This article was originally featured on Knowable Magazine.

At the slightest touch of the reins, he felt a familiarity that shook him. It was 2016, and polo player Adolfo Cambiaso — considered the best in the world — was riding for the first time on a genetic clone of Cuartetera, his flagship mare. The same explosive start, the same agility in the curves, the same sustained stride in the long sprints. “It was the same,” he recalls. “Same movements, same head…. I couldn’t believe it.” It took only a few seconds for him to realize that his gamble — which many had dismissed as nonsense — had paid off.

Cambiaso, now 50, had seen before anyone else, back in 2006, the opportunity to preserve the genetics of his most exceptional horses through cloning and thus perpetuate his La Dolfina team, from the province of Buenos Aires, at the top of polo for generations.

That year, in the middle of the Palermo Open final — the ultimate temple of polo — his horse Aiken Cura suffered a devastating fracture and had to be put down. But before saying goodbye, Cambiaso made an unusual request to the veterinarians. “Just in case, before they put him to sleep, I said, ‘Let’s save some cells.’” It was nothing more than a hunch. He had heard the story of Dolly the sheep, the first mammal cloned from an adult cell, and the idea stuck in his mind.

That intuition two decades ago led to a radical change in the world of polo. La Dolfina, now with more than 150 cloned horses, has established unprecedented dominance, and Argentina has become the world center for horse cloning, far ahead of the United States and Europe. Over the years, laboratories have refined the procedure and improved the success rate — although it remains low.

Hence the high costs: Cloning a horse involves far more investment than that required to breed a good specimen the traditional way. And although equine cloning is no longer a rarity but a mature industry, the ethical dilemmas surrounding it — animal welfare, fair competition and the extent to which biology should be manipulated for sporting purposes — still persist.

Making genetic copies of mammals

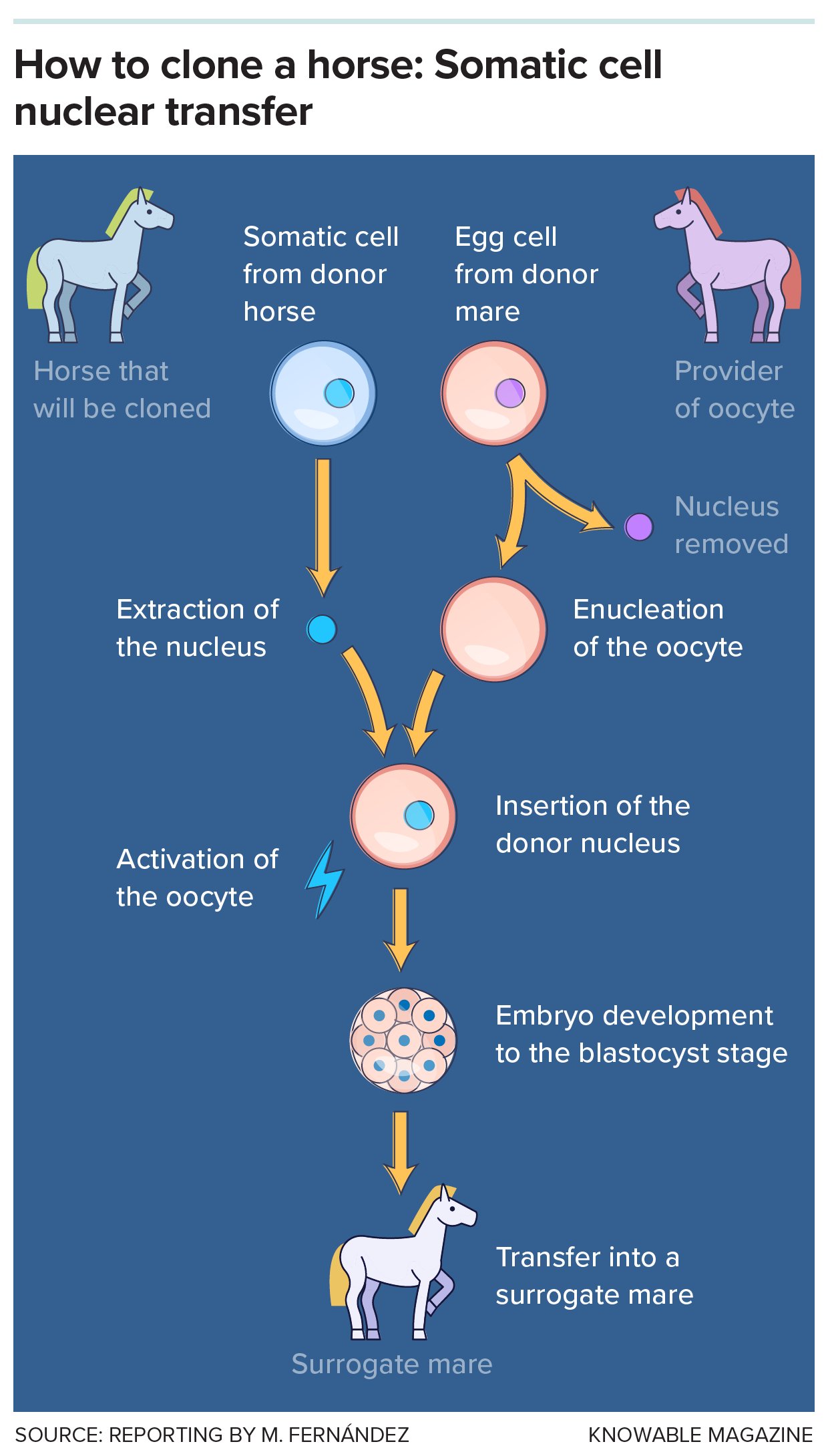

In all mammals, including horses, the cloning process is similar. First, a somatic cell —a nonreproductive cell such as a skin cell — is taken from the animal to be cloned, and its nucleus, which contains the genetic information, is extracted. At the same time, scientists take an egg cell from the same species and remove its nuclear DNA, in a process called enucleation. The nucleus that was extracted from the first cell is then inserted into this “empty” egg cell.

Next, that egg with its new nucleus is stimulated chemically or by electrical impulses to begin dividing and form an embryo. The embryo is cultured in vitro for seven or eight days until it reaches the blastocyst stage, at which point it is implanted in a female who will carry the pregnancy to term.

The method is called somatic cell nuclear transfer. It was used to create Dolly the sheep in 1996, a milestone that proved it was possible to “reset” an animal’s DNA and bring it to an embryonic state capable of development, although with major challenges along the way.

Since Dolly, more than 25 species of mammals have been successfully cloned, including cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, horses, dogs, cats and wild species such as gray wolves and ferrets. The main limitations of cloning lie in the fact that the transferred nucleus does not always manage to reprogram itself completely, and that the mitochondria of the recipient egg and the genome of the transferred nucleus may have incompatibilities, explains Andrés Gambini, a veterinarian specializing in animal reproduction at the University of Queensland in Australia.

Mitochondria are small structures within cells that produce the energy necessary for them to function. They contain DNA of their own, and for this reason clones are not entirely genetically identical to each other. Although they share the same nuclear DNA from the original animal, the mitochondrial DNA will differ because it comes not from the original animal but from the female oocyte that was used in the cloning process. Though its DNA represents a tiny fraction of the total genome, it plays a critical role in the cell, and so those small variations can translate into differences of function and appearance, says Sebastián Demyda Peyrás, an equine geneticist at the University of Cordoba, Spain.

In addition, he says, “epigenetic patterns in cloning are altered much more frequently than in natural pregnancies. Both factors — mitochondrial replacement and epigenetics — influence the higher rate of miscarriages and the number of clones born with health problems, placental abnormalities or severe physical problems.” (Epigenetics refers to the way that genes may be turned on or off due to the addition or removal of small chemical groups, without affecting the DNA sequence itself.)

Despite its technical challenges, cloning has opened the door to many applications, such as species conservation, livestock breeding and even attempts to bring back extinct species. In the field of conservation, genetic material stored in biobanks can be used to reestablish a healthy breeding population, improving genetic diversity and increasing the number of animals that can reproduce, says Aleona Swegen, a reproductive veterinarian at the University of Newcastle, Australia, and coauthor of a 2024 overview of cloning in conservation in the Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. The main challenges, she says, are the need to find an adequate number of oocytes from closely related species and suitable surrogate mothers for gestation.

Cloning also continues to face challenges in domestic animals. A critical moment, different for each species, is when the embryo stops relying on RNA and proteins from the maternal egg and begins to use its own DNA, says Pablo Ross, chief scientific officer at STgenetics, a global leader in bovine reproductive biotechnology, and an animal geneticist at the University of California, Davis. In cattle, this step, known as embryonic genome activation, occurs when the embryo has between eight and 16 cells, while in horses it occurs when it has four to eight cells.

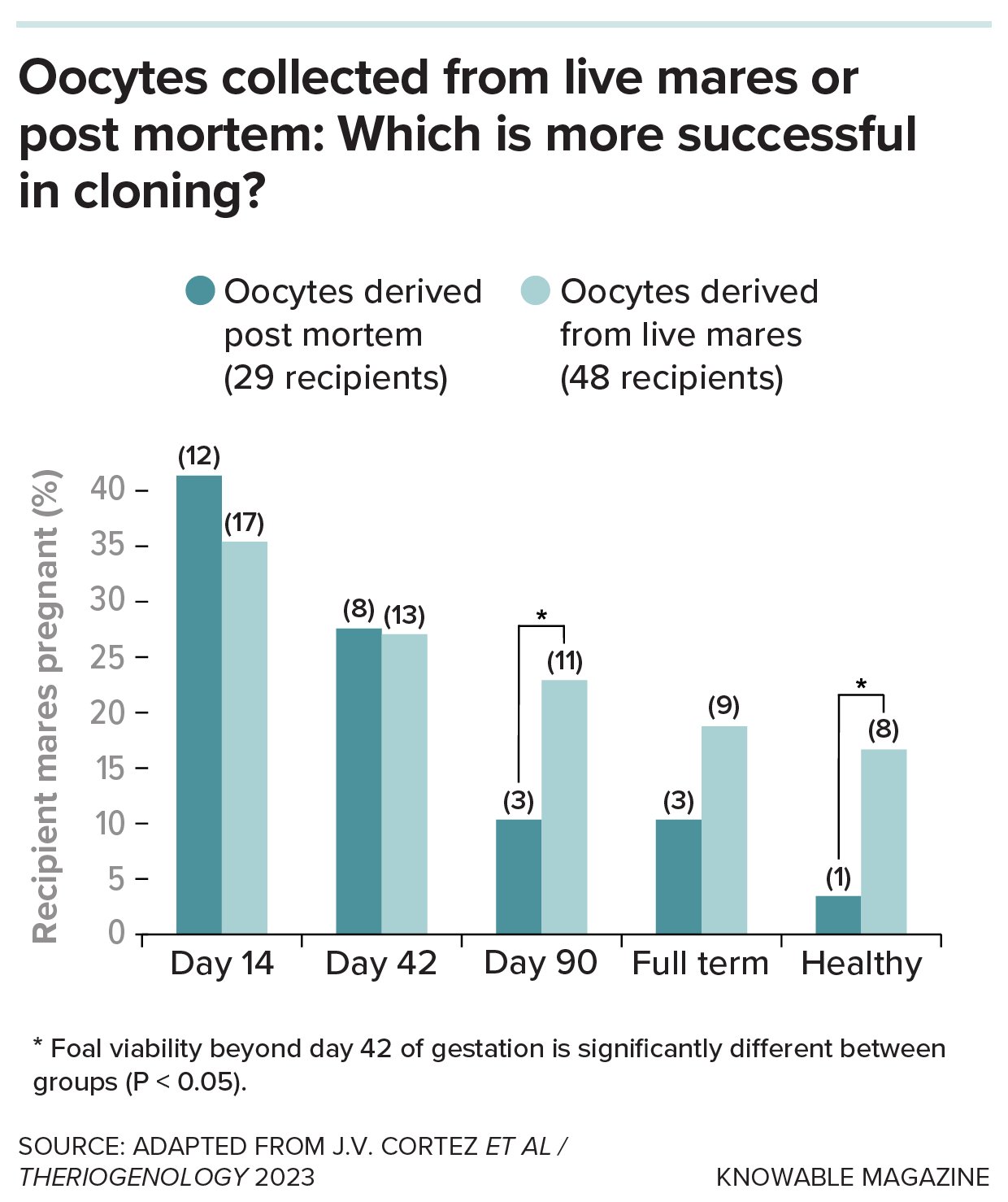

In horses, as in other species, public protocols for cloning already exist, but success depends on the expertise of the team and technical details that are not always included in manuals. A critical issue in horses is the source of the oocytes. One alternative is to obtain them from the ovaries of dead mares collected at slaughterhouses, although they can also be extracted from live females by transvaginal aspiration, a more invasive procedure but with better success rates.

With oocytes obtained using transvaginal aspiration, the proportion of embryos that reach the blastocyst stage is around 35 percent, compared to just 26 percent in oocytes obtained from slaughterhouses. And the difference widens in later stages: Among mares that remain pregnant after day 42, just over half of pregnancies derived from eggs obtained by transvaginal aspiration result in healthy foals, compared to just one in 10 when the eggs come from slaughterhouses.

In recent years, several advances have improved horse cloning, says Flávio Vieira Meirelles, a reproductive biotechnologist at the University of São Paulo, Brazil. These mainly involve methods for activation of the egg after inserting the nucleus, and cultivation conditions for the embryo. In addition, the efficiency with which the genes of the donated nucleus are reprogrammed — a process that is carried out by chemicals in the cytoplasm of the egg — has improved.

Greater success, too, is achieved when the donated nuclei come from adult stem cells — which are capable of renewing themselves and transforming into various tissues within an organ — compared with nuclei from fully differentiated cells from a tissue such as skin. The differentiated cells carry more “memory” of their original function. Also, cells from young animals tend to respond better than those from older animals. And, of course, the reproductive capacity of the female surrogate mothers plays a role, too. Even with everything optimized, the birth rate per transferred embryo is low in large mammals, ranging from 3 to 10 percent.

Despite the difficulties, cloning has expanded and today fuels an industry as diverse as it is disturbing: Exceptional cattle are cloned to produce high-quality meat, companion animals are cloned for owners who are unable to say goodbye to their pets (and are willing to invest $50,000 in a clone of their dog or cat), and extraordinary polo horses are cloned to try to ensure victory on the field.

Argentina: Epicenter of horse cloning

In 2010, while completing his doctoral thesis on cloning at the University of Buenos Aires, biotechnologist Gabriel Vichera came across a news story that shook him: Adolfo Cambiaso had auctioned off one of the clones of his star mare, Cuartetera, for an eye-watering $800,000. It was the first time that a cloned animal bred for high athletic performance had been presented as a high-value asset, and in a market where polo horses can be worth anywhere from $50,000 to nearly $1 million for extraordinary specimens, the sale made it clear that there was money waiting to be made.

That clone of Cuartetera had been created in the United States. Vichera wondered if he could bring the technique to Argentina and scale it up. At that time, the University of Buenos Aires had the technology to perform cloning, and a favorable ecosystem to carry out the work was beginning to form in the country. Polo, with horses valued as works of art and team owners obsessed with preserving winning genetics, seemed like the perfect terrain to explore. “Planning to clone these exceptional horses represented a huge business opportunity,” says Vichera.

Even as the news of Cuartetera sparked both amazement and controversy due to ethical concerns about manipulating animals for sporting purposes, Vichera, along with two partners, founded a company to optimize and standardize the cloning process and make it a common tool in professional polo.

At first, the results were not encouraging. The first clones by Vichera’s company, Kheiron Biotech, between 2012 and 2016, were made from adult skin cells, and almost half of the foals from the 38 live births had abnormalities of the umbilical cord or placenta, or limbs that were abnormally bent. The turning point came when the company started working with stem cells from bone marrow. “This technology changed everything. Today, almost 100 percent of births are as healthy as those obtained through natural breeding,” says Vichera. To date, Kheiron Biotech reports having produced a thousand cloned horses.

With the cloning technique now mastered, Kheiron Biotech ventured into even more ambitious territory. In December 2024, the company announced the birth of five foals that had been genetically edited using the CRISPR-Cas9 technique, a global milestone in equine breeding. The intervention consisted of inserting a DNA sequence known as SINE into the control sequences of the creatures’ myostatin gene. This is a genetic variant that already exists naturally in some breeds and influences muscle development. The main goal, however, was to demonstrate that precision genetic editing in horses is technically feasible, and compatible with cloning,

Vichera presented the achievement as proof of concept and a preview of a scenario in which it will be possible not only to copy the best horses, but also to introduce specific modifications to their genomes. Editing the myostatin gene has known effects on muscle fiber composition and performance during short, intense efforts, and there is ongoing research into other genes and possible applications, although the details have not been revealed.

With polo as its flagship, Argentina overwhelmingly dominates the global equine cloning industry, followed — at a considerable distance — by the United States and some European countries.

But despite the technical advances, significant losses occur at each stage. It is estimated that, out of every 100 embryos, 20 reach the blastocyst stage and are transferred. Of these, 10 are successfully implanted in surrogate mares, and of those 10, only five reach full term. Even among foals born, there can be problems with health and development, although the lack of public data prevents this from being quantified accurately.

The high loss rate partly explains the high cost of the procedure. Although the price has fallen in recent years thanks to technical advances, cloning a horse remains a luxury: It costs around $40,000 per born animal.

Cambiaso’s dream come true

Shortly after Cambiaso requested that tissue from his horse Aiken Cura be preserved following the animal’s devastating fall and euthanasia, he launched Crestview Genetics, founded with Texas oilman Alan Meeker and Argentine businessman Ernesto Gutiérrez. In Texas, the company partnered with the firm ViaGen to begin the cloning work.

In August 2010 — four years after the accident that killed Aiken Cura — Cambiaso was in Santa Barbara, California, when he received a call with the news that the first clones of Aiken Cura and those of his mare Cuartetera had been born. He traveled immediately to see them. “It was a strange feeling,” he recalls. “We spent two hours looking at them, unable to believe it.”

Fabricio García, one of Argentina’s leading dressage experts, worked with these first young clones. “For me, it was the same as breaking in a normal colt. My boss [Cambiaso] told me, ‘Do your training, I like your training.’ The pressure was on, because they were the first clones, but then I realized they were horses like any other,” he says.

Training is the basis of everything, adds García, like the foundation of a house. As the years go by, the colt gets used to contact with the saddle and reins. Then it is guided through turns, stops and starts until it learns to respond precisely to the rider’s commands. In general, horses are ready to compete at six years of age, but the Cuarteteras — all clones — started with an obvious genetic advantage that allowed them to jump onto the field earlier.

The final of the 2016 Palermo Open would leave an unforgettable image. The original Cuartetera had retired a year earlier, but on the field, lined up by Cambiaso, were six identical mares — chestnut, slender, with a distinctive white spot illuminating their foreheads, all clones of Cuartetera — who would bring victory to La Dolfina. For the first time, clones were playing polo. Their names: Cuartetera B01, Cuartetera B02, Cuartetera B03, Cuartetera B04, Cuartetera B05, and Cuartetera B06.

That image — six cloned mares deciding the most important tournament in world polo — sparked a debate off the field. As equine cloning ceased to be an experimental rarity and became a competitive tool, ethical questions intensified: about the morality of standardizing of animals, and the biological costs of the process, especially for the recipient mares.

“We can talk about identity in any individual, even cloned horses,” says Finnish philosopher Häyry Matti, who specializes in ethics. “Improving the athletic performance of a nonhuman for human entertainment is repugnant. It intensifies objectification, manipulation and hegemonic imposition.”

Indeed, in the daily practice of cloning, dilemmas about animal welfare and objectification translate into procedures and risks that are rarely visible to the public and for which there are often no public records. According to equine geneticist Demyda Peyrás, “many clones are not born in the field, but in specialized veterinary hospitals or in the companies’ own neonatal units due to frequent complications during birth.” These, he adds, are rare in traditional horse breeding.

The ethical debate surrounding equine cloning has changed over the years. In the beginning, the main concern revolved around the health of the clones: malformations and potential suffering during gestation and adulthood. With technical advances and the standardization of protocols, these objections lost their centrality and, at least in the field of polo, the practice began to enjoy relative acceptance. However, this normalization did not dispel all worries. Concerns remain about the actual rate of miscarriages, health problems in foals born and, above all, the lack of transparency and public data to assess the biological impacts of the process.

Pablo Ross, scientific director of STgenetics, argues that today, cloning does not differ substantially from other reproductive technologies applied in animal breeding. Demyda Peyrás, on the other hand, warns of the risk of inbreeding depression, the loss of genetic variability when crossing individuals that are too closely related. The cloning industry relies almost exclusively on lines of the “Polo Argentino” breed and racehorses. If this trend continues, it could have an impact on the fertility and resilience of animals, and their ability to tolerate stress.

In turn, the combination of cloning and gene editing opens up new dilemmas, says Gambini, the University of Queensland veterinarian who specializes in reproductive biotechnologies. It is one thing to use such tools to prevent disease or improve production efficiency — which could be justified on welfare grounds — and quite another to use them to enhance athletic performance for human entertainment. The risks of editing, such as unwanted health effects on the animals, are still uncertain, which is why geneticists like Demyda Peyrás agree on the value of international regulations and the need for mandatory and detailed reporting systems on the development and health of genetically modified animals.

For his part, Cambiaso has always been impervious to questioning. From day one, he has defended a utilitarian view. He sees no ethical dilemmas and justifies the practice because of the benefits it brings to his game. He is driven by sporting glory and the consolidation of an industry that he himself started — an industry operating without public reporting systems that this year recorded the birth of 600 to 700 cloned horses in Argentina alone and has already cloned 60 Cuarteteras.

Article translated by Debbie Ponchner

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, an independent journalistic endeavor from Annual Reviews. Sign up for the newsletter.