This article was originally featured on Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

During Japan’s sweltering summers, nothing hits the spot quite like a frozen orange. The popular treat, known as reito mikan, tastes great when made at home. But it tastes even better when made 850 meters below the ocean’s surface. “A bit salty, but super delicious,” says Shinsuke Kawagucci, a deep-sea geochemist at the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology.

The frozen fruit was the product of a particularly tasty scientific experiment. In 2020, Kawagucci and his colleagues designed a highly unusual freezer—one built to operate in the intense pressure of the deep sea. The frozen orange, chilled in the depths of Japan’s Sagami Bay, was their proof that such a thing is even possible.

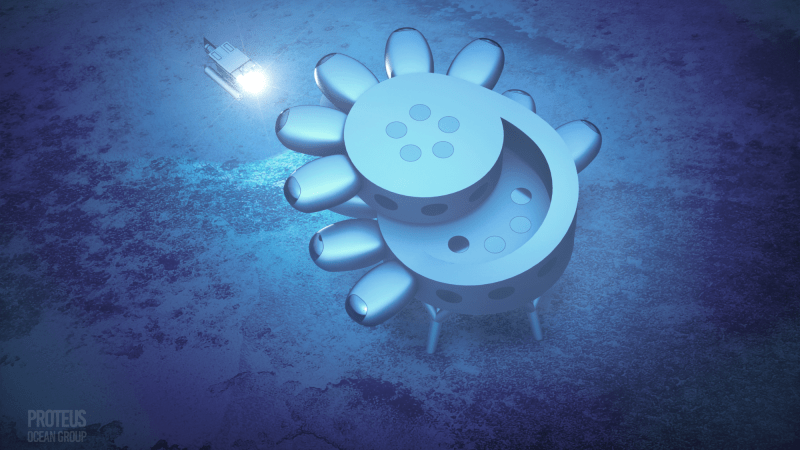

Kawagucci and his colleagues’ prototype deep-sea freezer is essentially a pressure-resistant tube with a thermoelectric cooling device inside. By running an electric current through a pair of semiconductors, the device creates a temperature difference thanks to a phenomenon known as the Peltier effect. The device can chill its contents down to -13 °C—well below the freezing point of seawater. Because it does not require liquid nitrogen or refrigerants to cool its housing, the freezer can be built both compactly and with minimal engineering skill.

With a few adjustments, Kawagucci and his colleagues write in a recent paper, their prototype freezer can be more than a fancy snack machine. By offering a way to freeze samples at depth, such a device could improve scientists’ ability to study deep-sea life.

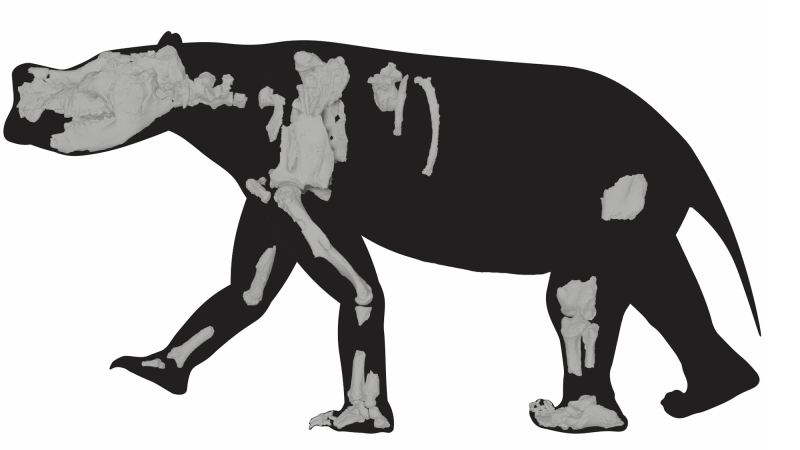

Bringing animals up from the deep is often a destructive affair that can leave them damaged and disfigured. The best example is the smooth-head blobfish, a sad, misshapen lump of a fish that got its name from the blob-like shape it takes when wrenched from its home more than 1,000 meters below. (In its deep-sea habitat, the fish looks like many other fish and hardly lives up to its name.)

Although scientists have previously designed tools to keep deep-sea specimens cold on their way to the surface, the new prototype freezer is the first device capable of freezing specimens in the deep sea. Similarly, other tools do exist that allow scientists to collect creatures from the deep unharmed, such as pressurized collection chambers. Yet these often don’t work well for small and soft-bodied deep-sea animals that are prone to dying and decomposing when kept in such containers for too long—an oft-unavoidable reality, says Luiz Rocha, the curator of ichthyology at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. “It can take hours to bring samples up,” Rocha says.

A device that freezes samples first would stave off degradation, enabling better scientific analysis of everything from anatomy to gene expression. While the freezing process will undoubtedly damage the tissues of some of the deep’s more delicate life forms, specimens damaged by freezing tend to be more useful to scientists than specimens damaged by decomposition—at least when it comes to DNA analysis.

The prototype freezer takes over an hour to freeze a sample, which is probably “too slow to be broadly useful,” says Steve Haddock, a marine biologist with the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute in California who studies bioluminescence in jellyfish and ctenophores. Every minute of deep-sea exploration is precious, he says. “We typically spend our time searching for animals, and we bring them to the surface in great shape using insulated chambers.” However, if the freezing time could be improved, Haddock believes such a device could be “empowering” for those who study deep-sea creatures that are extremely sensitive to changes in pressure and temperature, such as microbes living on hydrothermal vents.

Kawagucci says he and his team plan to improve their freezer before testing it out on any living specimens. But he hopes that with such improvements, their tool will give scientists a way to collect even the most delicate deep-sea organisms.

In the meantime, Kawagucci is just happy his device proved that deep-sea freezing by a thermoelectric cooler is possible. “Throughout the Earth’s history, ice has never existed in the deep sea,” he says. “I wanted to be the first person to generate and see the ice in the deep sea with my freezer.” And when he finally sank his teeth into that tangy, salty, sweet reito mikan, “one of my dreams came true.”

This article first appeared in Hakai Magazine and is republished here with permission.