This was a bad week for spies, and a great week to find out how we were spied on. Following revelations Wednesday that Verizon handed over millions of call records to the National Security Administration, news broke Thursday that the FBI and NSA had access (probably not direct) to servers for nine U.S. internet companies. The name of this program is PRISM, as a reference to splitting light on fiber-optic cables.

Authorization for this program dates back to an anti-terror surveillance bill passed by Congress in 2007. While aimed at finding communication between foreign terrorists, the language was broad and never restricted government surveillance of communications between people within the United States. Instead, the NSA uses a rough metric to make sure they are only listening to communications with 51 percent confidence in their “foreignness,” which sounds ridiculous because it is. The legislation was supposed to expire in six months, but many of its provisions were reauthorized by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 2008.

The PRISM program grew from this authority. President as a rule regard themselves: as the primary judge of what information to share and what to withhold on grounds of executive privilege or national security

The White House then chooses how much of this information to filter down to Congress. Under the Constitution, the President has primary authority and responsibility for foreign affairs and national security. This primacy, combined with the vast array of intelligence collection agencies under the executive branch, create an institutional bias towards intelligence collection as a preventative measure against terror attacks. This is heightened by repeated coverage of the intelligence collection and communication gaps that failed to prevent the September 11th, 2001 attacks, creating a strong incentive for a sweeping data collection apparatus.

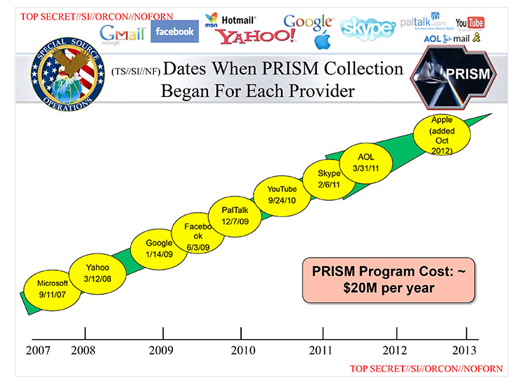

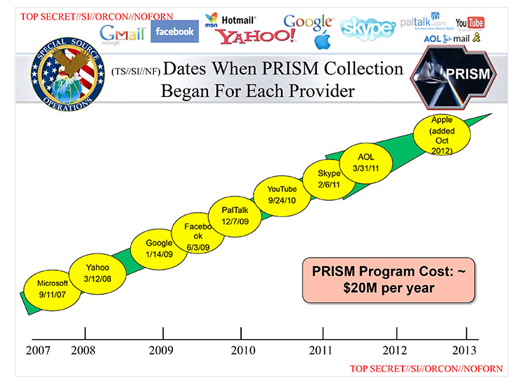

PRISM itself doesn’t generate new information. Instead, it perches atop the architecture of the internet like a gargoyle, and gathers everything that passes through. PRISM currently accesses data from nine companies: Micrsoft, Google, Yahoo!, Facebook, PalTalk, YouTube, Skype, AOL, and Apple. Microsoft joined first in 2007, with Apple becoming part of the program last, in 2012. While the law that authorized this program was set to expire in 2012, Congress passed a re-authorization extending it to 2017.

Information is pulled from the servers of these companies, again with the goal of finding communications between foreign terrorists and people within the United States. Rather than looking for direct linkages, however, it just hoovers up an obscene amount of information and assumes the connections will reveal themselves later in analysis.

On its own, the program is unlikely to catch a terrorist. Corey Chivers ran a Bayesian probability analysis of the program, and by his math: for every positive (the NSA calls these ‘reports’) there is only a 1 in 10,102 chance (using our rough assumptions) that they’ve found a real bad guy. That’s an insane false positive ratio for a program, which makes it very unlikely that the program is actually being used to find specific terrorists. Instead, my hunch is that this builds cases backwards, creating an available log of information for individuals that can be brought up as supporting evidence when hard evidence emerges.

When asked about PRISM at a Friday afternoon press conference, President Obama responded: “I think it’s important to recognize you can’t have 100 percent security and also 100 percent privacy, and also zero inconvenience. We’re going to have to make some choices as a society.”

Such trade-offs are inevitable in society. In order to do so, however, we need a modern, updated, legal understanding of privacy. The laws that govern email, for example, treat it only as private when unopened in an inbox, because law is based on an understanding of mail that dates back to physical letters. Metadata on phonecalls, which made news earlier this week when the government obtained it in the millions from Verizon, is based on law that largely predates mobile phones and GPS location tagging. The privacy of individual information, as held by companies online and in electronic storage, is governed by company policy and unread Terms of Use agreements, but the way the law exists and is defined doesn’t reflect actual assumptions of privacy, and people use this technology under the false premise that it is far more private than it actually is.

PRISM is a technically legal way for the government to bypass privacy in the interest of national security, but no part of how it operates fits in with the privacy people (albeit falsely) assume they have online. Congressional action, as well as more modern legal rulings on privacy, are what it would take to bring the law around to common usage.

Until then, expect programs like PRISM to remain a part of online life in America.