After completing the first ever transatlantic airship flight in October 1928, the majestic Graf Zeppelin, a 776-foot gleaming dirigible, was greeted with fanfare wherever it flew; its lighter-than-air design captivated onlookers as it effortlessly circled city skylines. In its later years, the vessel became a tool of Nazi propaganda, with swastikas emblazoned on its 65-foot fins, transforming it into a symbol of war, terror, and aggression, like many of its World War I predecessors.

But in 1929, the Graf Zeppelin—also known by its serial number LZ-127, which stood for Luftschiff (“airship”) and the name of its creator, Ferdinand von Zeppelin—was still in the early days of its pre-Nazi chapter. On August 29, 1929, it became the first human-made craft to circumnavigate the globe by air, using Lakehurst, NJ as the port where its American journey began and ended. (The trip was strategically planned with a transatlantic overlap that allowed Germany to claim the flight had begun and ended in Freidrichshafen—the airship’s home port.)

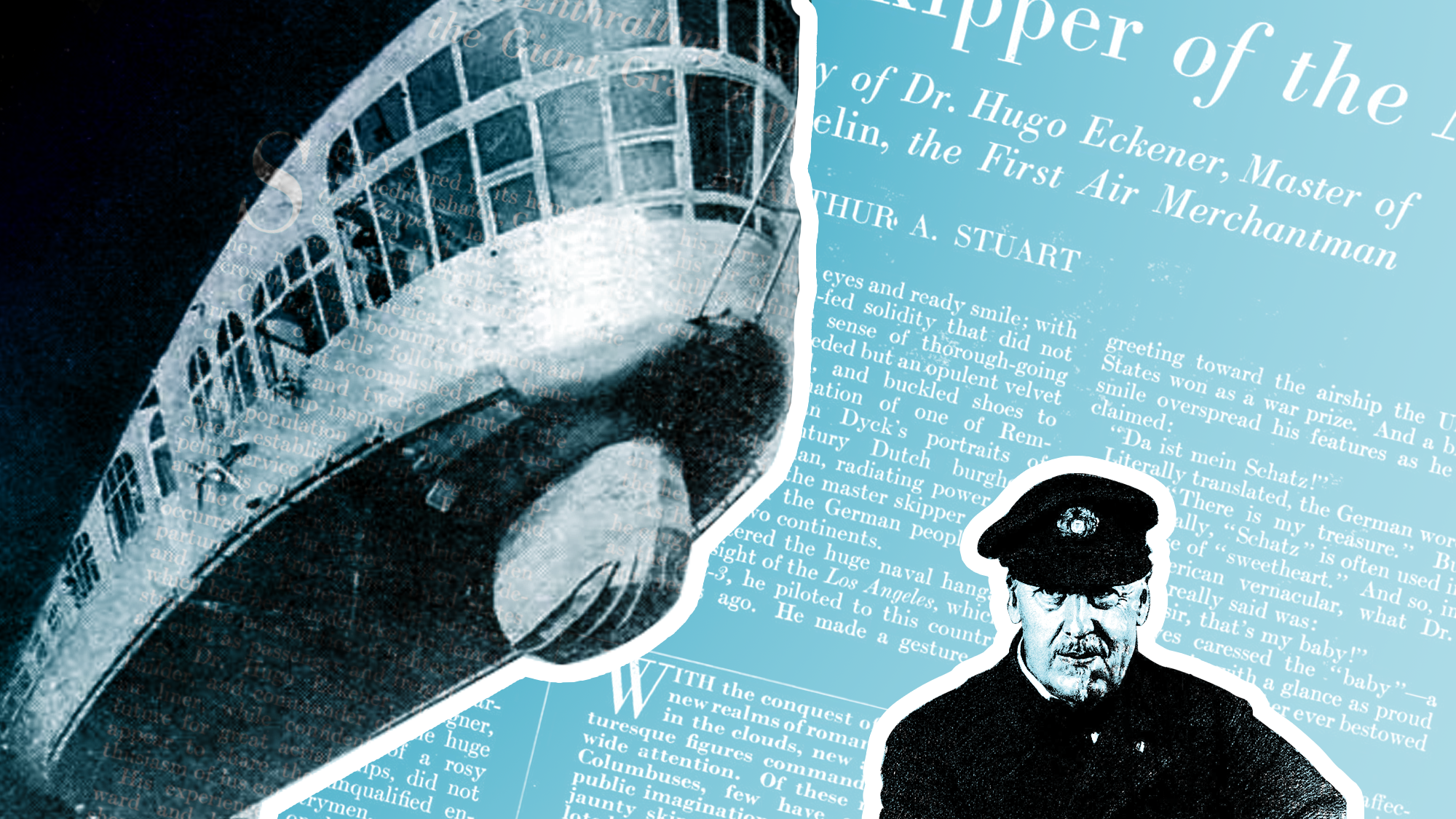

Earlier that year, in January 1929, Popular Science profiled the Graf Zeppelin’s pilot, Hugo Eckener. (The article is reproduced following this introduction.) More than just the airship’s captain, Eckener was also head of the Zeppelin Works at Freidrichshafen, a scientist and aeronautical engineer, with doctorate degrees in economics and psychology. He designed and built the Graf Zeppelin, which Popular Science writer Arthur Stuart described as embodying all of Eckener’s theories of dirigible transportation. Stuart wrote, “It is the fruit of his quarter-century of experience as a builder of great aircraft. Into it, he has poured all his skill as an engineer and his genius as a designer of lighter-than-air vessels.”

Eckener’s career spanned most of the golden age of airships, a period that lasted roughly two decades and ended shortly after the Hindenburg exploded in a ball of fire while docking at Lakehurst, NJ in 1937—a tragedy that spotlighted the perils of airship travel. During their heyday, however, Eckener had set his sights on creating a reliable transoceanic commercial airship passenger service. The Graf Zeppelin became the first to achieve Eckener’s vision, ferrying thousands of passengers in luxurious accommodations across the Atlantic, mostly between Germany, Argentina, and Brazil. The trips took three to four days, much faster than traveling by train and ocean liner, which could take weeks. The Hindenburg later became the Graf Zeppelin’s North American counterpart, traveling between Europe and the United States in two to three days.

It was publishing tycoon William Randolph Hearst who funded the Graf Zeppelin’s journey around the world. The flight departed Lakehurst, NJ on August 7, 1929, making stops in Freidrichshafen, Tokyo, and Los Angeles before returning to Lakehurst on August 29th. “With the conquest of the air new realms of romance loom in the clouds,” Stuart wrote in 1929.

If traveling by airship seems like a dreamy way to explore the world, efforts are underway by airship enthusiasts to resurrect such possibilities. For a cool $200,000 (for a 2-passenger cabin), OceanSky Cruises plans to offer roundtrip voyages to the North Pole from Norway’s Svalbard islands and a separate air-expedition called Capricorn that will glide above the African continent. But sky yachting is just one way in which airships may return. Google founder, Sergey Brin, has invested in prototypes that could be used to ferry humanitarian aid into difficult-to-reach places. And UK-based Hybrid Air Vehicles, which manufactures the Airlander, touts the climate-friendly features of its airships, including 90 percent fewer CO2 emissions than conventional aircraft. Even though it may take a few days longer than a plane (not to mention the six-figure ticket), when traveling by airship, you’ll at least definitely have time to catch some Zs and adjust to your new timezone while in flight.

The original 1929 profile is republished below.

SAFELY stored in its home hangar at Friedrichshafen, Germany, the Graf Zeppelin, largest aircraft in existence and the world’s first commercial dirigible, rested after her record-breaking eastward Atlantic crossing from America.

Greeted with booming of cannon and ringing of bells following a trans-oceanic flight accomplished in seventy-one hours and twelve minutes, the great airship inspired an elated German population with hopes of the speedy establishment of a regular Zeppelin service between the Fatherland and this country.

The Graf’s arrival in Friedrichshafen occurred just three weeks after her de- parture on a trip to the United States and back. Reviewing the journey, which had been undertaken to demonstrate the possibilities of lighter-than-air craft as passenger and freight carriers, Dr. Hugo Eckener, designer, builder, and commander of the huge air liner, while confident of a rosy future for great aerial ships, did not appear to share the unqualified enthusiasm of his countrymen.

His experiences on both the out- ward and homebound courses had shown him, Dr. Eckener announced upon landing, that quicker and strong- er dirigibles will have to be built before regular passenger service can be established with fair expectation of continued safety and success.

This opinion of his tallied with views he expressed to me shortly after his arrival on this side of the Atlantic. Desirous of seeing the latest wonder of the air, and more especially of meeting the man who constructed her and piloted her safely across the water, I went to Lakehurst, N. J., where the huge Naval hangar, harbor of the proud Los Angeles, was to house the Graf during her stay in America.

IT WAS 5:88 o’clock of a bleak and chilly autumn evening, when the Zeppelin touched American soil after a storm-ridden voyage from Germany, during which she covered 6,300 miles in one hundred eleven and one-half hours of record-breaking nonstop long distance flight. The builder and skip- per of this new leviathan of the air and of her sister, the Los Angeles, before her, stepped down on terra firma and quickly crossed the field to the hangar.

Of generous proportions, gray-thatched, ruddy-cheeked, Dr. Eckener resembled a sailor more than a flyer, an admiral rather than an aviator. With his jaunty, clipped moustache and diminutive chin-whisker, his merry blue eyes and ready smile; with his air of well-fed solidity that did not dull a definite sense of thorough-going efficiency, he needed but an opulent velvet costume, sword, and buckled shoes to an incarnation of one of Rem-” brandt’s or Van Dyck’s portraits of seventeenth century Dutch burghers.

This portly man, radiating power and good nature, is the master skipper of the air, the idol of the German people, and the hero of two continents.

As he entered the huge naval hangar, he caught sight of the Los Angeles, which, as the ZR-3, he piloted to this country four years ago. He made a gesture of greeting toward the airship the United States won as a war prize. And a broad smile overspread his features as he exclaimed:

“Da ist mein Schatz!”

Literally translated, the German words meant: There is my treasure.” But colloquially, “Schatz” is often used in the sense of “sweetheart.” And so, in the American vernacular, what Dr. Eckener really said was:

“Yes, sir, that’s my baby!”

His eyes caressed the “baby”—a 656-foot one! with a glance as proud and tender as any father ever bestowed on his child.

THE gesture, the words, the affectionate look-they all were typical of the big, jovial Commodore, who, despite his many university degrees, his commanding position as head of the Zeppelin Works at Friedrichshafen, his achievements as a scientist and engineer, and his unique accomplishments as builder and master of the largest aircraft ever conceived, has remained so thoroughly human that thousands of little Gretchens and Fritzes in the German schools volunteered their pfennigs when it became known that “der grosze Luft Kapitaen” (the great air captain) had appealed to his people and government for financial aid in building the Graf Zeppelin.

A kindly soul offered him a huge cigar—a veritable Zeppelin among weeds. Lighting it with elaborate care and drawing the first puff, he sighed with intense contentment and said:

“Ah! The first in four and a half days!”

Seldom have I seen so much relish and enjoyment expressed in a human countenance.

Then he was ready to tell the story of the historic flight, for though he had slept only eight hours out of the one hundred eleven and one-half the trip required, he appeared fresh and unwearied.

HE TOLD how he undertook the voyage regardless of bad-weather warnings to prove the air-worthiness of his great ship as a passenger liner and mail and freight carrier. And proudly he emphasized that “the little accident,” as he called the ripping of the port horizontal stabilizer in a storm 2,000 miles out over the Atlantic ocean, had served to help him prove his point!

For the most part, he spoke in correct English with a strong Teutonic accent. But every so often our language proved a bit too much for him and he slipped back into his native tongue. “Well, you know,” he began, “that the weather over the Atlantic in the last few weeks had been very bad. So I had to make a special kind of trip. I could not go right out straight across the Atlantic, and yet I felt I must go, once our ship was completed.”

He took couple of puffs at his cigar and went on:

“I was bold. I was bold enough to say that the weather would not keep me from starting out as soon as the ship was finished. That put me in the position of either being a liar or making the trans-Atlantic voyage. So go we did. But because of the weather over the ocean, we had to go by way of Spain and Gibraltar, and that added 1,200 statute miles to the journey! From Gibraltar by the way we came, near the Azores, it was a little more than 5,000 miles to our destination in America.”

I WANTED to know the details of the accident that tore the fabric from the lower side of the port fin, in the repair of which four members of the crew, led by Dr. Eckener’s own twenty-four-year-old son, Knut, covered themselves with glory. It was evident that the Commodore did not deem this occurrence worthy of much mention.

The storm Dr. Eckener called “a squall,” and to the mishap which brought a message to the United States Navy to stand by with rescue ships he referred as “a little accident.”

“Well,” he said, “we were struck by wind as we went along smoothly at seventy-five miles an hour, with every motor turning perfectly.

“There was a sudden increase in the wind and rain came with it-a real squall. The Graf Zeppelin shot upward to an angle of forty degrees or so. The young helmsman on duty tried to bring her back to a horizontal plane, and in doing this he put a sudden strain on the stabilizer and that burst the fabric.

“The stuff caught in the wind. It was ripped away for something like a hundred square yards. Of course, it had to be repaired at once or more of the covering would go.

“It was a little accident,” Dr. Eckener continued. “It never happened before in the history of Zeppelins and it can never happen again! Naturally, we were handicapped by it. It happened at eight o’clock in the morning and the trouble was fixed at one o’clock in the afternoon. In those five hours, we stood al- most entirely still. And even after the repairs had been made we could only proceed at half speed.”

HERE I interrupted. “Tell me about the ‘repair job! Wasn’t your son one of the riggers who went up to fix it?” I asked.

The Commodore’s face glowed with unmistakable parental pride and pleasure. “All right, then,” he smiled; “all right.”

But this was a rather personal matter, and the English words refused to come easily. So he told me in the most polished German how Knut and the three others had repaired the damage.

As he talked, I saw an intensely dramatic picture of four young fellows running up the cat-walk into the tail of the ship, scampering up the girders of the frame that meets the fin at that point, and then, one by one, armed with shears and knives, mere pygmies in com- parison with the monster whose wound they set out to bind up, climbing out over the ocean on the spars that make up the frame of the fin, clear out thirty feet along the duralumin beam, with nothing between them and the roaring, storm-swept Atlantic but 1,500 feet of air!

Clinging desperately to their perilous perch, beaten by storm and rain, tossed up or down fifty or a hundred feet and climbing back and forth as the tail of the Zeppelin swung on the fickle wings of the wind, they succeeded in cutting away the hanging shreds. They never stopped for a moment until the job was finished-fully five hours with no let-up in the storm.

But Captain Flemming, who was at the controls in that soul-trying hour, told me a slightly different tale.

Knut was the first to volunteer. When he and the three others had crawled way back to the damaged fin and the Graf was practically standing still, Flemming turned to the Commodore and said:

“We must start two engines.”

Dr. Eckener knew that if he ordered the motors started the wind might tear his son, and perhaps the others, too, off that precarious place and hurl them to the waves below. But the stern of the ship was beginning to sag under the deluge of rain, and so he also knew that he must move to try to maneuver out of the “squall.”

“MUST have two motors,” Flemming repeated.

The Commodore’s face suddenly grew very old. He looked out of the window in his favorite corner of the bridge. He swallowed hard. There was no telephone communication be- tween the bridge and the fin, where Knut hovered between clouds and water. Then he said huskily:

“Start the motors!”

What Dr. Eckener went through from that minute until his son climbed down to the con- trol room five hours later to report that the repairs had been made, only he and Heaven know.

“Were the passengers frightened?” I asked Dr. Eckener.

“To tell you the truth,” was his reply, this time again in English, “I was so busy on the bridge that I hadn’t time to go into the passenger-cabin to find out how the passengers felt.

“I did so as soon as we were under way once more. I found them calm, and reassured them as to the rest of our trip. Then we got out a bottle of nice wine and had a little toast and we all felt happy again.”

But a somewhat different version of what happened right after the fin had been fixed was given me later by one of the passengers.

“You know,” said this man, “Dr. Eckener bad a pet canary aboard, whose double function it was to sing to him and to act as a gas-detector. The Commodore seemed unusually attached to this bird. Now, the moment Knut had come down and reported that the stabilizer was all right again, Dr. Eckener left the control cabin and went aft to look after his canary. He found the bird in high spirits, singing away at the top of his voice, and he calmly fed him. As a matter of fact, we passengers had been greatly upset, but when we heard about this, our fears were put to rest.”

As Dr. Eckener was finishing his story of the voyage in the flight office, somebody handed him a slip of paper. It was a radiogram, but as it was penciled hastily in English, he handed it to one of the bystanders for translation. It proved to be a message from Dr. Eckener’s wife.

“She sends love and congratulations on your birthday,” said the interpreter.

It then developed that the radiogram had been delayed for some reason and that the Saturday when the “little accident” in mid- ocean occurred had been Dr. Eckener’s sixty-fifth birthday!

Dr. Eckener told me of his views regarding the future of trans-Atlantic dirigible transportation and of the lessons his recent experience taught him.

He predicted the establishment of a regular airship service between the United States and Germany in three or four years, with a dirigible leaving from each side of the Atlantic every five days and making the crossing in between forty-five and fifty hours!

But to make such a service possible, he said, a capital of $14,000,000 will have to be raised for the building of four Zeppelins—two in this country and two in Germany—and the construction of two hangars, each large enough to harbor two of the giant ships at one time. Of the required sum of $14,000,000, the building of the dirigibles would take $8,000,000, and the balance of $6,000,000 would be necessary to erect the hangars.

THE Commodore then stressed the fact—which he was to emphasize again in Germany later that his voyage in the Graf Zeppelin had shown him that speedier ships will be required for regular transoceanic traffic.

“The airship of the future,” he told me, “will only be slightly larger than the Graf Zeppelin, but it will be more swift. It will develop an average speed of eighty or eighty-five miles an hour, preferably eighty-five. It will carry but few passengers and will be chiefly used for carrying mail and merchandise.”

Dr. Eckener also admitted that the trip had taught him that stronger fabric must be used for the stabilizing fins and the tail.

The Commodore’s forecast regarding the creation of a regular Zeppelin service, though perhaps not quite so sanguine, was in line with enthusiastic views he expressed a little more than a year ago, when he made his last previous visit to the United States. At that time he came and went by steamer and remained in this country only a short while to complete some business arrangements.

Then he visualized a dirigible trip around the world in twelve days—a dream that may well have caused the late Monsieur Jules Verne to turn in his grave!

Although his short sojourn in the United States in 1927 was little known publicly, Dr. Eckener is by no means a stranger to America and Americans.

When, in October 1924, the time came for the delivery flight of the ZR-3, now the Los Angeles, to the United States, Commodore Eckener himself took the controls and acted as commander of the ship on the voyage from the hangar at Friedrichshafen to the Naval hangar at Lakehurst. This was the longest nonstop trip ever made by aircraft up to that time.

UPON his arrival here, the Commodore won instant popularity, and on his return to his native land, he found himself received with all the enthusiastic honor and acclaim usually reserved for a triumphant war lord! He was repeatedly mentioned for the German ambas- sadorship to the United States and even for the Presidency of the German Republic. But he smilingly though steadfastly declined these high distinctions.

“My life,” he said, “is bound up in the building of airships. I am not a diplomat nor a politician.”

And he was right. At least, the last twenty-eight years of the Commodore’s remarkable career have been devoted to the development of the dirigible as a means of safe and swift transportation.

It was in 1900 that the meeting took place that proved the turning point in Dr. Eckener’s life. On the shores of Lake Constance, near the Swiss-German border, where he had decided to settle down as a writer and publicist on subjects related to economics, his specialty up to that time, the Commodore became acquainted with Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, inventor of the dirigible that bears his name. There began a friendship that endured until the Count died seventeen years later. On almost daily walks along the beautiful blue lake, the Count, who already had begun to build rigid airships, expounded his theories and hopes.

For a long time, Dr. Eckener, an eminently practical soul, remained skeptical. But at last he became convinced of the soundness and practicability of the Graf’s ideas, and he joined the Zeppelin organization.

Now Dr. Eckener, though an economist, was a navigator by nature. His talents along this line and his extraordinary gifts as a meteorol- ogist became of great value to Count Zeppelin, and the subsequent development of airship operation was largely due to his efforts.

HUGO ECKENER was born in Flensburg, in Schleswig-Holstein. As a boy, his passion was the sea, and much of his leisure was devoted to navigating a small sailboat over the choppy waters of the Baltic Sea. Even as a lad of high school age, he enjoyed some fame for his courage and resourcefulness as a sailor and his skill as a meteorologist. For this youth, in some unknown fashion, had developed an unusual and almost uncanny ability to forecast the weather.

But the sea was not to be his career. The Eckener parents had determined that Hugo should become a man of science—a Herr Professor!—and to college he was sent. Here he specialized in economics, in which subject he took his doctorate with honors, a circumstance that explains his present thorough grasp of business and financial problems.

He also studied psychology at the University of Leipzig, which conferred a doctor’s degree upon him in that subject.

All of the airship pilots in Germany were trained by Dr. Eckener, and in 1912 his work was extended to cover the commercial oper- ations of the Zeppelin organizations under a subsidiary company called “Delag,” of which he was made director.

During the two years just previous to the World War, Delag ships carried some 35,000 passengers and many tons of freight and ex- press without a single accident.

COUNT ZEPPELIN died in 1917 and was succeeded by his nephew, Baron von Gemmingen, who passed away in the spring of 1924, when Dr. Eckener was made the third pre- siding head of the Zeppelin organization.

During the war, the Friedrichshafen plant had been built up to a capacity of one dirigible every two weeks! The technical problems surmounted at that time by Dr. Eckener, who throughout the period was Count Zeppelin’s right-hand man, were the more complex because of the shortage of materials in Germany. Immediately after the war, it was thought at first that the Zeppelin plant would be destroyed. It was shut down, and Commodore Eckener was heartbroken.

It was not until after the famous flight of the ZR-3 that the fate of the plant was finally decided. France insisted that it be destroyed. The German patents passed to the Goodyear-Zeppelin Company, of Akron, Ohio, at that time, and the Zeppelin works lost many of its secrets.

But the last few years of phenomenal aircraft development gave Dr. Eckener new hope of a real future for the plant, and on the wave of world-wide enthusiasm for aviation, he began the construction of his masterpiece the Graf Zeppelin.

The enormous sky-ship embodies all of Dr. Eckener’s theories of dirigible transportation. It is the fruit of his quarter of a century of experience as a builder of great aircraft. Into it he has put all his skill as an engineer, all his genius as a designer of lighter-than-air vessels.