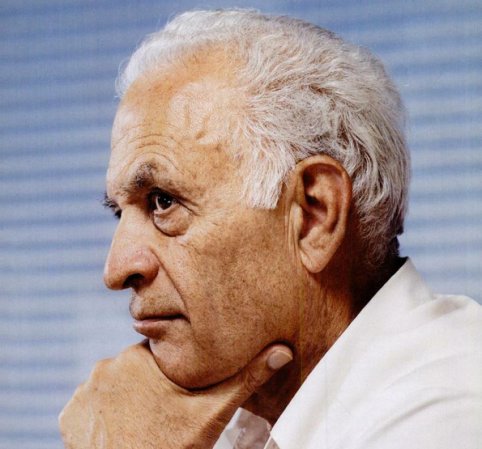

Back in the early days of the CIA, the agency was apparently a little strapped for creativity. Under the watchful eye of Allen Dulles, who headed up the spy center between 1953 and 1961, the CIA turned to British fiction for tech tips.

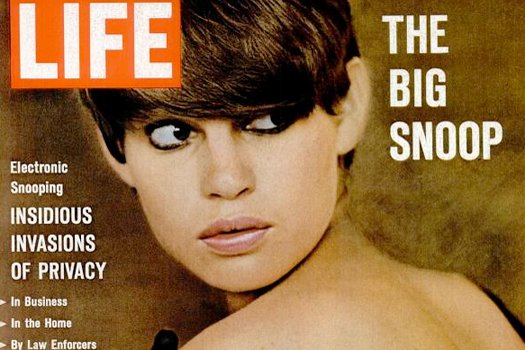

In this article Dulles penned himself for LIFE magazine’s April 1964 issue, he describes his close friendship with Ian Fleming, author of the James Bond novels and a former intelligence officer.

During a time when the CIA kept a tight lid on its pop culture image stateside, the Bond novels (with their favorable outlook on the American agency) “enjoyed something of a monopoly when it came to what people read about the CIA,” as University of Warwick professor Christopher Moran writes in his recent analysis of the author’s influence on the CIA. In addition to good press, the spooks also got a couple good gadget ideas from Fleming’s work.

It’s a bit hard to read, but amongst all the humblebragging about his bro-love with Fleming, Dulles drops in a little tidbit about spy gadgets. Namely, he really wanted the CIA to develop a real-life version of the homing-beacon Bond used to track his enemies’ cars in Goldfinger. The end result “had too many bugs in it,” he wrote, but the exercise wasn’t at total waste, “because sometimes you came up with other ideas that did work.”

One of the ideas Dulles stole straight from 007 was the poison-tipped knife shoes worn by the villain in From Russia With Love, a gadget Dulles admitted the CIA recreated in separate 1964 interview with LIFE. Whether CIA agents were more successful at wielding it than Rosa Klebb, we don’t know.

Perhaps this friendship even serves as an explanation for why the CIA’s attempts to assassinate Cuban leader Fidel Castro were so…Bond-worthy. Exploding cigars? A wetsuit contaminated with a fatal disease? It could be just coincidence, but it makes a pretty compelling conspiracy theory. The Russian Izvestia even wrote in 1962, “Obviously American propagandists must be in a bad way if they have recourse to the help of an English retired spy turned mediocre writer.”

Hey, you can’t blame them for knowing a good idea when they heard it!

Warwick’s paper is featured a recent issue of the Journal of Cold War Studies.