Despite some recent delays, NASA’s Artemis program is still largely on track to establish a permanent human presence on the moon. Artemis astronauts will rely on a lot of logistical information, both while traversing the lunar surface, as well as for the semi-regular traffic to and from Earth. To prepare for this, NASA is testing various tools to ensure a safe, precise, and reliable extended lunar stay for visitors—and one of the space agency’s most successful recent experiments harnessed a long-used tactic here on Earth to achieve a first for the moon.

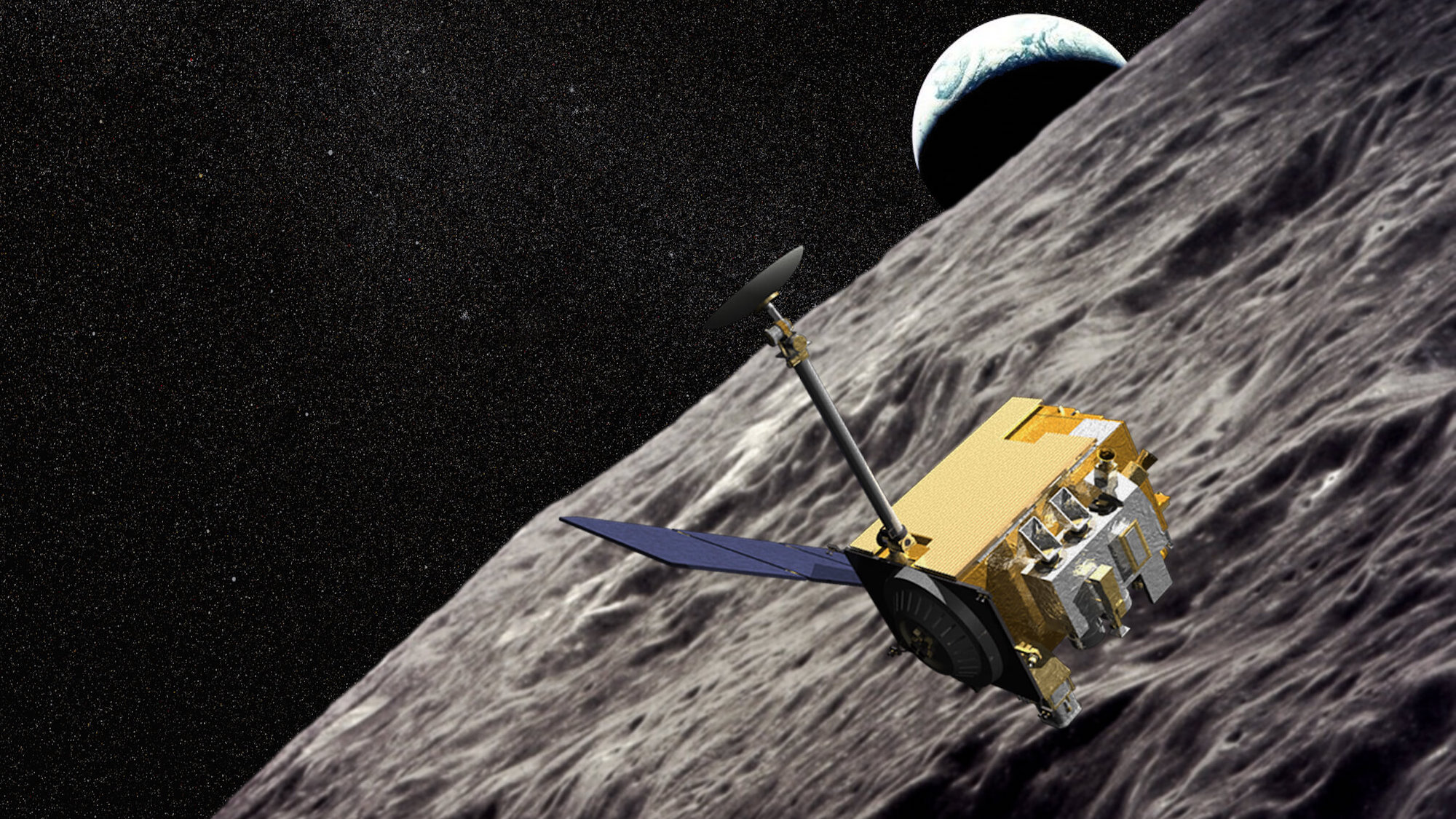

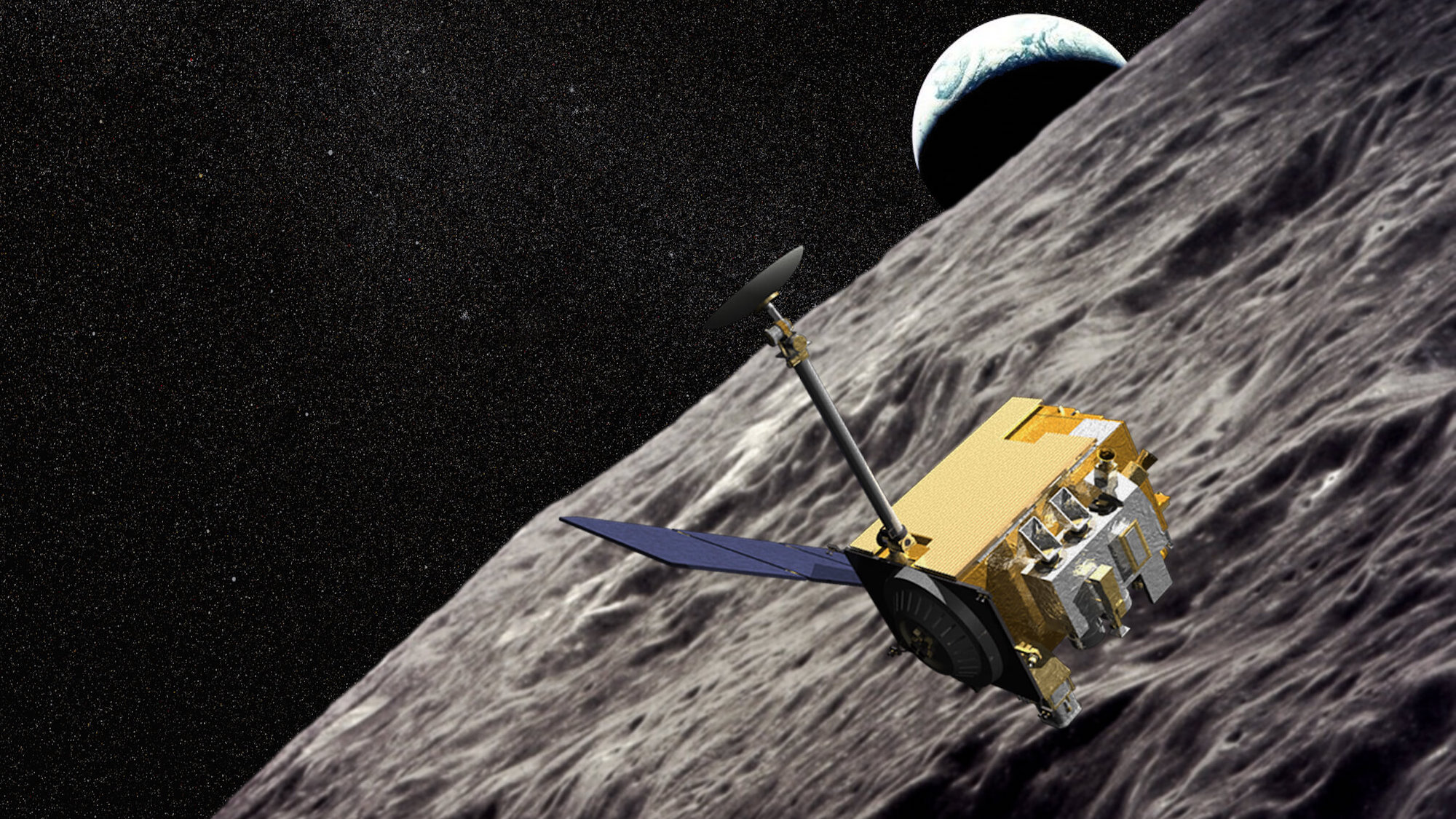

According to NASA, its Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO)—currently in moon’s orbit—recently aimed a laser altimeter approximately 100km (roughly 62 miles) away below at the Indian Space Research Organization’s (ISRO) Vikram lander, near the South Pole region’s Manzinus crater. After firing off a series of five pulses on December 12, 2023, the LRO then recorded the signal mirrored off a small retroreflector aboard Vikram, confirming the method’s first lunar success.

[Related: NASA delays two crewed Artemis moon missions.]

Measuring a laser’s return time from a retroreflector can help accurately estimate an object’s distance and location. Laser altimeters are often utilized to track satellites above Earth, albeit in the reverse of last month’s test; pulses usually fire from equipment on the surface towards orbital satellites, instead of the other way around. Retroreflectors were also used during Apollo missions to measure the moon’s distance from Earth—an expanse revealed to be growing 1.5 inches further every year.

The Apollo missions’ suitcase-sized reflectors were much larger than the one aboard Vikram, however. In comparison, the Laser Retroreflector Array housed on the Vikram lander is just a circular, 2-inch-diameter aluminum framework. No power source is needed to do its job—all it has to do is wait for lasers to bounce off any of its eight quartz-corner-cube prisms back to the beam’s source.

And speaking of waiting, there was quite a lot of it. LRO’s Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter (LOLA) emits pulses that only cover a 32-feet-wide portion of the moon’s surface. Gaps between each pulse ensured only a small chance actually hitting the retroreflector as the LRO traveled over the Vikram lander.

“Altimeters are great for detecting craters, rocks, and boulders to create global elevation maps of the Moon. But they aren’t ideal for pointing to within one-hundredth of a degree of a retroreflector, which is what’s required to consistently achieve a ping,” NASA explained last week. Because of this, it took eight attempts to finally make contact with Vikram.

LRO’s altimeter is currently the only laser tool orbiting the moon, so many more will be needed to ensure consistent, accurate measurement readings from retroreflectors. Once those are in place, however, future laser systems could be used to help Artemis astronauts land in the near total lunar darkness, as well as mark locations of already landed spacecraft. Similar retroreflector arrays are currently employed to help cargo deliveries autonomously dock with the International Space Station. Think of them like tiny lunar air traffic controllers helping direct navigation and safety for astronauts.

Until then, more retroreflectors are on their way—JAXA’s SLIM lander included one during its touchdown last week, and another is scheduled to be aboard a private company’s launch in mid-February.