Multiple ancient and extinct species of tardigrades, aka “water bears,” can now be seen in unprecedented, high-resolution detail thanks to high-powered microscopy tools. With these new observations, researchers believe they have helped resolve some of the many lingering mysteries within the history of these tiny invertebrates.

Tardigrades are some of the most resilient and oldest creatures on Earth. Experts believe the micro-animal’s earliest ancestors can be traced as far back as 500 million years ago to the Cambrian Period. Meanwhile, today’s tardigrade species likely first evolved between 155-and-66 million years ago next to their (much larger) dinosaur counterparts during the Cretaceous Era.

What sets today’s over 1,100 tardigrade species apart from almost every other animal on the planet is their ability to undergo cryptobiosis. If necessary, water bears excrete all the water in their bodies while slowing their metabolism down to a near-standstill, entering what is known as a tun state. At the same time, these close relatives of arthropods produce a protein that protects their DNA during the extreme hibernation periods often lasting years at a time. They have shown themselves perfectly capable of withstanding outer space’s harsh, radiation-laden environment, existing at the bottom of the ocean near boiling hot volcanic vents, surviving in the Arctic, and even getting shot out of a high-speed gun.

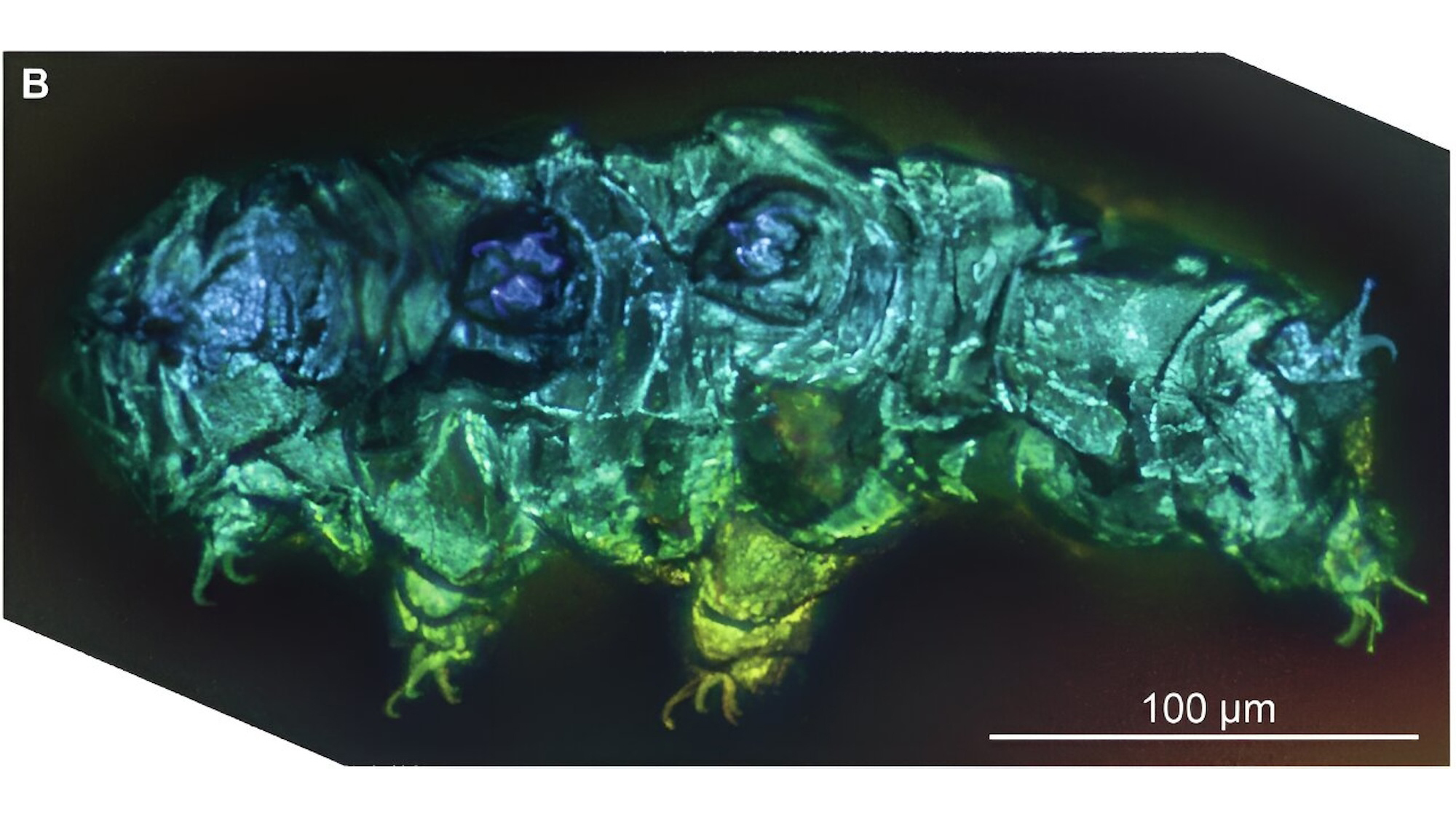

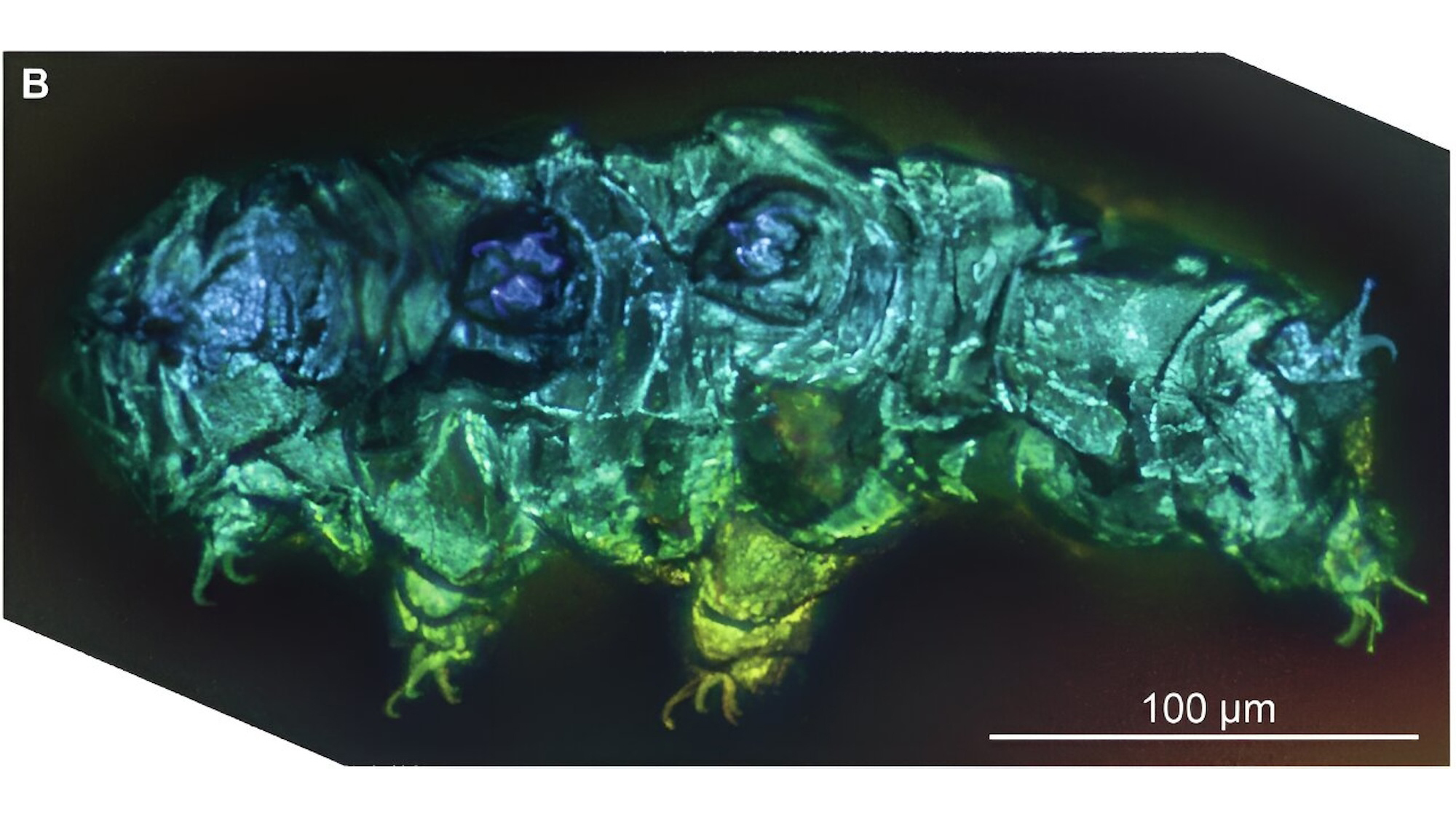

How and when tardigrades evolved to be so tough, however, is still not fully understood by paleobiologists. To help investigate this problem, three evolutionary biologists at Harvard University’s Museum of Comparative Zoology borrowed a chunk of 72-83 million-year-old amber containing two tardigrade fossils. Although the amber has spent decades at Harvard’s museum, researchers have so far spent very little time examining them due to its opaque color, the fossils’ size, and technological limitations.

[Related: How super resilient tardigrades can fix their radiation-damaged DNA.]

After mounting the specimen to a slide using dental wax, the team placed glycerin on each side for the field of view of a confocal fluorescence microscope. A series of photographic “slices” of the tardigrades were then blended together to create high-definition composite images.

The two ancient tardigrades belonged to separate species, Beorn leggi and Aerobius dactylus, both of which have long since gone extinct. That said, their physical characteristics offered the evolutionary biologists never-before-seen details about their commonalities with two families of today’s water bears. After estimating where the two fossilized species were located in the overall tardigrade family tree based on physical characteristics and detailed dating methods, the team were able to “explore the implications of using them for estimating the divergence times of major tardigrade groups.”

In particular, comparisons between the amber fossils and modern tardigrades allowed the team to also determine that at least two separate groups of water bears evolved cryptobiosis at distant points in the past—one between 175 and 430 million years ago, and another between 175 and 382 million years ago.

The team is now also confident that Beorn leggi and Aerobius dactylus belong to the same superfamily group, Hypsibioidea, which offers a “critical fossil calibration point to investigate tardigrade origins.” According to researchers, this important evolutionary linkage and shared development of cryptobiosis “could be one of the factors that have helped [tardigrades] evade extinction” entirely.

Unfortunately, Beorn leggi and Aerobius dactylus are two of the four tardigrade fossils ever discovered, meaning evolutionary biologists still don’t have a lot of material to work with when it comes to the water bears’ evolutionary journey. Still, with advancements like confocal fluorescence microscopy, experts are readier than ever to give them a look once more are found.