, elements of the sleeve either expand or contract (as seen in the photo here).

Springing To Life

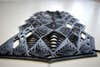

Van Dongen’s second 3D-printing project, Ruff, was made in collaboration with architect Behnaz Farahi. They wanted to use 3D-printing technologies to create a dynamic, flexible shape that moved around the body. However, they learned the materials often used for 3D printing are rigid and easily broken. To counteract this, van Dongen and Farahi experimented by printing various spring-like plastic shapes. These structures proved to be much more durable and pliable.

Responsive Wearable

Working with 3D Systems’ printing facilities at Will.i.am’s studio in Los Angeles, van Dongen and Farahi ultimately created this 3D-printed “responsive wearable.” The spring structures undulate around the body, giving an aesthetic of deep sea corals moving in the ocean. According to van Dongen, the name Ruff also refers to the ruff folded collars, which western Europeans commonly wore in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Science In Motion

To activate the 3D-printed springs’ movements, van Dongen fitted them with wires made of nitinol–aka nickel titanium. Nitinol exhibits the unique property of shape memory. At one temperature, the metal deforms, but when heated back to its “transformation temperature,” nitinol goes back to its original, undeformed shape. By fitting the nitinol spring with small electric cables, van Dongen was able to adjust its temperature, prompting the wire to expand and contract. The effect was a “breathing like, organic entity” that seemed to crawl over the wearer’s body.