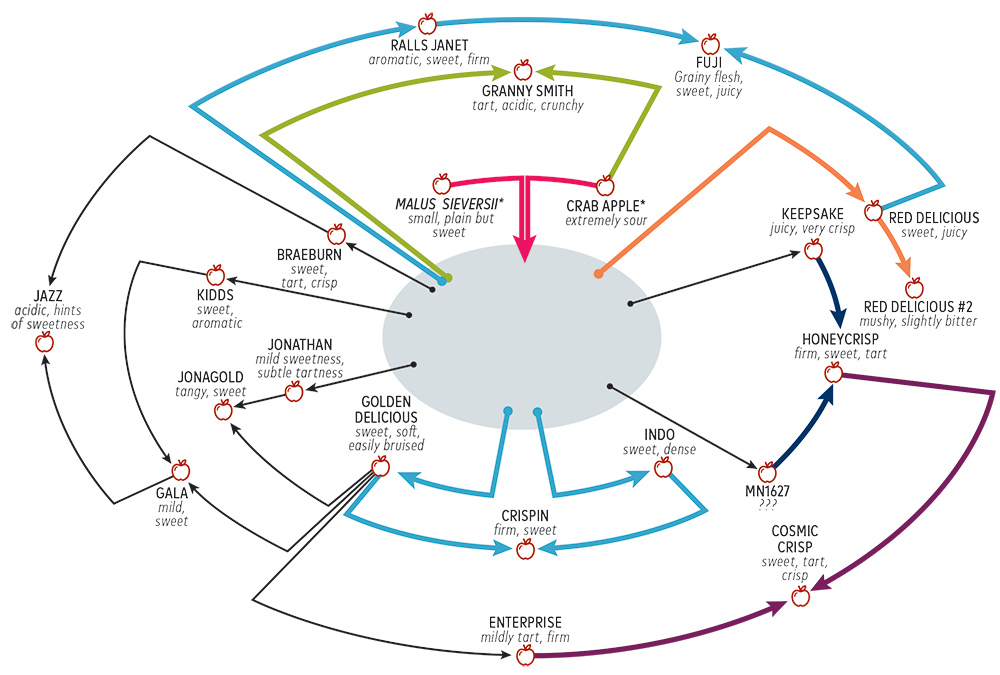

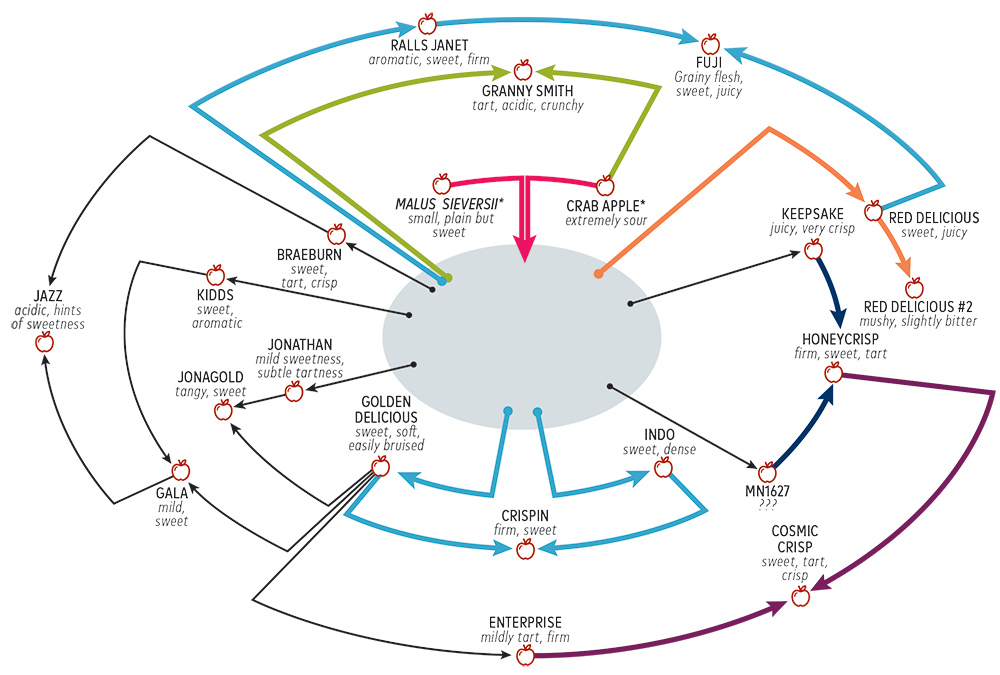

Planting apples is a game of chance in which every seed is a wild card. The pome’s genetics are so diverse that kernels from the same core sprout into entirely different varieties.

Malus Domestica

If Silk Road travelers had minded their litter, we wouldn’t have today’s apples. Kazakh fruits hitched rides to China and Europe, where trees grown from discarded cores cross-pollinated with soft Asian and sour crab varieties. Farmers cultivated some of the European offspring, creating a new species—the ancestor to all modern pomes.

Red Delicious

A random seedling in an 1870s Iowa orchard blossomed into crisp red globes. Half a century later, serendipitous genetic mutations led to a deeper crimson skin. Apple breeders started to select excessively for the skin’s color and shelf-life-lengthening thickness, both of which sold more produce—but made for mealy fruit.

Granny Smith

According to lore, there really was a Granny Smith. In the 19th century, the Australian farmer tossed some French crab apples by a creek outside her house, and one of them sprouted into a tree with vivid, green fruit. Genetic analysis shows some M. domestica in there too, so Granny might not have had a true crab after all. But it’s a nice story.

Crispin (née Mutsu)

While the U.S. devoured the Red Delicious, researchers across the Pacific crossbred classic American varieties to produce sweeter, juicier, and hardier fruits. The Indo and Golden Delicious together became the Crispin (or the Mutsu in Japan). The Fuji variety, a derivative of Thomas Jefferson’s own Ralls Janet, is an import too.

Honeycrisp

Developed and patented at the University of Minnesota, the sugary, moist Honeycrisp debuted in the ’90s, just as Red Delicious sales were slowing. Horticulturalists bred one of their own varieties, MN1627 (never released to the public), and selected for cells that were twice as large—giving the flesh a characteristic crunch.

Cosmic Crisp

Consumers will get their first taste of this much-hyped apple in 2019, two years after the largest launch in the industry’s history: 11.6 million trees in Washington state. The pome gets its name from the yellow, starlike speckles on its reddish skin. Breeders spent more than a decade crossing to create its sweet-and-tart flavor and robust constitution.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2018 Life/Death issue of Popular Science.