The title of “astronaut” is one of the rarest designations a human can have—only 652 people on our planet have ventured into outer space.

Figuring out how to leave Earth on a rocket was truly such a difficult task that it required resources and manpower that only a government-scale operation like NASA could provide. And in the early days of the space race, only experienced military pilots (mostly white men) were accepted into NASA’s astronaut ranks, drastically restricting who had a chance to go to space in the U.S.

In the past few decades, however, the landscape of spaceflight has changed significantly. NASA is no longer the sole manager of U.S. space travel, and many private companies—SpaceX, Blue Origin, Virgin Galactic, and more—have now successfully launched humans into space. Some of these companies claim their goal is to make space travel more accessible to the public, but it’s still a unique and rare opportunity to join one of these missions. So, who actually gets to be an astronaut nowadays?

When most Americans think of an astronaut, images of rigorously-trained and ridiculously impressive NASA employees doing spacewalks probably come to mind. Since the 1980s, with the dawn of the space shuttle program, NASA missions have included not only military pilots, but also mission specialists whose expertise was in some form of science or engineering. Nowadays, NASA astronaut applications are open to all who meet the basic requirements: U.S. citizenship, a master’s degree in STEM, three years of professional experience post-degree, and the ability to complete a physical.

[ Related: How to apply to be a NASA astronaut ]

Being a NASA astronaut is a full-time job—but, even back in the 1980s, a handful of people who weren’t professional astronauts made it into space on the shuttle. For example, Utah Senator Jake Garn flew aboard space shuttle Discovery in 1985, and Florida Congressman Bill Nelson (better known for his more recent role as NASA Administrator) went the following year on space shuttle Columbia. Both Garn and Nelson were important figures in the government committees that oversaw NASA’s budget and activities.

The space shuttle flights, however, were still strictly part of NASA’s domain. The first non-NASA-sponsored American trip to space wasn’t until 2001, when investment firm founder Dennis Tito shelled out a whopping $20 million dollars to go to the International Space Station. His ride came courtesy of the Russian Soyuz program, who worked with U.S. company Space Adventures to sell spots on their missions to whoever could pay. Space Adventures took six more paying customers to the ISS during the 2000s, including an entrepreneur, a video game developer, and a tech billionaire.

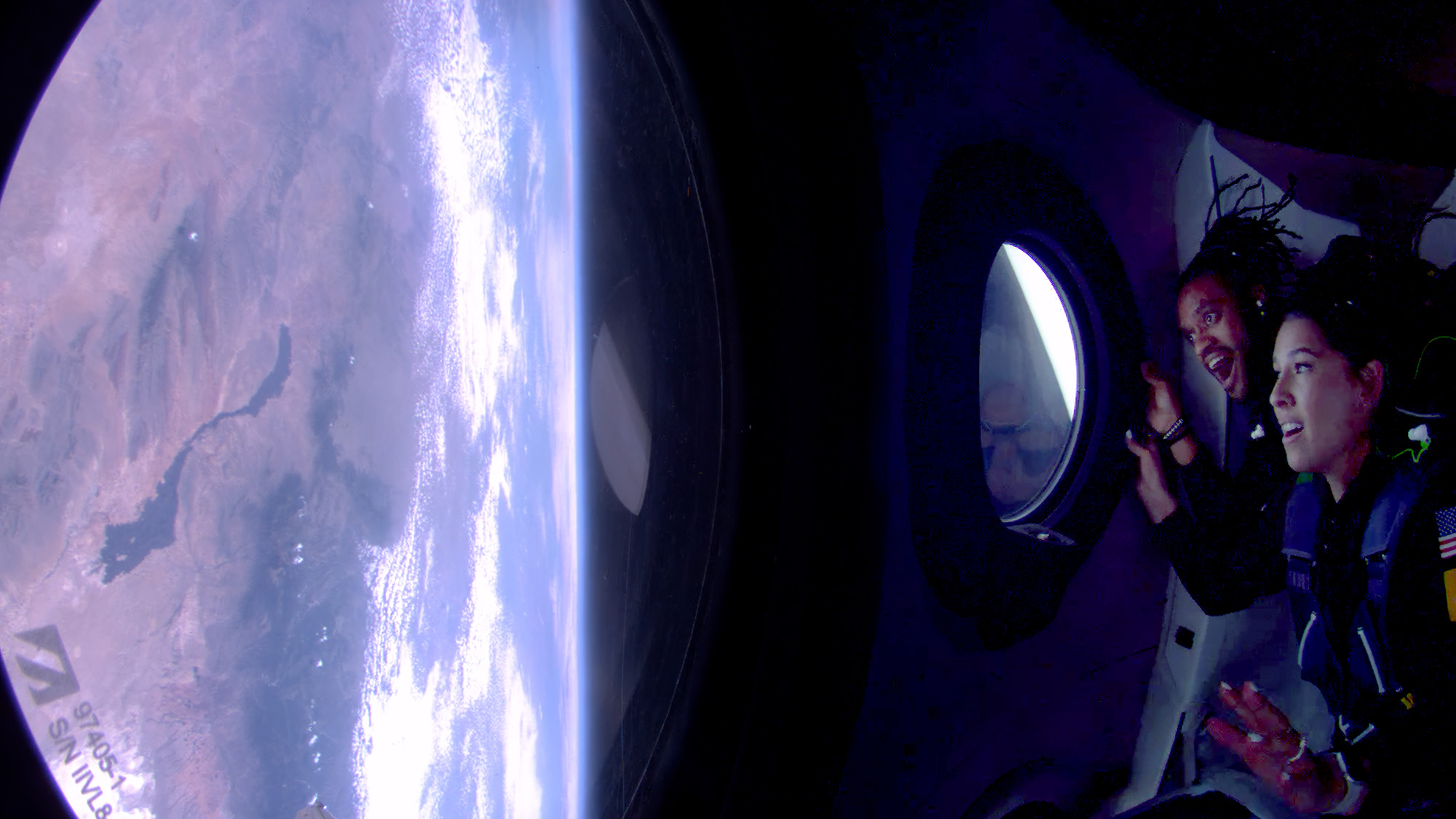

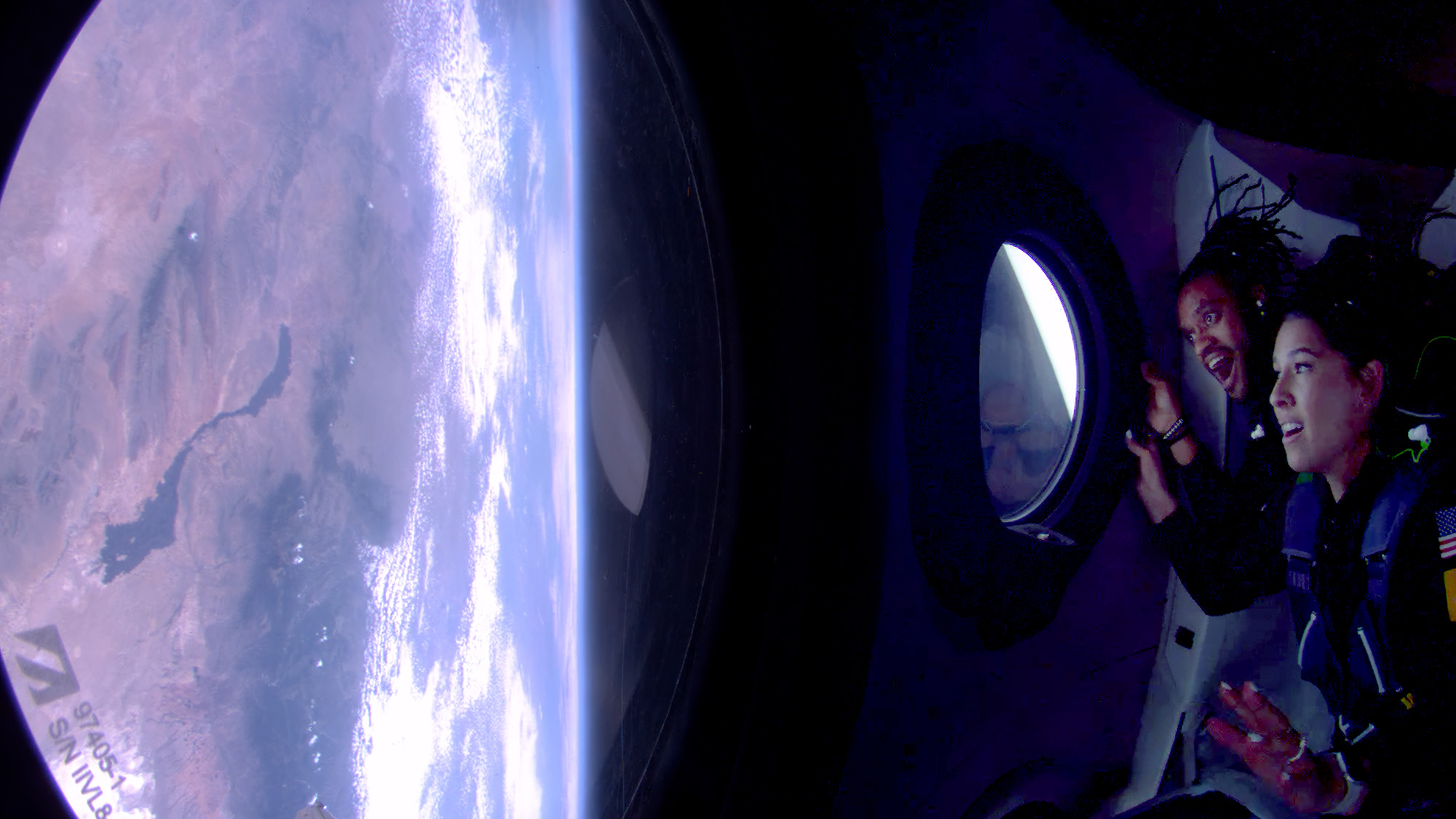

There are still plenty of rich people paying to go to space today—some for only minutes to hours on a quick up and down trip, like Virgin Galactic’s flights, just reaching the agreed-upon boundary of space known as the Karman line 62 miles above sea level. The prices for a seat on Virgin Galactic cost just shy of half a million dollars, and Blue Origin (Jeff Bezos and Amazon’s space endeavor) is pretty secretive about their pricing, seemingly tailoring their costs to what applicants can afford. “Yes, it’s expensive,” said French entrepreneur Sylvain Chiron, who flew with Blue Origins earlier this year, to French news outlet AFP. But it’s “not completely crazy either,” he added. “There are some who would buy a pretty red car with this money.”

If you don’t have the cash, though, there are other ways to get on one of these flights. As these companies ramp up, many private astronauts have been employees of the company managing the launch, there to make sure everything runs smoothly and see how they can improve their tech. On Virgin Galactic, for example, Beth Moses flies as a professional astronaut instructor for the company and Christopher Huie as a senior member of their engineering team.

Others were specifically chosen and sponsored by an organization, such as Hayley Arceneaux, a cancer survivor sponsored by St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital to ride on SpaceX’s Inspiration4, the first all-civilian space mission. Arceneaux’s flight was the first for a pediatric cancer survivor and the first for an astronaut with a prosthetic. A spot on Blue Origin was also recently given to Ed Dwight, America’s first Black astronaut at NASA who never actually got to fly, righting a decades-old wrong.

Scientific organizations have also sponsored sending up their researchers to make new discoveries. Virgin Galactic’s 5th mission in 2023 sent up planetary scientist Alan Stern and science communicator Kellie Gerardi to collect biological data, wearing monitors on themselves to understand the impacts of launch and reentry on our bodies. Their flights were supported by the Southwest Research Institute—as part of a NASA initiative to get researchers into space—and the International Institute for Astronautical Sciences, respectively.

Lastly and arguably the most democratic of the current options, a handful of people have won seats on a ride to space via a competition or philanthropic fundraiser. Inspiration4 offered a spot to Sian Proctor for winning a contest using Shift4Shop, the commerce platform of the mission’s private funder, Jared Isaacman. On that same mission, a seat was given randomly to Chris Sembroski as a donor to a St. Jude fundraiser; similarly, Kiesha Schahaff won two spots on Virgin Galactic from a fundraiser for non-profit Space for Humanity.

Given that most of the astronauts described above flew within the last five years, private spaceflight is just getting started. Flying on an aircraft was a pricey luxury a century ago, and now it’s entirely commonplace—perhaps spaceflight may take a similar path, and slowly become more accessible.