Watch this French laser zap drones out of the sky

The system is one way for militaries and others to deal with rogue drones. Pew, pew!

A small French company called CILAS has been testing its laser system, downing a number of different drones flying at more than 30 mph and up to 3,300 feet away. It marks the first time in Europe that drones were downed by laser.

Lasers like this have an advantage when it comes to swatting pesky drones out of the sky: they will fry up and burn whatever they have hit. But the beam will go no further, causing no collateral damage. They are very precise, have a long range, and are extremely fast.

Tanguy Mulliez, manager of the innovation and products department at CILAS, which specializes in lasers, tells Popular Science in a telephone interview: “It’s like the beam of a flashlight. It stops at whatever object it hits first.” He adds that “the great advantage of a laser system is that it can also be used for other missions,” such as neutralizing explosives, destroying electronics, taking out light sensors, and jamming cameras by blinding them.

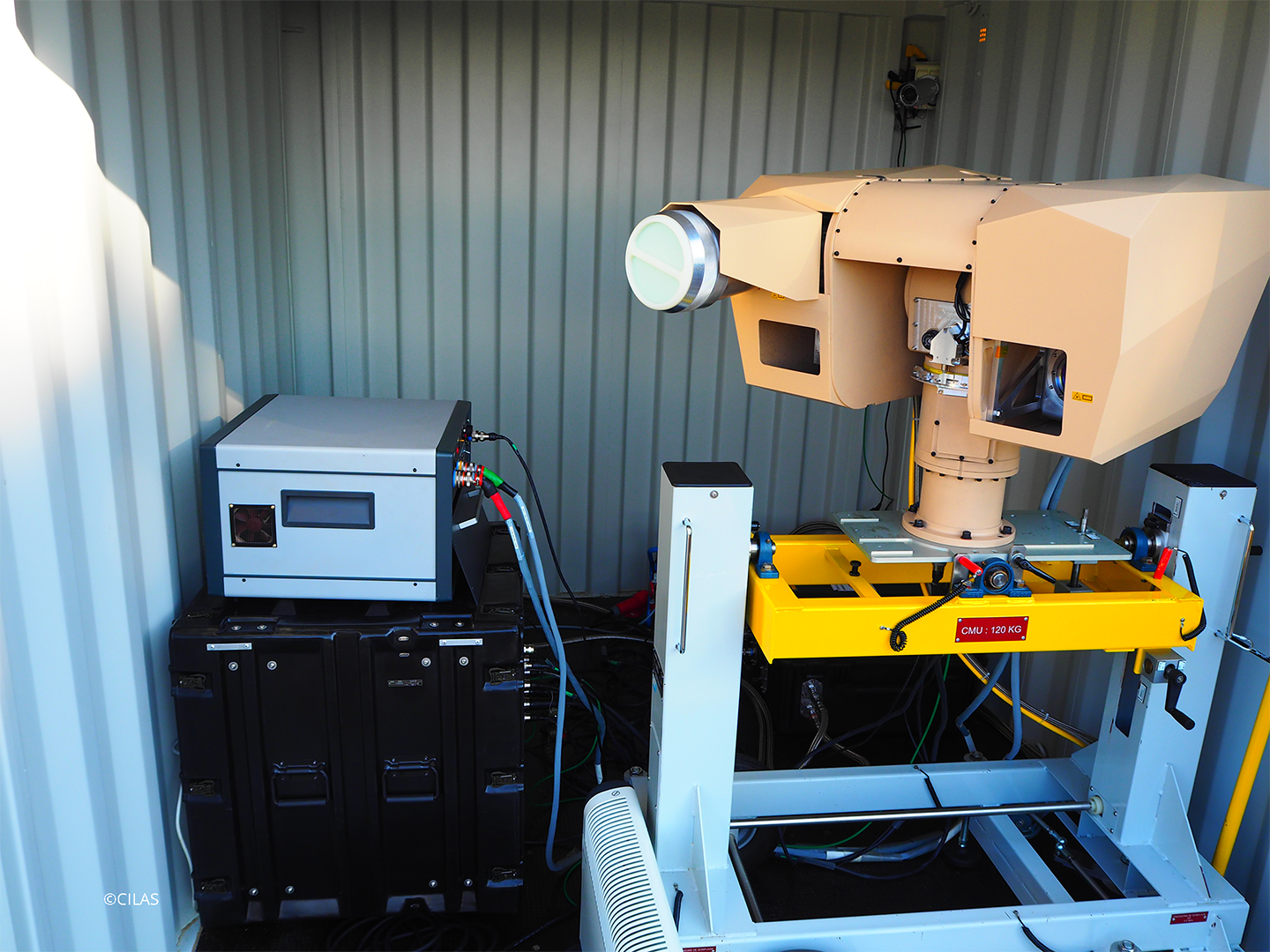

The system is called the HELMA-P, which stands for High-energy Laser for Multiple Application – Power. “These demonstrations made a real impact on the military and they’ve come back with a lot of questions that we’re working on, both for France and other clients,” Mulliez adds.

“A laser weapon is not very concrete in many people’s minds as it can be neither seen nor heard so we decided in 2017 to develop a demonstrator,” Mulliez explains. He remarked that “over the past three years a lot of laser products have emerged so we have many competitors.” Those are large companies in the United States, Russia, China, Israel, and Germany that are working on “very big” laser projects.

This does not phaze CILAS. “We might be small, but we are laser specialists and we did not aim for the top-end of the market,” Antoine Vautrin, head of export sales at CILAS, adds via phone.

Vautrin explains that “development of the prototype is very advanced so it’s practically ready for the market.” He says that the company would make further demonstrations for potential military and civilian clients who can have HELMA-P customized. The civilian clients are other companies, weapons systems suppliers, who will include HELMA-P as part of their system.

[Related: The US military is testing a microwave anti-drone weapon called THOR]

During the demonstration, the laser was guided manually and the target drone was tracked by a French military radar. But the laser can be linked to any command and control system that has at least two cameras (one looking at the overall scene and one tracking only the drone). The data from the two cameras allows the exact position and distance of the drone to be established.

Lasers come with different amounts of power. The one you might use as a pointer during a slide presentation is below 0.005 watts, and the most powerful hand-held lasers available to the general public are no more than 3 watts. The United States Air Force recently acquired a High-Energy Laser (HEL) Weapon System made by Raytheon. The laser beam on that weapon is 10 kW, or 10,000 watts.

The French HELMA-P’s exact power is classified, “but it’s single digit [in kW],” Mulliez said.

A more powerful version of the system is already in the works. The small French company is the leader of a $6.6 million, 36-month European program (which ends on Sept. 1, 2022) called Talos (Tactical Advanced Laser Optical System) that comprises 16 companies from nine countries. They are working on the HELMA-XP, which would have “two or three digit kW power,” Vautrin says. Some of the technologies to be demonstrated, apart from the laser itself, include atmospheric turbulence compensation, laser pointing systems, and precision target tracking.

[Related: The Coyote swarming drone can deploy for aerial warfare—or hurricanes]

Systems like this are in development because drones are common, and they can be a bit of a security headache. The smaller ones, cheap and widely available to the general public, are typically the ones causing the trouble.

Some amateur pilots fly them into reserved airspace around airports and sensitive sites such as nuclear power plants or military compounds, unintentionally. Others fly them there on purpose. For example, London’s Gatwick airport shut for 33 hours in December of 2018 because drones were reported to be flying around the runways. Additionally, sometimes they could be flown to draw attention to an environmental issue, to take illegal photographs, or just for fun. And then there are the truly ill-intentioned: the criminals and terrorists who might arm their drones to kill, maim or cause chaos.

So a whole new industry has emerged over the past few years to counter them. There are systems to detect them, systems to hone in on them, and systems to capture them or put them out of action. Among the latter are drones designed to crash into other drones; drones armed with nets; and systems to jam the signal being sent by the operator to the drone. And of course, there are lasers like the HELMA-P.

This article has been updated to correct an error with the spelling of Antoine Vautrin’s name.