Number 10: Whale-Feces Researcher

They scoop up whale dung, then dig through it for clues

“Brown stain ahoy!” is not the cry most mariners long to hear, but for Rosalind Rolland, a senior researcher at the New England Aquarium in Boston, it´s a siren song. Rolland, along with a few lucky research assistants, combs Nova Scotia´s Bay of Fundy looking for endangered North Atlantic right whales. Actually, she´s not really looking for the whales-just their poo. “It surprised even me how much you can learn about a whale through its feces,” says Rolland, who recently published the most complete study of right whales ever conducted. “You can test for pregnancy, measure hormones and biotoxins, examine its genetics. You can even tell individuals apart.”

Rolland pioneered whale-feces research in 1999. By 2003, she was frustrated by the small number of samples her poo patrol was collecting by blindly chasing whales on the open ocean. So she began taking along sniffer dogs that can detect whale droppings from as far as a mile away. When they bark, she points her research vessel in the direction of the brown gold, and as the boat approaches the feces-the excrement usually stays afloat for an hour after the deed is done and can be bright orange and oily depending on the type of plankton the whale feeds on-Rolland and her crew begin scooping up as much matter as they can using custom-designed nets. Samples are then placed in plastic jars and packed in ice (the largest chunks are just over a pound) to be shared with other researchers across North America. “We´ve literally been in fields of right-whale poop,” she marvels.

In the past few years, other whale researchers have adopted Rolland´s methods. Nick Gales of the Australia Antarctic Division now plies the Southern Ocean looking for endangered blue-whale dung, a pursuit that in 2003 led him to a scientific first. While tailing a minke whale, Gale´s team photographed what is believed to be the first bout of whale flatulence caught on film-a large, disconcertingly pretty bubble trailing behind the whale like an enormous jellyfish. “We stayed away from the bow after taking the picture,” Gales recalls. “It does stink.”

Number 9: Forensic Entomologist

Solving murders by studying maggots

“One day a local detective called me who knew I´d majored in entomology in college and said, “Hey, Neal, we got a body at the morgue with insects on it. You wanna give it a shot?´ The corpse turned out to be a guy I used to have breakfast with, and there were maggots in his teeth. Then I found some in his eyes, and I thought, “This is what I want to do. This is just way too cool.´”

Neal Haskell´s eagerness could easily be interpreted as insensitivity. But it takes a unique sensibility to rise to the top of his particular field. Now, 700 maggot-infested corpses later, the former Indiana farmer is one of the nation´s leading forensic entomologists, teaching at St. Joseph´s College, testifying in roughly 100 cases, and co-authoring the first entomology book for law enforcement. His job, like that of the country´s 20 or so other insect investigators, is to estimate the “postmortem interval” (the time between death and the body´s discovery) by charting the life stages of the blowfly, the world´s predominant cadaver connoisseur.

Neal Haskell´s eagerness could easily be interpreted as insensitivity. But it takes a unique sensibility to rise to the top of his particular field. Now, 700 maggot-infested corpses later, the former Indiana farmer is one of the nation´s leading forensic entomologists, teaching at St. Joseph´s College, testifying in roughly 100 cases, and co-authoring the first entomology book for law enforcement. His job, like that of the country´s 20 or so other insect investigators, is to estimate the “postmortem interval” (the time between death and the body´s discovery) by charting the life stages of the blowfly, the world´s predominant cadaver connoisseur.

Picking through rotting corpses for eggs, maggots, pupa and adult blowflies-as well as the larvae of odd species like cheese skippers, a type of fly fond of cheddar, ham and human fat-FEs can help estimate time of death (essential in a murder case) by determining when decomposed bodies first became critter food.

Occasionally forensic entomologists get a case that requires more participatory research. To help solve a crime in Cleveland, for example, Haskell mimicked the case details by wrapping 17 dead pigs (“they approximate human corpses surprisingly well”) in plastic to determine the order in which flies are likely to colonize bagged corpses. “I´ve done an awful lot of neat things in my life,” Haskell says. “But this maggot work and getting the bad guys off the street is the neatest.”

Number 8: Olympic Drug Tester

When your job is drug testing the world´s top athletes, there´s no way to win

Every two years, the athletes of the world light a torch, gather together, and cheat like crazy. To combat the inevitable underhandedness at the 2008 Beijing Games, dozens of officers at doping-control stations will watch jocks urinate into cups about 4,000 times over 21 days. And even then, testers will still find themselves in a lose-lose situation. If they catch a cheat, they anger an entire nation. If they don´t nab a cheat who later tests positive, they´re berated in the media for incompetence. And even their most sophisticated tests are probably missing the big sins. That´s because in the arms race to make performance-enhancing drugs more powerful and less detectable, the dopers are winning. “By the time a drug is known to testers, it´s often pass,” explains University of Western Ontario bioethicist Kenneth Kirkwood. “Coaches and team doctors scour scientific literature to find cutting-edge therapies and experimental drugs,” he says. “The testers don´t even know what to look for.”

Number 7: Gravity Research Subject

They´re strapped down so astronauts can blast off

Spend time in outer space, and the lack of gravity will earn you the bloated look astronauts call puffy face, as well as atrophied muscles and bone degeneration. Researchers hope to combat these symptoms by developing artificial-gravity therapies for long voyages. But the only way to approximate the effects of weightlessness is by having volunteers lie still-for weeks on end.

Liz Warren, a researcher at the NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston, managed to convince 15 men to spend 21 straight days in bed. They were tilted head-down at a 6-degree angle, which, along with their inactivity, mimicked the restricted muscle use and increased blood flow to the head experienced in space. The subjects showered using handheld hoses, relieved themselves in bedpans, and were occasionally wheeled out to a common area to socialize with other bedridden guinea pigs.

What´s more, every day technicians strapped the subjects to a gravity-simulating centrifuge and slung them around for an hour, creating 1 G near their hearts and 2.5 Gs at their feet. Their vitals were then compared with subjects who had skipped the ride.

For actor Tim Judd, it was a life-changing experience; the $6,000 payday gave him enough cash to move to Los Angeles to pursue his film career. It´s a good thing he had such a strong motivation. “Your body cavity is upside down, and after the first day you can feel your internal organs start to shift toward your head,” he says. Although Warren´s study is now complete, NASA is still far from a full understanding of how to mitigate the effects of weightlessness. “We´ve got a whole wing at the University of Texas hospital in Galveston,” Warren says, “and it´s always full of NASA bed-rest subjects.”

Number 6: Microsoft Security Grunt

Like wearing a big sign that reads “Hack Me”

Do you flinch when your inbox dings? The people manning secure@microsoft.com receive approximately 100,000 dings a year, each one a message that something in the Microsoft empire may have gone terribly wrong. Teams of Microsoft Security Response Center employees toil 365 days a year to fix the kinks in Windows, Internet Explorer, Office and all the behemoth´s other products. It´s tedious work. Each product can have multiple versions in multiple languages, and each needs its own repairs (by one estimate, Explorer alone has 300 different configurations). Plus, to most hackers, crippling Microsoft is the geek equivalent of taking down the Death Star, so the assault is relentless. According to the SANS Institute, a security research group, Microsoft products are among the top five targets of online attack. Meanwhile, faith in Microsoft security is ever-shakier-according to one estimate, 30 percent of corporate chief information officers have moved away from some Windows platforms in recent years. “Microsoft is between a rock and a hard place,” says Marcus Sachs, the director of the SANS Internet Storm Center. “They have to patch so much software on a case-by-case basis. And all in a world that just doesn´t have time to wait.”

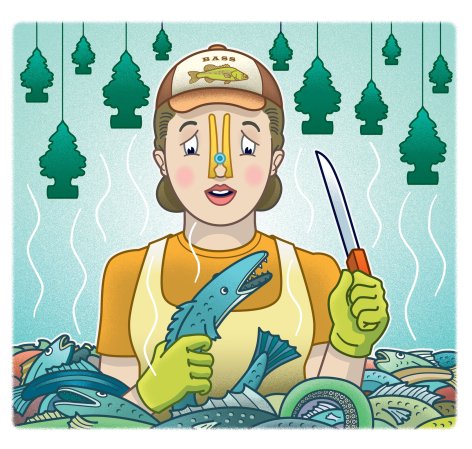

Number 5: Coursework Carcass Preparer

They kill, pickle, and bottle the critters that schoolkids cut up

Remember that first whiff of formaldehyde when the teacher brought out the frogs in ninth-grade biology? Now imagine inhaling those fumes eight hours a day, five days a week. That´s the plight of biological-supply preparers, the folks who poison, preserve, and bag the worms, frogs, cats, pigeons, sharks and even cockroaches that end up in high-school and college biology classrooms.

At Ward´s Natural Science in Rochester, New York, one of the nation´s largest suppliers of coursework carcasses, an 18-member crew processes dozens of species every year. Insects like fleas and cockroaches are the easiest, according to Jim Collins, the interim supervisor in the company´s preserved-materials department. They´re simply preserved in jars of alcohol. The pigeons and frogs, though, come live from collectors and breeders and must be euthanized on-site (usually in a CO2 chamber for the pigeons and immersion in benzicane, a chemical used to treat tooth pain, for the frogs). Once the deed is done, workers embalm small corpses and inject colored latex into their arterial and venous systems to make identification easier for the kids. Then the specimens are packed in 55-gallon drums to cure for a few weeks before they´re ready for the dissecting table. Collins and his team aren´t put off by the job, although the lab does have a high dropout rate. “We have people who come in and work for a day or two and then say they can´t do it,” Collins says. “But most of us enjoy the work.”

Number 4: Garbologist

Think Indiana Jones–in a Dumpster

Archaeologists usually pick through ancient garbage. But William Rathje of Stanford University won´t wait. Since 1973 the self-termed “garbologist” has sifted through at least 250,000 pounds of refuse to analyze modern consumption patterns and how quickly waste breaks down. He typically drills 15 to 20 “wells” to the bottom of a landfill, some 90 feet deep, and pulls 20 to 30 tons of material from each well, which he and his students then catalog. What he´s learned: Dirty diapers make up less than 2 percent of landfills, while paper accounts for 45 percent. Hot dogs can last up to 24 years in a dump, and there is a correlation between cat ownership (litter) and National Enquirer readers (discarded copies). Rathje looks at other trash, too. One project involved scouring garbage cans in Tucson, Arizona, cataloging candy wrappers and used dental floss, toothbrushes and toothpaste tubes to compare survey claims about dental health with reality. The conclusion: There´s far more junk out there than ways to get it off your teeth.

Number 3: Elephant Vasectomist

When your patient is Earth´s largest land animal, sterilization is a big job

What´s one foot across and sits behind two inches of skin, four inches of fat and 10 inches of muscle? That´s right: an elephant´s testicle. Which means veterinarian Mark Stetter´s newest invention—a four-foot-long fiber-optic laparoscope attached to a video monitor—has to be a heavy-duty piece of equipment to sterilize a randy bull pachyderm.

Stetter, the head doc at Disney´s Animal Kingdom in Florida, created the device to help control elephants in African wildlife parks, where the jumbos have been breeding too quickly and eating up more than their share of the surrounding habitat. The snipping began last summer when Stetter and his team field-tested the device on four unsuspecting bulls at the Welgevonden Private Game Reserve in South Africa. After a pachyderm was sedated with a dart from a helicopter, the team used a crane truck to pull the sleeping beast upright. Four-inch incisions were made, and the laparoscope was inserted into the abdomen near the reproductive organs (an elephant´s testicles are on the inside, like ovaries). When he located the centimeter-thick vas deferens-the tube that carries semen from the testicles to the penis-Stetter inserted a long pair of scissors through the scope and cut out a two- or three-inch section.

So far, the method seems to be working. The first four test subjects survived the ordeal with no complications (except the possibility of bruised pride). If things go the way Stetter plans, elephants throughout southern Africa will soon be crossing their legs in fear: He has begun training other field vets to perform the procedure, and hopes to have multinational trials up and running soon.

Number 2: Oceanographer

Nothing but bad news, day in and day out

Scientists estimate that overfishing will end wild-seafood harvests by 2048 and that Earth´s coral reefs will be rubble within decades. About 200 deoxygenated “dead zones” dot the world´s coasts, up from 149 in 2004. Meanwhile, a vortex of plastic the size of Texas clogs the North Pacific, choking fish and birds; construction is destroying coastal habitats; and countless key marine species are nearly extinct. To top it all off, if global warming goes the way scientists predict, the uptick of carbon dioxide levels in the seas will acidify the water until little more than jellyfish can live there.

With so much going on, there´s plenty of work for oceangoing scientists-if they can stomach bad news. Carl Safina, the founder of the nonprofit Blue Ocean Institute, is proud of the work he´s done to battle overfishing in the U.S., where some species are actually on the mend. Nevertheless, he says, humans are “poised to remake the ocean into a new kind of environment”-one that might require a toxic-containment suit. Recently, Ron Johnstone, an Australian marine biologist, broke out in boils while studying sediment. He was poisoned by fireweed, a toxic cyanobacteria exploding across the globe in response to pollution.

Number 1: Hazmat Diver

They swim in sewage. Enough said.

“The worst was at a factory pig farm,” says Steven M. Barsky, the author of Diving in High-Risk Environments, the industry bible for hazardous-materials divers. “A guy had driven his truck into the waste lagoon and drowned. Not only was it full of urine and liquid pig feces, the farmer had dumped all the needles used to inject the pigs with antibiotics and hormones in there.” Someone had to recover the body, and the task fell to commercial hazmat divers.

Outfitted with fully encapsulating drysuits, these Jacques Cousteaus of the sewers swim into clouds of waste, inside nuclear reactors and through toxic spills on America´s coasts and inland waterways. When the Environmental Protection Agency identifies pollutants, it contracts with a hazmat team to clean things up. That means using giant vacuums to suck up a polluted lakebed, hoisting leaking barrels to the surface, or diving into the heart of an oil spill or into a sewer to fix a clog. It´s dangerous work-one breach in the drysuit, and a whole stew of bacteria and toxins can fill ´er up. Jesse Hutton, of Ballard Salvage and Diving in Seattle, has seen his share of close calls. “I´ve been on jobs where suits have been breached by rough steel or something sharp,” he says, pointing out that divers must keep their shots up to date.

The divers are generally well-paid, but hey, so are accountants. “To be an expert,” Barsky says, “you need to be a chemist, a physician, a biologist and 10 other things. Not many people are.”