Extreme Engineering: The Deepest Oil Well

Even the worst economy in decades can’t suppress the human urge to build. Today’s most ambitious projects are bigger and wilder than ever!

Name: Perdido Spar

Where: Gulf of Mexico

Cost: Undisclosed

Estimated Completion: First oil, 2010; all wells online, 2016

The Challenge: Moor a skyscraper-size floating rig to the seafloor, then drill the world’s deepest subsea well

Two hundred miles off the coast of Galveston, Texas, below 10,000 feet of water and another 9,000 feet of mud, salt and rock, lies Shell Oil’s most ambitious new target, a swath of seabed the size of Houston that holds enough oil and natural gas to produce up to 130,000 barrels a day.

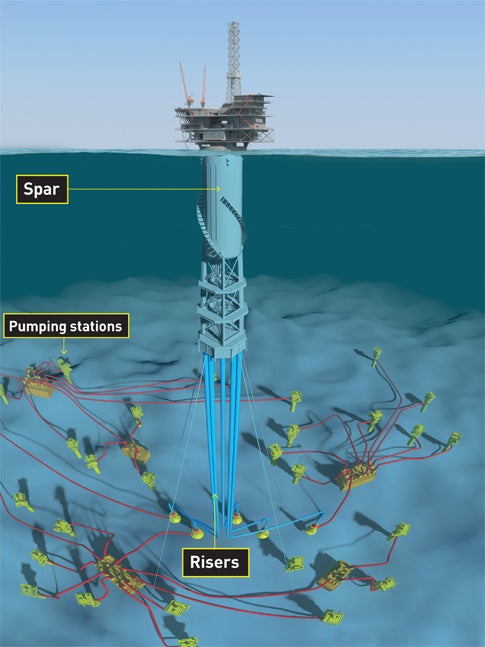

Last summer, the company constructed a floating 50,000-ton rig and anchored it to the seafloor over the area known as the Perdido foldbelt. The ancient crude there is locked inside rock riddled with fractures and fault lines. To access it, engineers plan to drill 22 wells in the seafloor below the rig, and another 13 wells nine miles away. Traditionally, each well is connected back to the rig by its own pipe that hangs from the spar. But the weight of just one two-mile-long pipe is 500 tons — to support 22 of them would require a spar four times as big as Perdido.

Instead, the rig will have only five pipes, called risers, hanging down to the seafloor. From there, they will branch out into clusters of connected wells. This setup solves another problem: There’s only enough natural pressure inside the reservoir rock to boost the oil and gas to the seafloor, not all the way to the rig. So truck-size machines at the base of each riser will first separate the oil from the gas and then push both fuels up the pipes with 1,500-horsepower pumps.

Tapping the Perdido spar won’t produce enough oil to change the price at the pump. (America consumes about 20.7 million barrels of oil a day.) But perfecting the technology to unlock the wells opens up hundreds of other oil-rich targets in the Gulf’s deep water.