For the past hundred years, we’ve been dreaming about flying cars. Transportation has come so far since the automobile’s invention that flying cars seem like a natural part of what life should be by now. Who hasn’t suffered rush hour traffic without imagining one’s vehicle zipping above the congested highways? Flying cars would be fun to drive. Flying cars would eliminate the hassle of finding a ride to and from the airport. But, unhappily, flying cars have yet to achieve ubiquity.

It’s not as if the automobile industry has lacked viable candidates for a mainstream f.c. We perused our archives to unearth a number of flying cars that we’d love to take for a spin.

Click to launch the photo gallery.

In between the Wright brothers’ flight at Kitty Hawk and the rise of Henry Ford’s automobile factories, the first part of the 20th century became a milestone era in transportation. In 1917, aviation heavyweight Glenn Curtiss presented his Model T Ford-like Autoplane at the Pan-American Aeronautical Exposition held in New York. Although the vehicle only managed a few hops, Curtiss still earned a reputation as the father of the flying car. Then, in 1924, Captain Eddie Rickenbacker assured us that flying autos would become commonplace within the next two decades. So what happened?

Every decade thereafter saw the invention of a flying car. Many vehicles were labeled with catchy portmanteaus, like the “Airphibian” and “Aerobile,” and almost all were touted as the next big thing in personal transportation.

Despite their initial optimism, inventors and transportation companies alike balked at the cost of mass-producing flying cars. Perfecting the technology would require time and money, as early prototypes were so bulky that they couldn’t perform at optimal speed in either the air or on ground. Testing often proved dangerous, as people found when Henry Smolinksi died while test-flying his AVE Mizar. Factor in the need for wider roads, revised air traffic laws, and individual pilots’ licenses, and you can see why it might take longer than expected for roadable aircraft to take flight.

If we’re lucky, we’ll live to pimp our stratosphere-skimming rides with propellers and detachable wings. In the meantime, click through our gallery to see the winged tanks, flying jeeps, and other weirdly wonderful vehicles that never quite made it off the ground.

Eddie Rickenbacker’s Flying Autos: July 1924

We aren’t the only ones who are impatient to graduate from the streets to the skies. Celebrated pilot Eddie Rickenbacker predicted that people would zip around in flying cars by the year 1944. The machine would be equipped with collapsible wings spanning 25 feet, a front-end propeller, and even pontoons for water travel. The “flying roadster’s” body would be more streamlined to reduce weight, and its engine would be light, small, and supercharged. To reduce accidents and air traffic, cities would construct giant landing fields out of building rooftops connected by bridges. After landing, the flying cars would take a special elevator down to street level, where they would drive around like regular land-based vehicles. Read the full story in “Flying Autos in 20 Years”

Curtiss Autoplane: July 1927

Renowned aviator Glenn Curtiss, rival of the Wright Brothers and a founder of the U.S. aircraft industry, could also be called the father of flying cars. In 1917, he unveiled the Curtiss Autoplane, which is widely considered the first of its kind. The aluminum autoplane had a Model T Ford-like body, four wheels, a 40-feet wingspan, and a giant 4-blade propeller mounted in the back. Although the autoplane only managed a few hops, people lauded Curtiss’ “aerial limousine” as the forerunner for personal vehicles to come. Read the full story in “Glenn Curtiss Sees a Vision of Aviation’s Future”

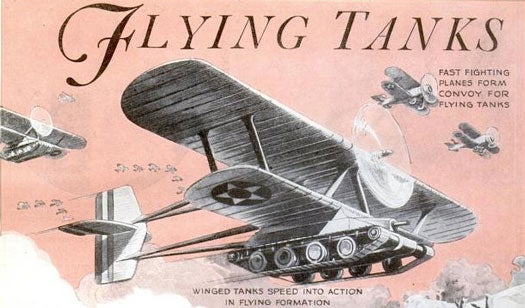

Flying Tanks: July 1932

In response to the horrors of trench warfare, inventors raced to develop flying tanks that could land on the battlefield and be ready for immediate combat. American engineer Walter J. Christie envisioned a four-ton armored vehicle equipped with a 1,000-horsepower motor, a propeller, and detachable wings. Each tank would be commanded by two men. Upon landing, the driver would pull a single lever, releasing the wings, and advance into battle. Meanwhile, the Soviet Air Force designed their own winged tanks, like the Antonov A-40, which was essentially a T-60 light tank with large biplane wings and a twin tail attached. Despite the efforts of engineers, flying tanks never really caught on, so further efforts were scrapped and largely forgotten. Read the full story in “Flying Tanks….War’s Deadliest Weapon”

Waterman Arrowplane: May 1937

Based on the picture and description, we’ve concluded that this unnamed vehicle is Waldo Waterman’s Arrowplane, a three-wheeled roadable monoplane inspired by Glenn Curtiss’ autoplane. The Arrowplane, also known as the Arrowbile, had an engine and propeller in the back. Two decades later, Waterman unveiled the Aerobile as an upgrade to the Arrowplane. Five Aerobiles were built, and two flights from Santa Monica to Ohio completed, but nobody bought them. Eventually, one of the Aerobiles ended up on display at the Smithsonian, and today, the vehicle is known as one of Time Magazine’s 50 Worst Cars of All Time. Read the full story in “Plane Sheds Wings to Run on Ground”

Windmill Autoplane: June 1935

While there isn’t much written about this machine, its autogyro-like design helps it stand out from its competitors. In flight, the machine would function like any other autogyro. Upon landing, however, its blades would fold downward, allowing the machine to drive along the highway. Read the full story in “New Craft Combines Auto and Plane”

Aerobile: December 1940

This torpedo-shaped vehicle, called the “Aerobile,” was manufactured by an unnamed inventor from Dayton, Ohio. In theory, a pusher propeller would drive the plane during flight, and we say “in theory” because no one actually attempted to fly this thing. At best, the Aerobile was one of the more aesthetically pleasing prototypes released during the mid-20th century. Read the full story in “Detachable Wings Turn Three-Wheeled Car into a Plane”

Post-War Family Car: November 1942

Although the war was far from over in 1942, we couldn’t help imagining how awesome life would be after the Allies’ inevitable victory. Discoveries made during the period of wartime research would revolutionize the transportation industries. Soldiers arriving home from the war would likely prefer private air travel over driving. The demand would foster a relationship between the automobile and aviation industries, which would then cooperate to make light planes as ubiquitous as family cars. Flight strips would run parallel to roads, while gas stations would be redesigned to accommodate hangar spaces. The picture at left, called the Aerial Family Car, may resemble a Ford Flivver plane more than a flying auto, but its high-lift flaps would allow for steep takeoffs from suburban front yards. Read the full story in “War’s End Will Bring a Better Life”

The Plane You’ll Fly After the War: March 1945

In the fall of 1944, we ran a contest asking readers to submit designs for their ideal postwar private planes. Much to our surprise, analysis of the 3,345 entries revealed that only 10 percent of people surveyed wanted roadable aircraft. The vast majority of people preferred low-wing monoplanes or planes with pusher props, the reason being that they favored safety over novelty. The tailless design pictured left was submitted by Ray Ring, of Framingham, Mass. Only about 14 percent of the people who designed flying cars preferred foldable wings over detachable ones. Read the full story in “These are the Planes You’ll Fly After the War”

ConvAirCar: April 1946

After the War, Convair commissioned a flying car suitable for everyday use. With Tommy Thompson’s help, Ted Hall developed the three-wheel Convair Model 116, a two-seater with detachable monoplane wings, tail, booms and propeller. Just three months after we published this article, Model 116 made its first flight and completed 66 others. Hall subsequently tweaked the Model 116 to give it a more powerful engine and refined body, thus producing the Model 118, or the infamous ConVairCar. Although Convair planned to produce 160,000 Model 118’s, the project was shut down after a failed one-hour demonstration flight ruined the prototype and injured its pilot. Read the full story in “Drive Right Up”

The Airphibian: April 1946

While developing his Airphibian, famed American inventor Robert E. Fulton took a different route than most: instead of altering an automobile for the air, he adapted an airplane for the road. Fulton’s idea for a flying car came from his frustration at having to find ground transportation after landing at an airport. Like us, he figured it would be much more convenient to land wherever you wanted to. The end product could fly 12,000 feet at 110 mph and drive 56 mph on ground. He boasted that the machine’s detachable wings could be disassembled in five minutes by just one man. Although the Airphibian was the first flying car to receive certification from the Civil Aeronautics Administration (predecessor of the FAA), financial difficulties forced Fulton to cancel the project before the Airphibians could go into mass production. Read the full story in “What It’s Like to Fly a Car”

Flying Jeep: May 1958

Although the Flying Jeep, or Piasecki Airgeep, isn’t what you’d typically imagine upon hearing the words “flying car,” this VTOL could both hover close to the ground and fly several thousand feet above it. Unlike the other machines we’ve covered so already, the Airgeep’s lack of wings allowed it to fly between buildings, trees, and other tight spaces. The Airgeep II, completed in 1962, was fitted with an ejection seat for pilots, two Artouste engines, and a tricycle undercarriage for improved travel on land. Despite its versatility, the Airgeep failed to make a lasting impression and was thus eclipsed by research into more conventional aircraft. Read the full story in “Army Jeep Turns to Skyriding”