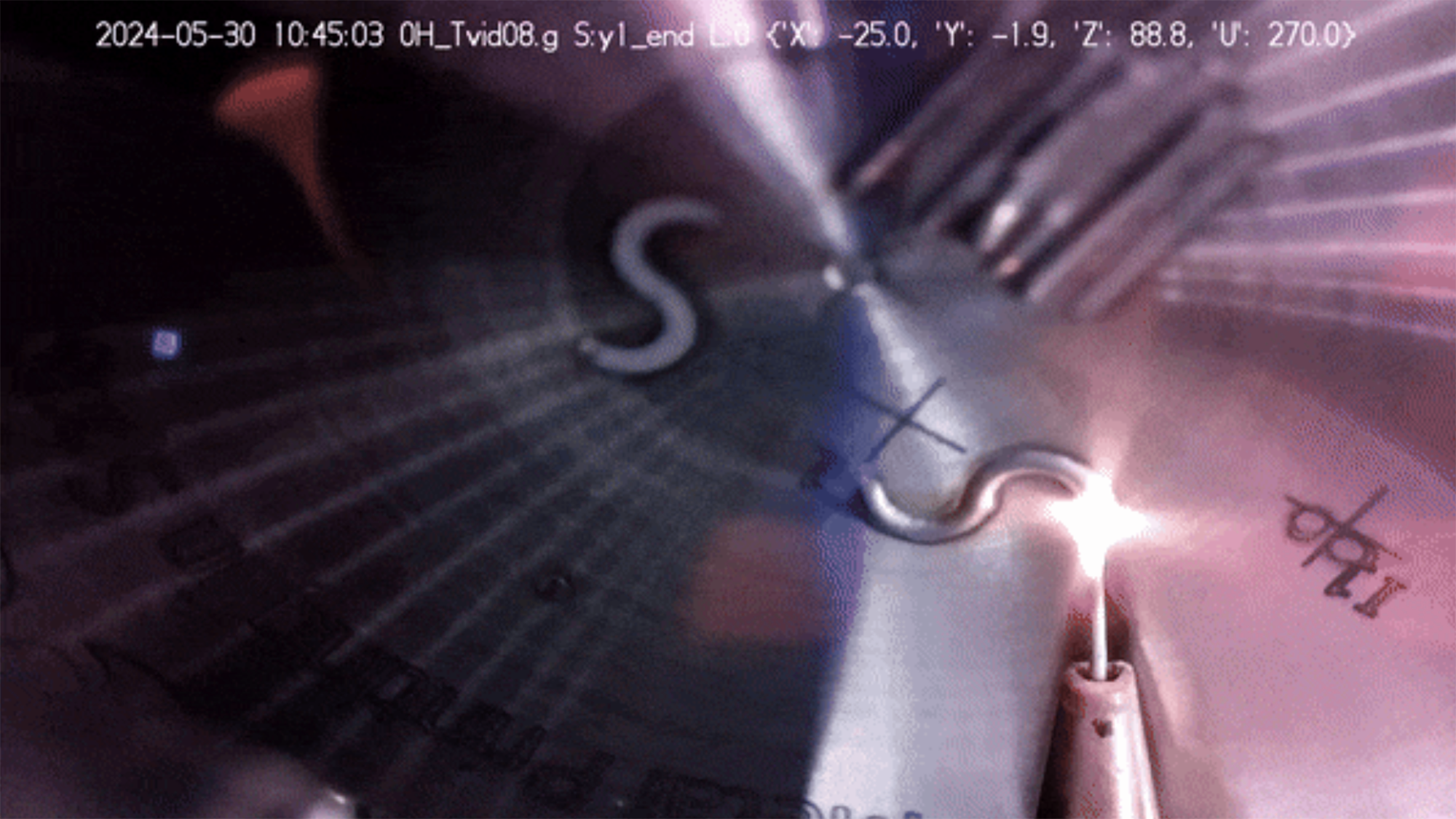

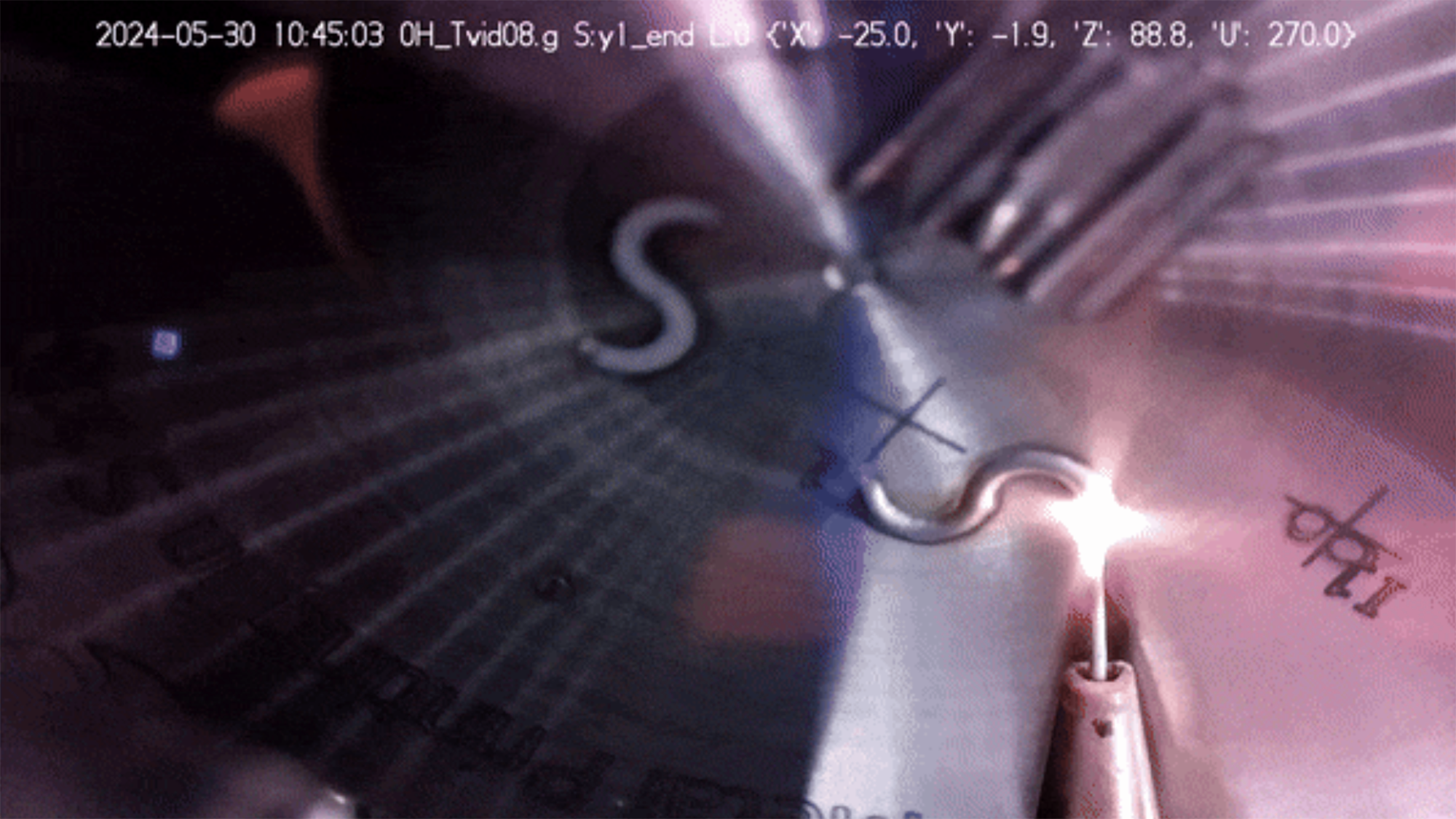

The first metal 3D printer aboard the International Space Station successfully dribbled out a molten “S curve” last Thursday, in what the European Space Agency (ESA) is calling a “giant leap forward for in-orbit manufacturing.”

Combining a high-power laser and stainless-steel wire, an Airbus-built metal 3D printer deposited its first liquefied test lines inside the ESA’s Columbus research module.

For “safety reasons,” the machine operated in a “fully sealed box, preventing excess heat or fumes from escaping,” the agency wrote, adding that the laser on the printer is “about a million times more powerful than a standard laser pointer.” Microgravity researchers at the French space agency CNES oversaw the project remotely from facilities in Toulouse, alongside Airbus and the ESA.

“The quality is as good as we could dream,” said Airbus’ lead system engineer for the project, Sébastien Girault, in a statement. ESA technical officer Rob Postema said the project’s success leaves the agency “ready to print full parts in the near future.”

The ESA plans to continue testing the printer. “Four shapes have been chosen for subsequent full-scale 3D printing, which will later be returned to Earth to be compared with reference prints made on the ground in normal gravity,” added the agency. Two of the resulting printed parts will go to the ESA’s main research center in Noordwijk, Netherlands, while remaining two will head to the European Astronaut Centre in Cologne, Germany and the Technical University of Denmark. The ESA and Boeing did not immediately respond to PopSci’s requests for more information on subsequent printing efforts.

In January, after the printer launched aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket as part of an ISS resupply mission, the ESA stated that the ability to build “more complex metallic structures in space” would be a “key asset for securing exploration of Moon and Mars.”

NASA expressed a similar sentiment on additive manufacturing in 2014, when its plastic 3D printer extruded a printhead faceplate, the first 3D-printed object in space. That printer went on to produce a ratchet wrench and a specimen container. The U.S. agency has argued that empowering astronauts to print spare parts and tools on demand will help address the logistical challenges inherent in deep space exploration, where resupply missions would be less feasible than those meant for the orbiting ISS.

Beyond enabling exploration, the ESA also alluded to 3D printing’s potential impact on space trash, as printing parts in space could reduce the need for resupply missions and might even enable astronauts to salvage some of the junk humans have left behind up there. “One of ESA’s goals for future development is to create a circular space economy and recycle materials in orbit to allow for a better use of resources, such as repurposing bits from old satellites into new tools or structures,” the agency stated.

Update June 5, 2024 1:09PM: Rob Postema, an engineer for the ESA’s LEO Exploration Group, told Popular Science that the next 3D test prints will include a cylindrical structure with thin walls as well as a portion of an unspecified tool. These designs were “printed on ground (before flight) to be able to compare results of printing on ground and in flight, and understand the differences the space environment may cause,” Postema said.