Only about 30 percent of embryos implanted for in-vitro fertilization result in the birth of a healthy baby. One of the reasons IVF might fail is that the embryo (or embryos) that doctors implant into the prospective mother might not stand the best chance for healthy development.

Now scientists from Stanford University believe they have found a new way to assess an embryo’s viability before it’s implanted: by checking its squishiness, just as you do in the grocery store to see if a fruit is ripe. The finding could lead to more successful pregnancies that are safer for both mother and child. The researchers published their findings yesterday in Nature Communications.

The researchers became interested in this idea when the director of Stanford’s IVF laboratory mentioned to some colleagues that some embryos are squishier than others. Typically, when clinicians are preparing embryos to be implanted in the mother, they combine several eggs with the father’s sperm, then wait a few days to see which embryos are developing the quickest. The clinicians use that quick cell division as an indication of the embryo’s health, and they usually implant a few of those in the mother because, more often than not, some (or all) of the embryos end up not being viable. Or, if they’re both viable, IVF can often result in twin births, which can put the lives of the fetuses and of the mother in danger.

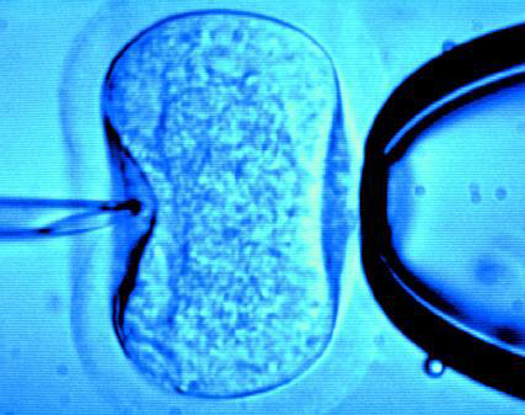

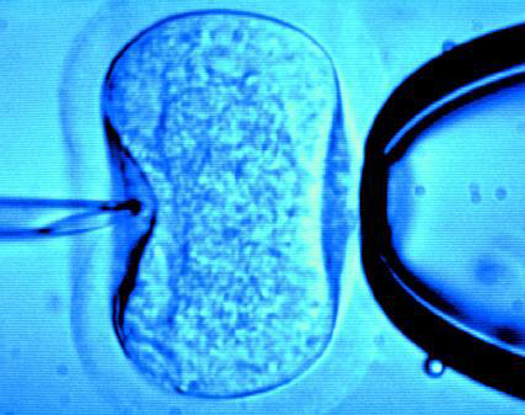

The team first tested the squishiness of mouse embryos by using a pipette to poke them a little bit. They figured out a range of squishiness that likely showed embryos which were the most viable–the ones that were too squishy or too hard were less good than the ones that were in the middle, just right. Then the researchers implanted the embryos into mouse moms to make sure. Their computer model used squishiness to predict which embryos would have the right amount of pre-implantation cell division with 90 percent accuracy.

Then the researchers tested the same thing with human embryos—assessing their squishiness, coming up with a range, and predicting which ones would have promising cell division with 90 percent accuracy. They haven’t yet checked their outcomes by implanting these embryos in human mothers, but they plan to do so in the near future.

There are still a number of questions, like why exactly squishiness is a good predictor of viable embryos, though the scientists suspect it have something to do with DNA repair and the embryo’s ability to position itself properly as cells replicate.

If an embryo’s mechanical properties can predict its viability, that could make each embryo implanted via IVF much more likely to succeed, which would also help clinicians limit the number of twins born as a result of IVF. It could have implications beyond traditional IVF, too—as mitochondrial DNA transplants (“three-parent babies”) get closer to clinical practice and cutting-edge fertility treatments could extend the time in which women can have children, more patients would benefit from reliably using only the most viable embryos.