What Are Gravitational Waves And Why Do They Matter?

If we detect them, it could mean a lot about the universe

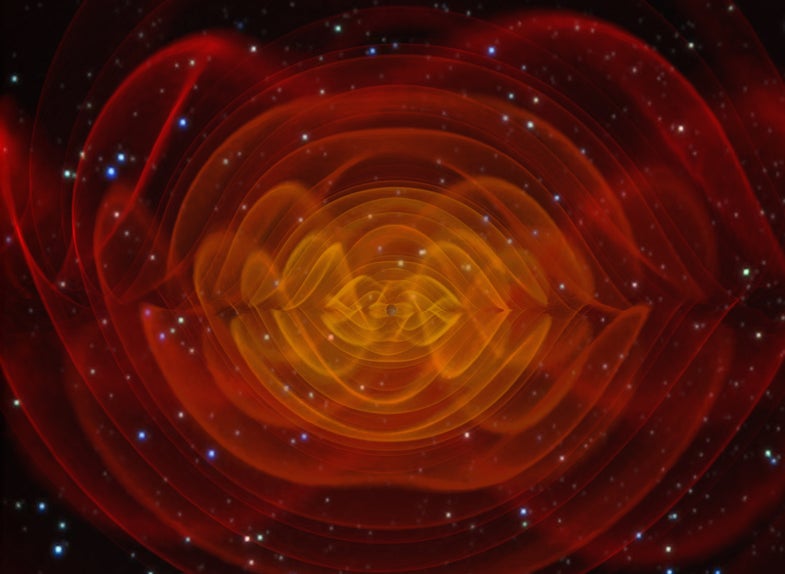

Simulation of Gravitational Waves

Physicists have been buzzing (or rather, tweeting) about the possibility that the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) experiment finally discovered gravitational waves. LIGO has been searching for these cosmic ripples for over a decade. Last September, it upgraded to Advanced-LIGO, a more sensitive system that’s also better at filtering out noise. Advanced-LIGO has a much stronger chance of collecting concrete evidence of gravitational waves—if it hasn’t already.

Scientists may be excited, but talk of gravitational waves leaves most people scratching their heads. What are these cosmic vibrations, and why are they making waves in the scientific community?

What are gravitational waves?

Gravitational waves are disturbances in the fabric of spacetime. If you drag your hand through a still pool of water, you’ll notice that waves follow in its path, and spread outward through the pool. According to Albert Einstein, the same thing happens when heavy objects move through spacetime.

But how can space ripple? According to Einstein’s general theory of relativity, spacetime isn’t a void, but rather a four-dimensional “fabric,” which can be pushed or pulled as objects move through it. These distortions are the real cause of gravitational attraction. One famous way of visualizing this is to take a taut rubber sheet and place a heavy object on it. That object will cause the sheet to sag around it. If you place a smaller object near the first one, it will fall toward the larger object. A star exerts a pull on planets and other celestial bodies in the same manner. You can see this experiment in action in the video below.

While the rubber sheet analogy is not an exact representation of how spacetime works, it demonstrates that what we think of as a void can be visualized as a dynamic substance. Any accelerating body should create ripples in this substance. But small ripples would fade out relatively quickly. Only incredibly massive objects—such as neutron stars or black holes—will create gravitational waves that continue to spread all the way to Earth.

How can we detect them?

A few different experiments are currently underway to search for these waves. The latest rumors are coming from LIGO, which looks for gravitational waves by tracking how they affect spacetime: As a wave passes by, it stretches space in one direction and shrinks it in a perpendicular direction.

LIGO aims to detect these changes using an instrument called an interferometer. This device splits a single laser beam into two and sends both beams shooting off perpendicularly to each other. If the beams travel equal distances, bounce off mirrors, and come back, the waves that make them up should still be in alignment when they return. But a passing gravitational wave can actually change the distance of each arm, which would change the distance that each beam travels relative to its sibling. When the beams return to their source, scientists would be able to detect this change. However, gravitational waves change the length of the interferometer’s arms by an incredibly tiny amount: roughly 1/10,000th the width of an atom’s nucleus. To pick up such a tiny change, LIGO must filter out all other sources of noise, including earthquakes and nearby traffic. Although LIGO found no gravitational waves in nearly a decade of operation, its recent upgrade to Advanced-LIGO should give it a better chance.

Advanced-LIGO will have to compete with the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Laser Interferometer Space Antenna, or LISA. LISA, which will act like a giant LIGO in space, is getting a dry run this year—the ESA launched the LISA Pathfinder in December. It will stay in space for a few months to test the technology that will eventually be deployed in future LISA missions.

But lasers aren’t the only way to detect changes in spacetime. For example, the North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves, or NANOGrav, looks for gravitational waves by looking at the bursts of radio waves emitted by the neutron stars called pulsars. These radio wave pulses are normally strictly timed, so if they arrive early or late, it could be because a gravitational wave interfered with their journey to Earth.

The BICEP2 Telescope At Twilight

Other experiments look for a specific type of gravitational waves created in the aftermath of the Big Bang. They do so by observing the radiation left over from the Big Bang. If the Big Bang made gravitational waves, scientists would expect to see swirls in this radiation’s polarization. Programs like Background Imaging of Cosmic Extragalactic Polarization (BICEP), Harvard’s series of experiments at the south pole, observe the leftover radiation in an attempt to find the telltale polarization patterns.

What’s the point of finding gravitational waves?

You Ask, We’ll Answer

Well, gravitational waves give us another way to observe space. For example, waves from the Big Bang would tell us a little more about how the universe formed. Waves also form when black holes collide, supernovae explode, and massive neutron stars wobble. So detecting these waves would give us a new new insight into the cosmic events that produced them.

Finally, gravitational waves could also help physicists understand the fundamental laws of the universe. They are, in fact, a crucial part of Einstein’s general theory of relativity. Finding them would prove that theory—and could also help us figure out where it goes astray. Which could lead to a more accurate, more all-encompassing model, and perhaps point the way toward a theory of everything.