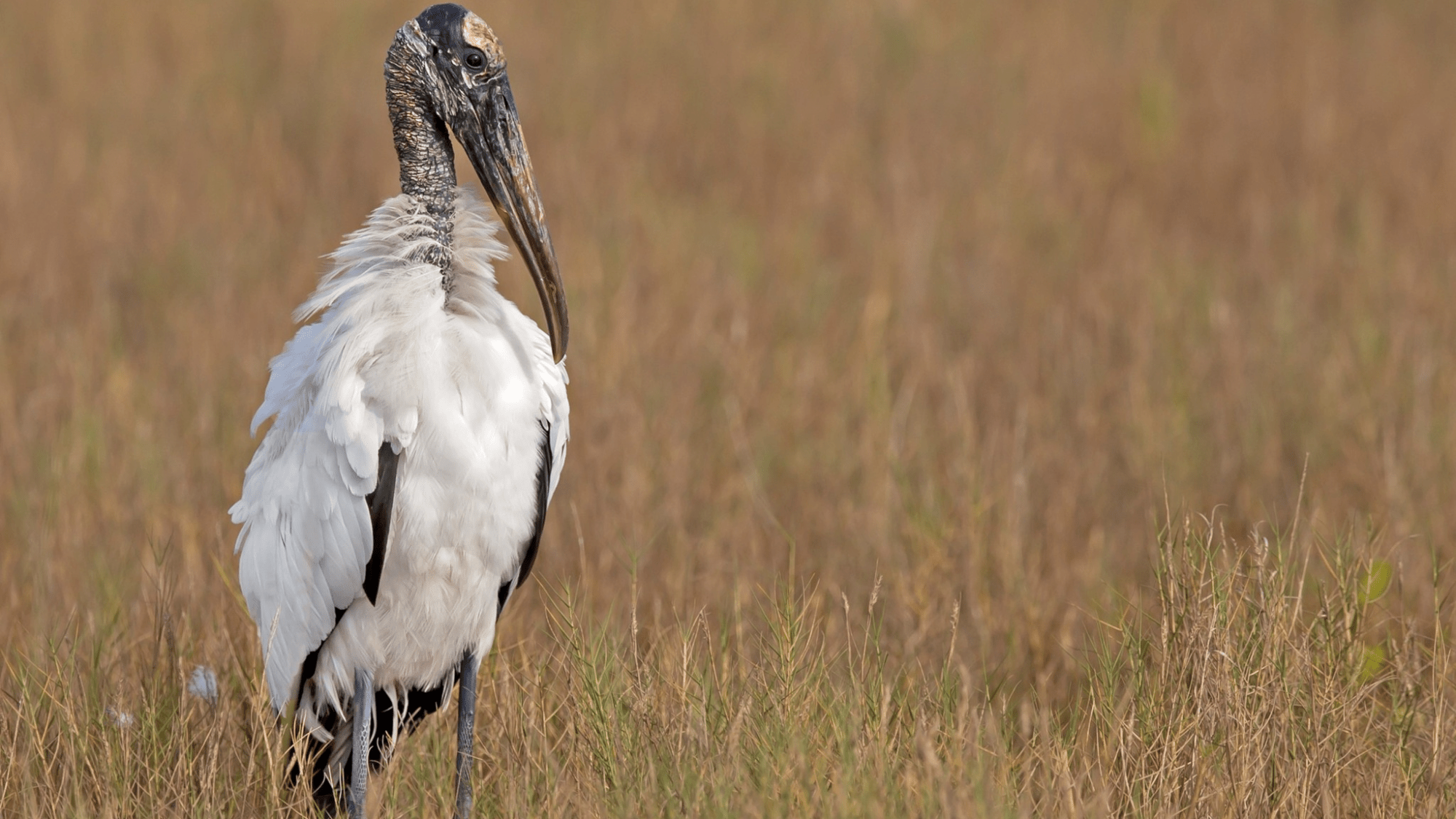

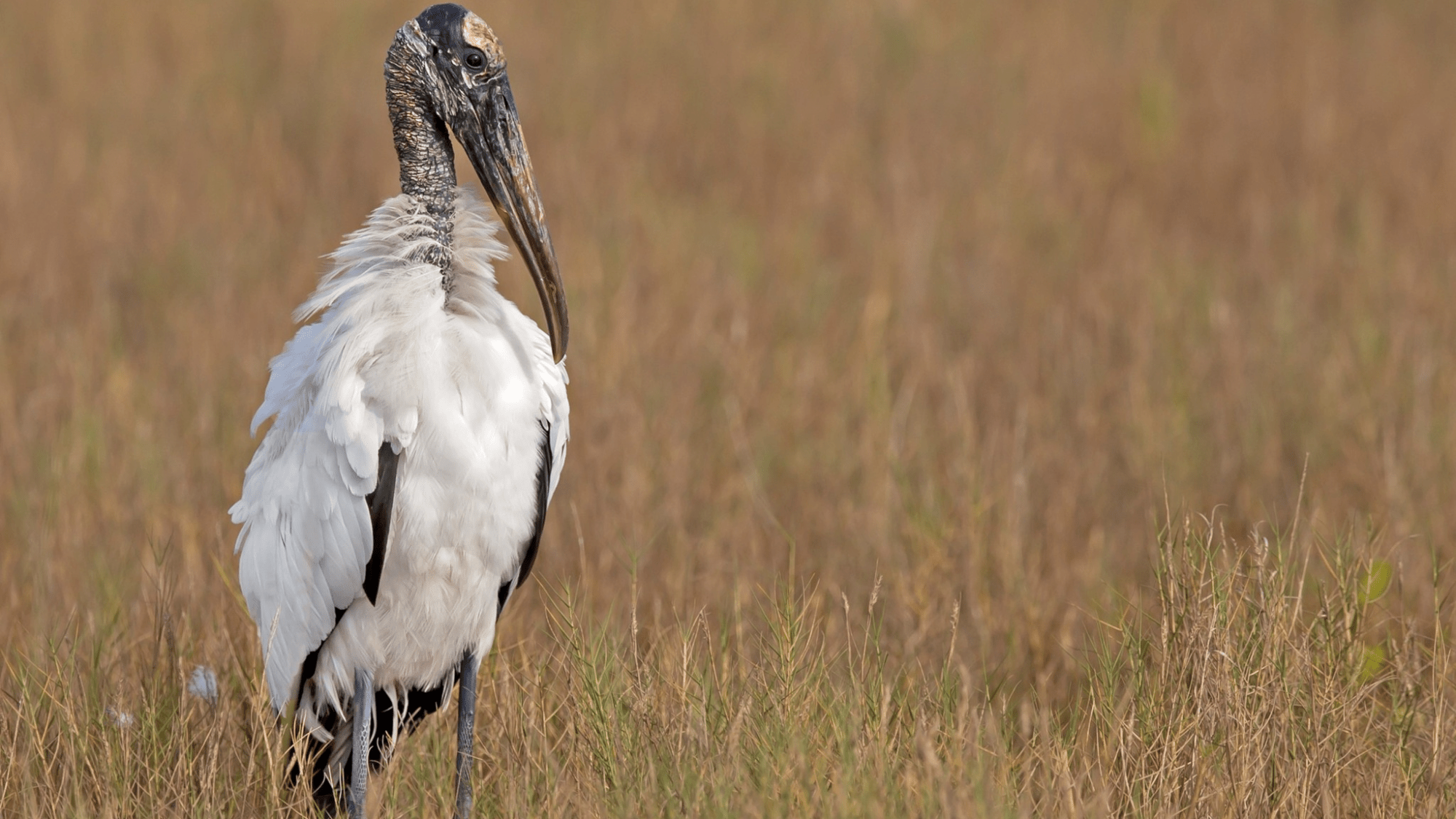

After over 40 years of recovery efforts, one population of the wood stork (Mycteria americana)is being removed from the federal list of endangered and threatened wildlife. The large birds are as tall as 45 inches with wingspans that can reach 65 inches and are the only native storks in the United States. They are primarily found in the southeastern United States, where they feed on fish.

Wood storks were listed as endangered in 1984, when its population had dropped by over 75 percent—from roughly 20,000 nesting pairs to about 5,000 nesting pairs—primarily due to wetland loss.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) has determined that the birds are no longer in immediate danger of extinction. The FWS estimates that the wood stork breeding population has 10,000 to 14,000 nesting pairs across roughly 100 colony sites. They are now found on the coastal plains of Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina.

Dedicated conservation efforts and the birds’ adaptability are some of the likely reasons behind this rebound. They have adapted to new nesting areas, including coastal salt marshes further north, flooded rice fields, floodplain forest wetlands, and even golf courses and retention ponds.

“Even when they’re in odd habitats, it’s still exhilarating to see these wild birds doing what they do in a natural marsh,” Dale Gawlik, endowed chair for conservation and biodiversity at Texas A&M University’s Harte Research Institute, told USA Today. “The birds have the flexibility to explore new habitats and eat new foods and that might be really important in a period when the environment is changing rapidly, like it is now.” Gawlik worked on wood stork recovery in Florida before moving to Texas.

However, not everyone is convinced that the birds should be taken off of the Endangered Species List. Environmental groups including Audubon Florida and the Center for Biological Diversity fear that their populations have not recovered enough. Advocates are concerned about what would happen if wood stork colonies are found on private lands when they are no longer federally protected. Wildlife officials in North Carolina supported removal, while the state of Georgia supported it with caveats, raising similar concerns about private land.

They also still face the uphill battle of future habitat loss in wetlands.

“This is a short-sighted and premature move. Wood storks need wetlands to survive, and that habitat is facing overwhelming pressure,” Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC) Wildlife Leader Ramona McGee wrote in a statement. “It is disappointing that Fish and Wildlife Service largely brushed away serious concerns about how losses to wetlands protections and climate change’s consequences for our coast increase threats to our U.S. population of wood stork. This delisting comes at a time when species face a storm of proposed federal rollbacks to habitat protections that are likely to imperil wood storks and countless other Southeastern species.”

The FWS says it has a 10-year post-delisting monitoring plan to make sure that the species’ recovery is maintained. The official delisting of the wood stork will finalize on March 9, 2026.