Your stomach is extremely moody—at any given time, a complex interplay of factors such as hormone production and various neurological signals can leave you feeling hungry, overstuffed, excited, or nauseous. These experiences stem directly from the enteric nervous system (ENS), which controls gastrointestinal tract functions along a path known as the gut-brain axis. The ENS is so complex, in fact, that it is often referred to as your “second brain.”

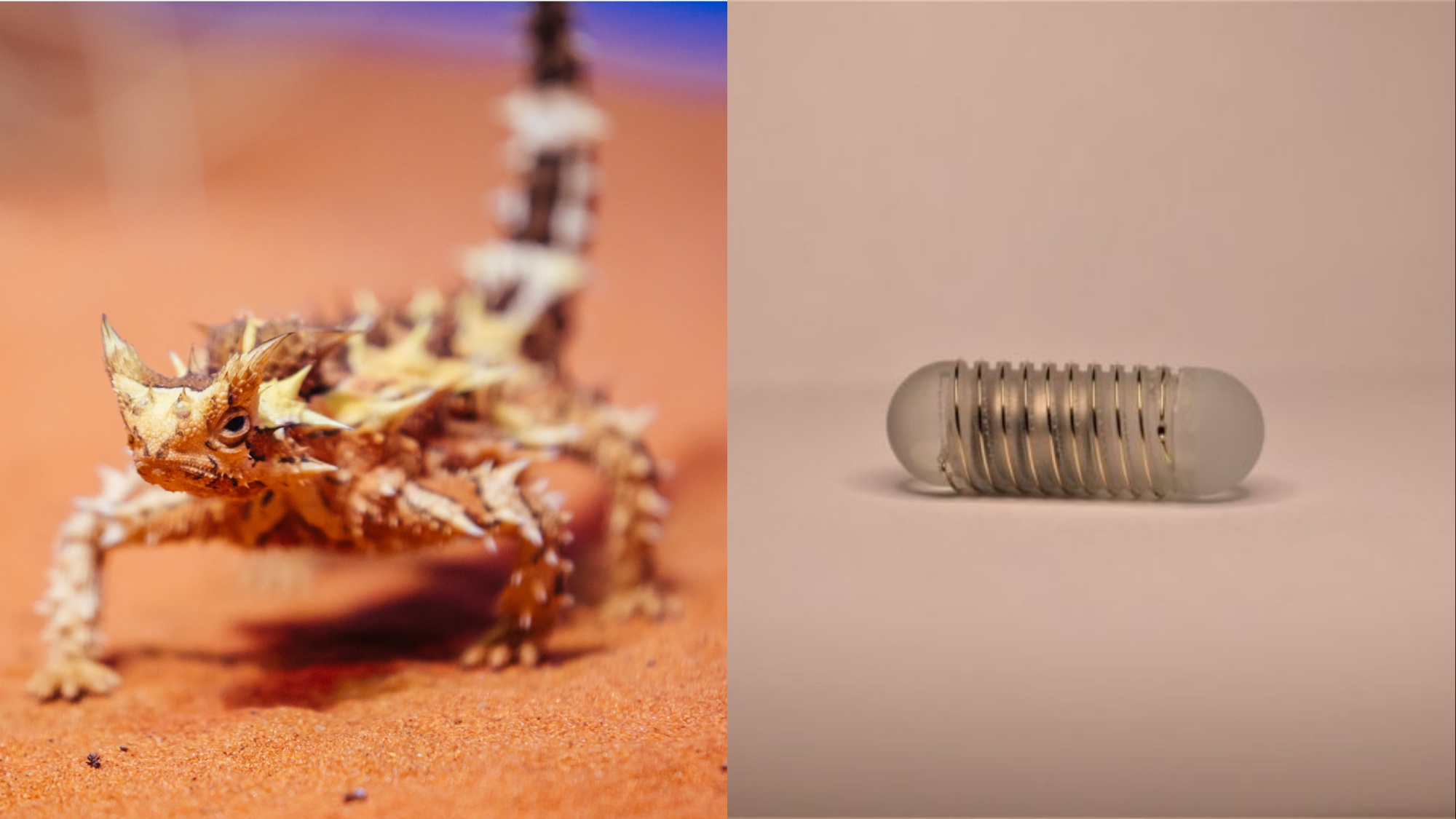

Because of this, there are a number of ways for things to go sideways, resulting in issues such as suppressed appetites and slow digestion. Recently, however, researchers developed a first-of-its-kind treatment to help spur hunger via stimulating hormone levels in the gut—an “electroceutical” ingestible capsule inspired by a “water wicking” reptile.

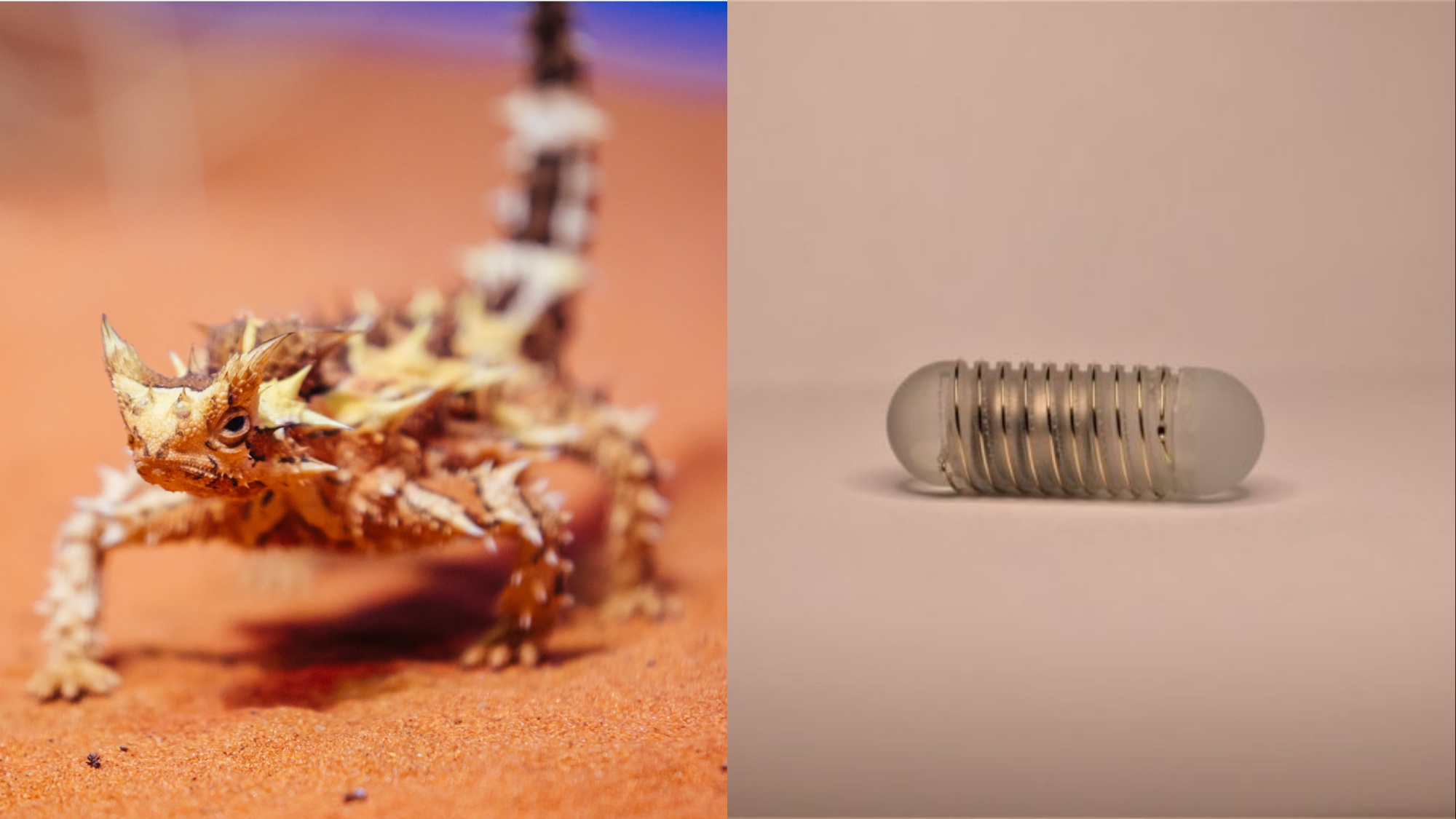

In a new paper published by a team of scientists at NYU Abu Dhabi working alongside experts at MIT, the team explored a novel way to “significantly and repeatedly” induce the production of ghrelin, a hormone that triggers hunger. To accomplish this, they looked to the Australian thorny devil lizard, whose spiky skin is evolved to transport any water it touches towards the reptile’s mouth. Similarly, the research team’s ingestible device features a grooved, hydrophilic exterior designed to defer fluids away from the stomach’s inner lining. When this occurs, the pill-shaped tool’s electrodes come into direct contact with the tissue to produce a tiny current stimulating ghrelin production.

[Related: Doctors need to change the way they treat obesity.]

Dan Azagury, an associate professor and Chief of Minimally Invasive and Bariatric Surgery at Stanford University who was not involved in the study, admired the new device, and said they found the findings “really intriguing.”

“I love the creativity of the device, the idea, and how they found a way to get around the fluid constraints,” Azagury said via email, but cautioned that “even if that works, the path for this to show clinical efficacy in a disease as complex as obesity, is very, very challenging.”

Azagury points towards experts’ still relatively poor understanding of gut hormones and the gut-brain axis, which are “more complex than we think, and likely underutilized.” As an example, he offered that the “new blockbuster drugs” used to treat obesity are based on gut hormones only discovered in the 1980s, far after doctors had begun performing weight loss surgeries.

Although Azagury estimates there is a “long road ahead” before the device is commercially used to treat diseases, its creators are more optimistic. “It’s a relatively simple device,” Giovanni Traverso, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at MIT and gastroenterologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and the senior author of the study, argued in a statement for MIT. “So we believe it’s something that we can get into humans on a relatively quick time scale.”