Going by our archives, the only thing more hyped-up than flying cars and humanoid robot assistants were cool futuristic homes — homes that could converge their walls to create new rooms, that could adapt to any environment, and that could play with your children while you took an afternoon nap. In terms of functionality, houses of today haven’t changed much over the past fifty years. We still use good old brick, marble and cement as building materials. We still turn the microwave and TV on by our ourselves. For the most part, we still do our own chores. So what happened?

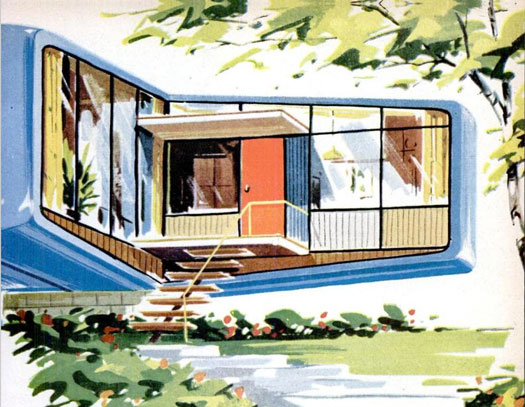

In some cases, we dreamed too big, perhaps spiraling into ideas that were decades ahead of their time. In the early 1980s, a band of designers at the Illinois Institute of Technology predicted that by the mid-1990s, we’d be using computers to build fully computerized, shippable, energy-efficient modular housing units. Microprocessors would control the appliances and adjust the ambiance, while robots would hang the laundry. Humans, meanwhile, would lounge around the indoor spas (alas, still not a standard feature) in between watching programs on holographic television sets.

The future that never was makes our Roombas and plasma TVs sound a little quaint, doesn’t it? We’re happy to report, though, that we have plenty of reasons to feel content with our non-computerized houses. In April 1956, a group of researchers at MIT tested plastic houses, the draw being that plastic walls would be easy to hose down on cleaning days. A couple of decades later, Goodyear began testing air-bubble houses, which would situate your family within an unnervingly spacious translucent dome. These days, neither sound particularly appealing, given their vulnerability to natural disasters and local hooligans.

Dismally enough, we predicted in 1982 that in order to conserve natural resources, people living in the year 2000 would be forced to use low-flush toilets and “miserly” shower heads. As much as we love robots and computer-controlled appliances here at PopSci, we’ll profess to choosing hot showers over talking microwaves any day of the week.