Octopuses and their cephalopod cousins have long fascinated biologists with their seemingly supernatural shapeshifting. The cephalopods rapidly change color and texture, blending into their surroundings and evading predators. This natural camouflage is a remarkable bit of biology that engineers have tried to replicate, albeit with limited success. But that may be changing.

Researchers at Penn State say they’ve developed a new hydrogel material inspired by octopus skin that can encode images directly into its structure. The imprinted images then disappear and reappear when the skin is exposed to subtle changes in temperature or a surrounding solvent. The result is a “4D” synthetic smart skin capable of revealing hidden images and shifting surface patterns.

To demonstrate the technology, the team encoded a black-and-white image of Leonardo Da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” into the material. At room temperature, the image is essentially invisible. However, when heat is applied the hidden contrast sharpens until the image becomes clear. Though still early in development, the material could lay the foundation for synthetic adaptive camouflage, with potential military applications and beyond. The findings were published this week in the journal Nature Communications.

It’s an impressive engineering feat that also highlights the elegant complexity nature has refined through millions of years of evolution. Even with all our resources and combined brian power, humans still can’t best nature’s innate artistry.

How octopuses hide

Scientists are starting to really understand the complexity of octopus brains and their unique capacity for problem-solving. When it comes to shapeshifting though, the process appears to be more instinctual than deliberate.

Biologically, cephalopods rely on specialized neuromuscular organs called chromatophores to perform their evolutionary magic trick. The chromatophores expand and contract in response to neural signals triggered by environmental cues. They also use muscular hydrostats to rapidly alter the texture of their skin. Together, these features give octopuses an extraordinary dynamic range of appearance, allowing them to seamlessly blend into their surroundings.

“This intricate system of nerves and muscles grants soft-bodied organisms the remarkable ability to simultaneously alter their optical appearance, surface texture, and shape,” the team on this new study writes.

Printing a ‘newspaper’ on skin

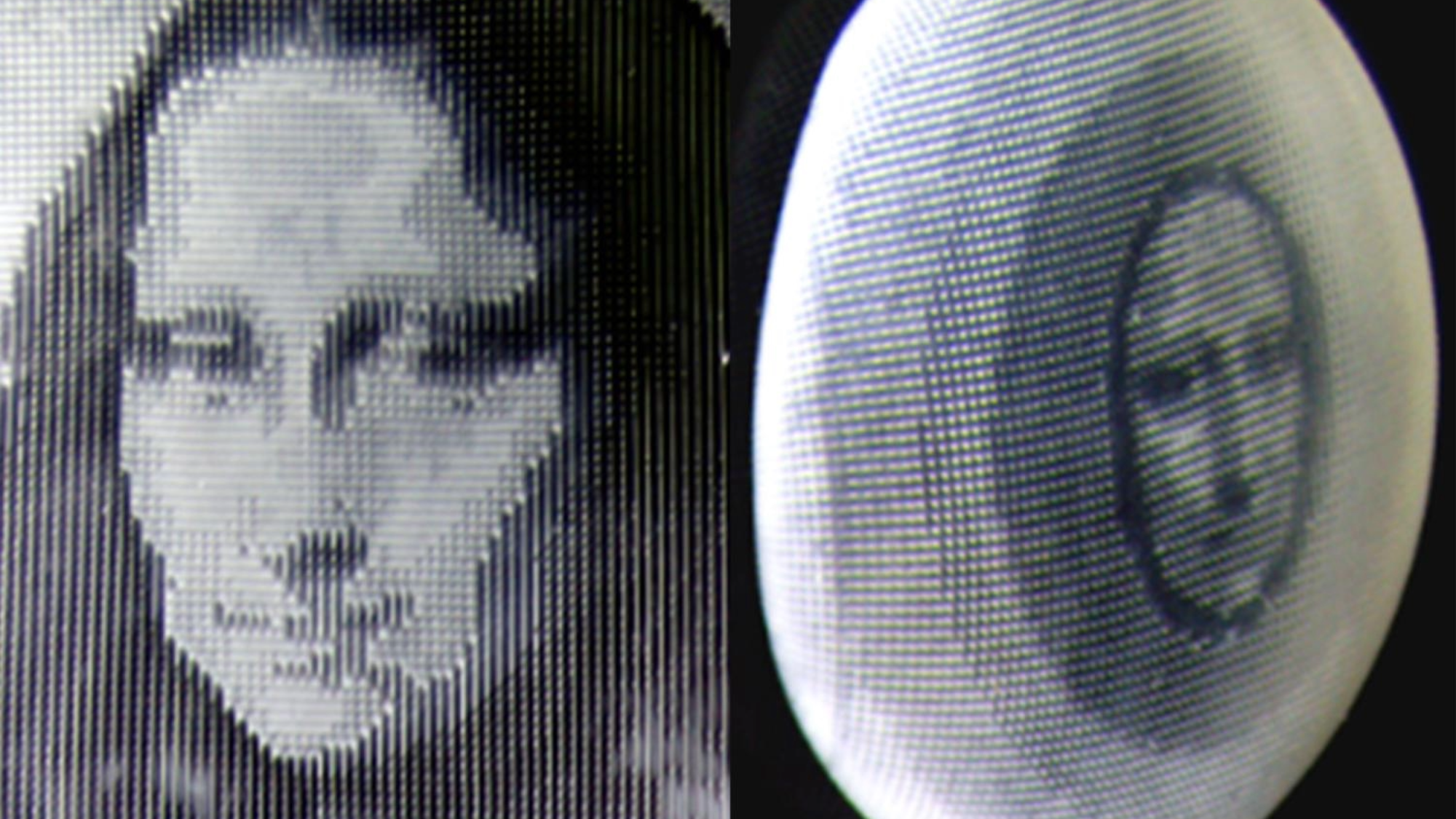

To try and replicate how octopuses camouflage and shape shift in a lab, the Penn State team needed a way to alter both appearance and shape using a single, soft synthetic material. They started by 3D-printing a hydrogel that would serve as their canvas. Using a process called halftone-encoded printing, the researchers first translated an image into a binary grid of pixels, where different patterns of 1s and 0s corresponded to regions of the material with distinct physical properties. Much like newspaper printing, the density and distribution of these pixels create the illusion of light and dark areas.

Once the image was converted into a binary pattern, the team encoded it directly into the hydrogel using controlled UV light during the printing process. In other words, the image was “seared” directly onto the hydrogel canvas. Rather than adding ink or pigment like a tattoo, the UV exposure programmed subtle differences into the material’s internal structure. Under normal conditions, these differences are invisible to the naked eye.

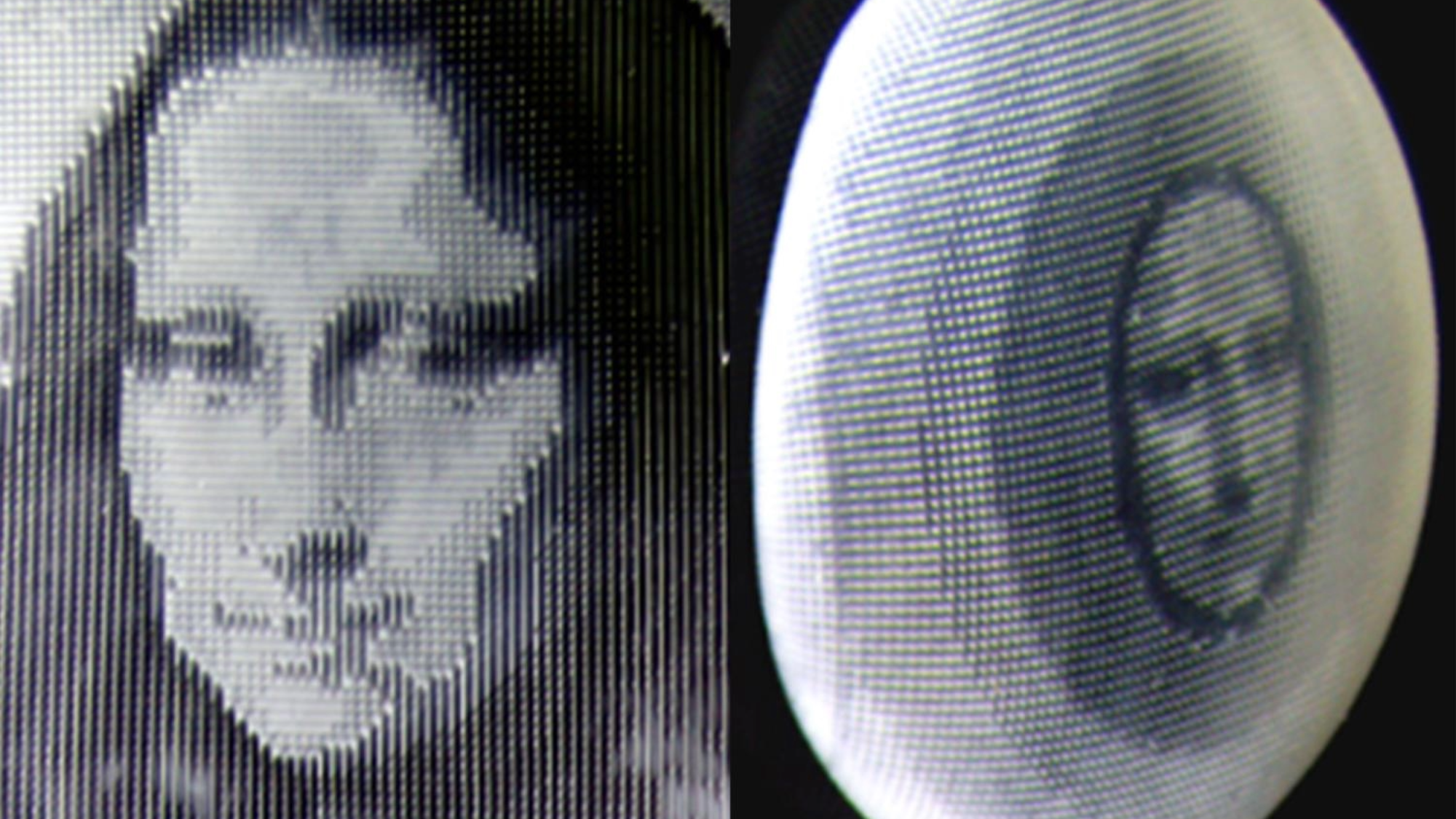

But when the material is heated up, the areas corresponding to the 0 and 1 patterns respond differently, gradually increasing their visual contrast. The previously hidden image then emerges as the material reacts to its environment. The process is somewhat similar to how invisible ink is exposed when a revealing solution or special light is applied. The researchers describe this as a form of 4D printing because it takes a three dimensional object and alters its appearance over time via exposure to external stimuli. They were also able to demonstrate the same effect by changing the surrounding solvent, which caused the hidden image to reappear.

“We’re printing instructions into the material,” Penn State industrial engineer and study co-author Hongtao Sun said in a Penn State blog post. “Those instructions tell the skin how to react when something changes around it.”

To demonstrate this effect, they first encoded the letters “PSU” into the hydrogel film. After altering the film’s temperature, the letters revealed themselves. Upping the difficulty, they then repeated the process with a grayscale image of the “Mona Lisa.” In theory, they say the same approach could work with any image. It simply needs to be converted into a binary pattern and encoded onto the hydrogel.

This isn’t the first time scientists have taken inspiration from octopus anatomy. In 2021, engineers at Rutgers University created a 3D printed synthetic muscle that subtly changed its shape when exposed to light. More recently, researchers at Stanford developed a flexible, synthetic material that would swell and change size when targeted with a beam of electrons. Elsewhere, roboticists have even developed octopus-like, slightly terrifying “Tentacle Bot” outfitted with mechanical armies and suckers that helps it move around and grab objects.