The high-adrenaline winter sport of skijoring, derived from the Norwegian word for “ski driving,” takes so many forms that it even defies uniform pronunciation.

“If you go to France, it’s skijoering, pronounced SKEE-zhor-ing. In German, it’s skijöring, pronounced SHEE-yuh-ring,” says Loren Zhimanskova, founder of Skijor International and Skijor USA. “In Norway, it’s skikjøring, pronounced SHEE-shuh-ring. Every culture has its own version, and that’s part of what makes the sport so special.”

This changeability goes beyond umlauts and accents—it’s at the heart of the evolution and modern practice of this eclectic sport.

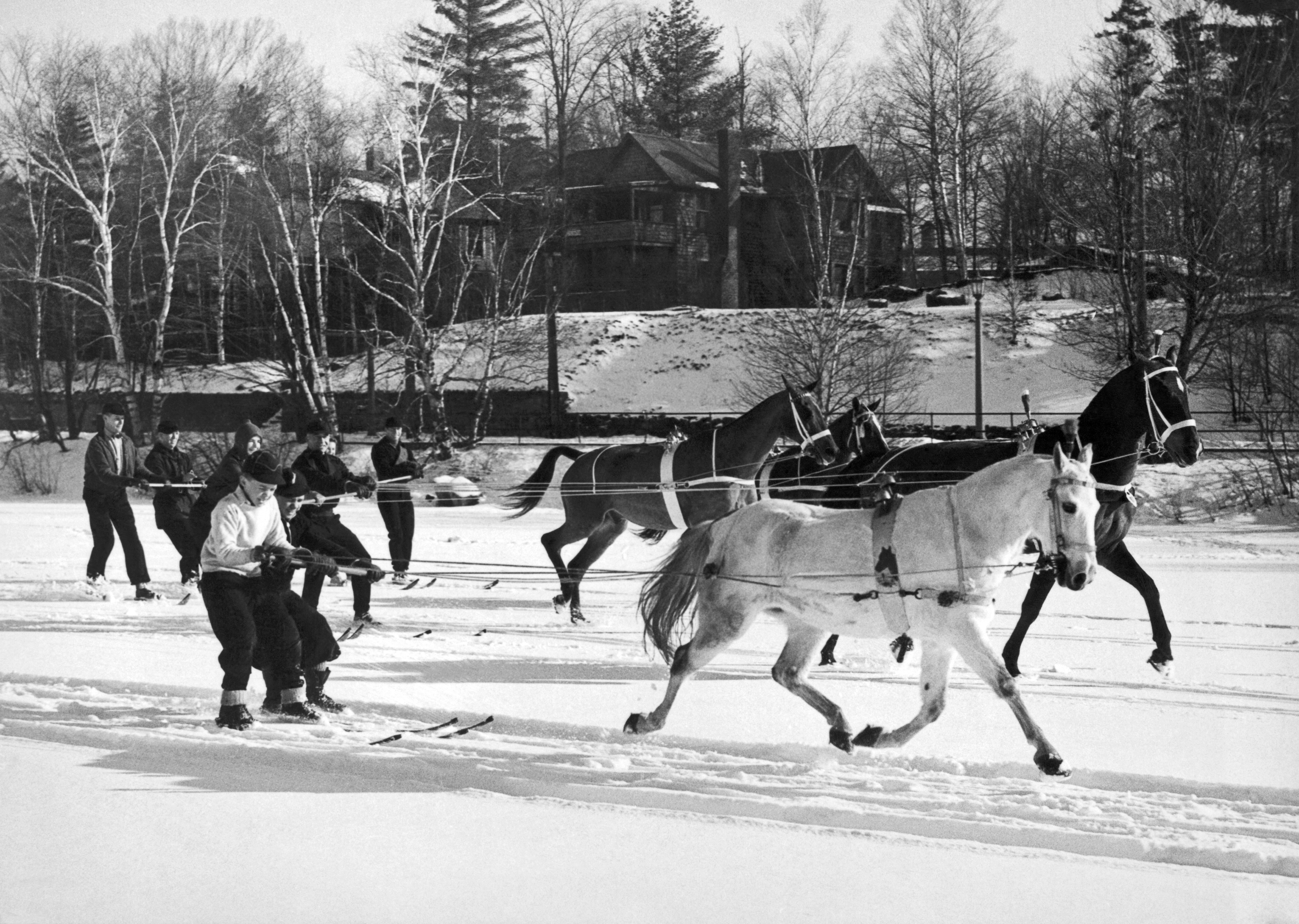

At its core, skijoring is a winter sport in which a skier is pulled across the snow by a horse. In European competitions, the horse typically runs riderless, while in Western-stye competitions a mounted rider steers the horse through a fast-paced obstacle course.

“It’s that free-flowing, wildhearted diversity that makes our sport so attractive,” Zhimanskova says. But that diversity is also why skijoring may never again grace the Olympic stage after being included as a demonstration event in the 1920s.

What is skijoring?

The two main ways to skijor don’t have much in common. In Europe, a lone skier navigates a riderless horse around an oval track, racing shoulder-to-shoulder with other competitors. In the American West, a rider guides the horse through an obstacle course while the skier navigates gates, lands jumps, and sometimes catches rings, all while managing roughly 33 feet of rope at speeds that can reach 40 mph.

What does it feel like to travel on horse-drawn skis? Zhimanskova says the sensation is similar to waterskiing: sitting back slightly against the pull of the rope, keeping the knees flexed, and relying on arm and leg strength to stay upright.

“It might be a bit easier than water skiing, because with waterskiing, you have to go fast to stay afloat,” she says. “With a horse, you can go slower.”

Related Stories

Zhimanskova notes that skijoring has a very different sensation than horseback riding on snow. With the skier’s weight distributed across skis rather than concentrated in a saddle, the horse can move more efficiently over snowy terrain, while the rider and skier are able to navigate sharper turns without destabilizing the horse.

From winter work to winter sport

Long before skijoring became a competitive sport, it was a practical form of winter transportation. The Sami people of Scandinavia used skis and reindeer to efficiently traverse snowy expanses, and Nordic militaries later adapted the practice to move troops and supplies through harsh winter conditions.

Over time, people began to appreciate a different aspect of this snowy time-saver—it was fun. By the early 1900s, skijoring had evolved into a recreational activity in the Alps, where it developed into an organized sporting activity. It eventually attracted some high-profile fans, including Baron Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the Winter Olympics. His enthusiasm for the sport led to its inclusion as a demonstration event at the 1924 Games in Chamonix, France, and again in the 1928 Games in St. Moritz, Switzerland.

As the sport eventually made its way west, it evolved a distinctly American style. By around 1914, American tourists began bringing skijoring back from their European vacations, and it began appearing at resorts like Mirror Lake in Lake Placid, New York. These early U.S. iterations hewed closely to the European roots of the sport.

“The Western version started in towns like Jackson, Steamboat, and Banff, and was more free-spirited and rugged, more about testing your skills,” says Zhimanskova. “That’s how rodeo started. Cowboys roped as part of their jobs, but when they had time off they said, ‘Well, who can rope the best?’ It became a friendly competition, and then evolved into a structured sport, like rodeo.”

Skijoring continues to take many forms

In modern practice, skijoring has splintered into a wide range of styles—not even the horse is set in stone. Some skijorers are pulled by dogs or miniature ponies, others by snowmobiles, motorcycles, or cars, and at least one donkey has reportedly gotten in on the action. Still, the most common form of the sport involves a skier pulled by a galloping horse, either with a rider or without.

It’s uncertain whether skijoring will reappear in future Winter Olympics. Zhimanskova believes gaining approval from the International Olympic Committee would require a level of international standardization that might be at odds with the sport’s notoriously untamed nature.

Still, some efforts have been made to add structure to the sport without sacrificing its freewheeling spirit. Zhiimanskova helped establish the SkijorCup, a standardized point system designed to connect competitions across events while preserving the sport’s culture and emphasis on equine safety.

“Skijoring races have always resisted a governing body because people involved in the sport are so inherently independent,” she says. “But that doesn’t mean they aren’t willing to work together to grow and improve. The trick is finding the right formula that unifies, allows for independence, and doesn’t involve governing or sanctioning.”

Beyond the competition itself, modern skijoring has developed a distinct visual culture that’s part of what makes it so magnetic. Modern skijoring events in the American West often look like a mashup of apres-ski attire and Yellowstone-esque Western flair.

Fur coats, chaps, and cowboy hats add a renegade swagger to pristine snowscapes, and participants and spectators alike embrace the sport’s anything-goes aesthetic. Some competitions even celebrate skijor chic through organized “red carpet” events.

“I always say it’s the Kentucky Derby, but on snow with a twist,” says Kylee Nielson, a competitive skijor rider who, together with skier Magnolia Neu, took home the first-ever Women’s Division championship buckle at PRO Skijor’s recent Frontier Tour in Heber City, Utah.

“Tons of fur coats, cowboy hats, chaps—the crazier, the better.”

“Three heartbeats”

Beneath the chaps-clad pageantry, skijoring relies on an intimate partnership of timing and trust, leaving little room for error. Megan Smith, a novice skijorer married to seasoned competitor Patrick Smith, has come to understand that firsthand.

“It’s a sport of three athletes, not just the rider and the skier,” says Megan, a former restaurateur and photographer who connected with Patrick after posting her photos of his races. “Skijor is rider, skier, and horse.”

“They call it ‘three heartbeats,’” adds Patrick.

The phrase exemplifies how closely the sport binds this essential trio, who share very real consequences if one “heartbeat” should fall out of sync.

This three-athlete interdependency was truly driven home recently for Patrick. During a two-day event, he was riding near the top of a stacked field when a turn went wrong. The horse, Lady Porcha, lost her footing on the icy course and went down, sending both of them sliding briefly across the track.

Lady Porcha quickly got to her feet and finished the run uninjured, but Patrick was knocked to the ground as the skier’s rope caught his spur and pulled his boot free.

“You skipped like a stone on a pond,” Megan recalls.

The fall drew a collective gasp from the crowd, and people rushed in to help. Patrick walked away with a twisted ankle, shaken but intact—and relieved, above all, that the horse was okay.

Patrick and Megan participate in skijoring competitions throughout the winter. While Patrick approaches the sport as a serious contender, Megan—who picked up a win of her own recently—is more drawn to the fun of it all.

“He’s like ‘I’m here to win,’ and I’m there to see my friends,” says Megan. “We’ve found a really good community here. Everyone is positive and roots for each other.”