The journal Nature, ever the forward-looking publication, is finished with all of this best-of-the-last-decade nonsense. To celebrate the dawn of a new decade, the editors tapped experts across the scientific community, asking them simply “where will your field be ten years from now, and how will we get there?” Our favorite five predictions are collected below.

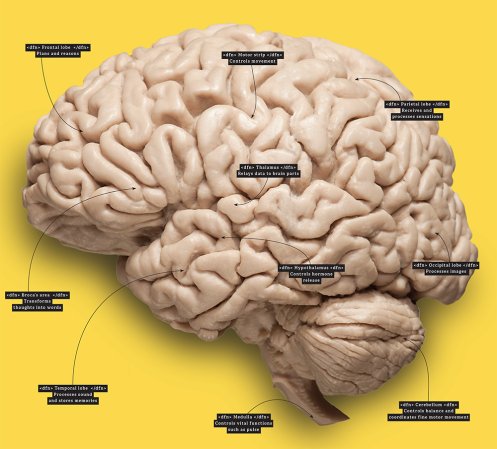

SEARCH

Search is only ten years old, says Google’s Director of Research Peter Norvig. So imagine what it’s going to be like when it’s twice the age it is today. “The majority of search queries will be spoken, not typed, and an experimental minority will be through direct monitoring of brain signals.” But while the thought of beaming movie times and YouTube vids directly to the brain is incredible, the obstacles search faces in the next decade are the same fundamental ones it faces today. Google and its comrades/competitors need to refine search to measure quality and accuracy rather than just popularity, Norvig says. Agreed.

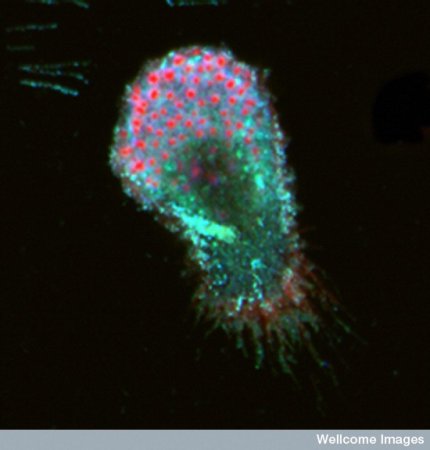

BIOLOGY

David A. Relman, Chief of Infectious Diseases at Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System, thinks medical research will turn away from the processes of the human body, about which we know much, and focus on the microbial processes that occur inside the body, of which we know very little. The various microbes that live and function within our own biology carry out some amazing science all by themselves, and learning about these microbial habitats could lead to myriad breakthroughs. Only by understanding how these ecosystems within us keep us healthy — and make us unhealthy — can we move toward a state of better overall health.

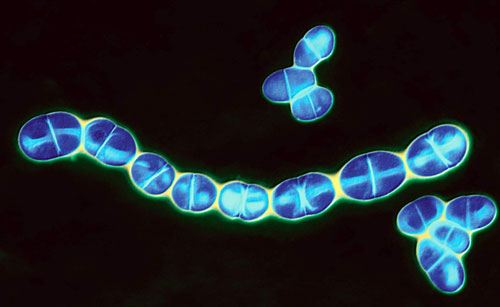

SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY

“The challenge for the next decade will be to integrate molecular engineering and computing to make complex systems,” says George Church, a professor of genetics at Harvard Med. By integrating great advances in computing power to biological processes, we can deliver drugs more effectively, engineer crops, cure cancer and engineer bacteria to carry out our bidding. We can even change the normal course of economic development in depressed nations. Synthetically engineering parasite-resistant crops or photosynthetic organisms that churn out biomass, we can alter the economic landscape. “As costs drop, such technology will allow developing nations to leapfrog fertilizer-wasting, fossil-fuel-intensive and disease-rife farming for cleaner, more efficient systems, just as they are leapfrogging costly landlines in favour of mobile-phone networks.”

LASERS

“Like the inventors of 1960, we are probably still underestimating the full potential and impact of lasers,” say Thomas M. Baer of Stanford and Nicholas P. Bigelow of the University of Rochester. As with everything, the future of lasers is size, and by that we’re talking about the nano scale. Lasers with apertures no bigger than a single molecule will revolutionize everything from genome sequencing to hard disks, which could hold petabytes on a single PC. Even cosmology and physics will be upended. Lasers will measure drift in fundamental constants in the universe, create forms of matter found only at the heart of stars and possibly even create fusion reactions that could provide limitless, non-carbon energy. Not bad for a decade’s work.

RESEARCH

But how do we get this all done? Richard Klausner of the Column Group and David Baltimore of the California Institute of Technology have perhaps the most radical — and amazing — vision for the next decade. It starts at the National Institutes of Health but calls for a change in the culture of how we treat science. When it comes to doling out funding, they argue, we need to focus on the researcher, not the research. The best way to make creative breakthroughs is to fund creative people. Awarding risk-takers rather than good grant writers will fuel a new generation of scientists working on the kind of outside-the-mainstream ideas that landed America on the moon. As such, “we should be encouraging new generations of independent scientists to begin productive careers by aiding their development outside the usual academic routes.” Take our youngest, freshest, most open minds out of the grad student-doctoral student-post doctoral hierarchy that keeps them tethered to the old ideas of their elders? Radical indeed — and we like it.