If not for the plaster cast on her leg, Paulette Sutton would be rolling in blood. Instead, she slouches in a doorway, watching her partner ram his bloody shoulder against a wall, drop to his hands and knees, and crawl across a grimy carpet, leaving behind a trail of red-smudged handprints.

“I’m not used to letting him have all the fun,” she grouses.

Over the past six months, Sutton, one of the country’s most respected bloodstain-pattern analysts, has taken her show on the road — blood-spattering her way across the United States. The National Institutes of Justice and the University of Tennessee’s Law Enforcement Innovation Center sponsor

Sutton’s mission: to educate, often

re-educate, homicide detectives and crime-scene investigators about the meaning and value of bloodstain evidence. For, according to Sutton, hers is a forensic specialty as drenched in myth and misconception as it is in gore.

A 27-year veteran of the Shelby County Medical Examiner’s office in Memphis, Sutton is the widely published protge of Herb MacDonell, the acknowledged father of bloodstain-pattern analysis in North America. “She’s almost as good as I think I am,” says MacDonell. When pressed for a serious assessment, MacDonell ranks Sutton as among the two or three best.

Without leg cast, Sutton stands a sturdy 5 feet 5, with a short thatch of salt-and-pepper hair framing a tanned face etched with laugh lines. On this day a torn foot ligament has forced her to take an unaccustomed backseat to her own protg, Steve Nichols. When not accompanying Sutton on road trips, Nichols works primarily as a forensic toxicologist. Today he is doing his best Jackson Pollock across the hospital-green walls of a derelict schoolhouse outside Lexington, South Carolina. (Sutton and Nichols use horse blood drawn during veterinary procedures and then thinned, with a splash of water, to mimic the consistency of human blood.)

“Give them a little arterial gushing,” directs Sutton, referring to the wave-like patterns produced by a severed artery under the pressure of a still-beating heart. “They always like a little arterial.”

The master, having decided to add some finishing touches to Nichols’ tableau, dons white coveralls and purple surgical gloves and hobbles across the room. She opens a plastic tackle box and, passing over compartments of bullet casings, matted hair and one-shot liquor bottles, selects some broken acrylic fingernails, playing cards and fake dollar bills. She smears them with blood poured from a bottle and flicks them across a table and onto the floor.

“We usually include at least one card game gone bad,” she says of the half-dozen mock homicides laid out in the school’s disheveled classrooms. Tomorrow, six police teams will work the scenes, applying Sutton’s teachings to develop theories as to weapons used, number of assailants, angles of attack, and possible progression of events.

Sutton’s most experienced students often present the greatest challenge,

she says, for many longtime law enforcement officials have some fairly predictable if inaccurate preconceptions. Sutton describes a recent death investigation involving a known drunkard found dead in a vacant house. Photographs show the dead man’s face to be a bloody pulp. “The lieutenant told me he had proof positive that it was an accident because there was no sign of cast-off,” says Sutton, referring to the bloodstain pattern created when blood slings off a weapon, another object or the human body in motion. “I don’t care if you swing a bloody cat by the tail, you won’t always see cast-off,” says Sutton.

Sutton’s more thorough search of the same death scene turned up a bloodied table leg and bedpost. The impact angle of the blood spatter on the bedpost aligned with the victim’s face in a way that suggested the post had been used as a weapon before being dropped to the floor, where it caught flying blood from a subsequent beating with the table leg.

Even more dangerous than oversimplification, says Sutton, are the many instances when blood-spatter experts go too far, claiming they can describe exactly how a murder

unfolded — with moment-by-moment, freeze-frame accuracy. Sutton scoffs at criminalists who claim spatter can tell them whether an assailant is right- or left-handed. “When it comes to beating or stabbing someone to death, we all become switch-hitters,” she explains.

Reading blood evidence in a narrow, absolutist way is a temptation that’s hard to resist. “There’s a frustration level,” Sutton says. “You so want to know what the hell happened. So your mind fills in the blanks. But if you’re a good scientist, you know there are probably alternative explanations, and it’s our job to find them all.”

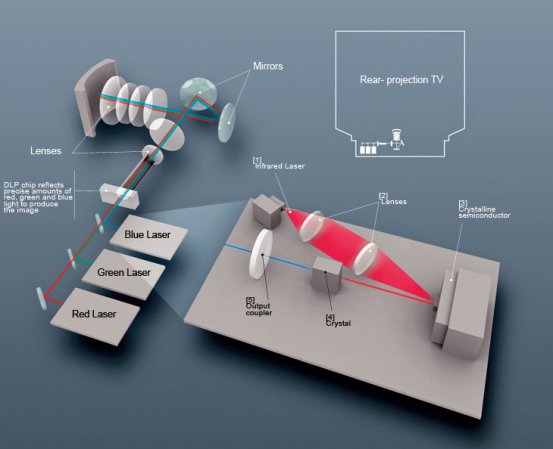

Sutton describes bloodstain-pattern analysis as one part common sense to one part physics and math. A drop of blood, once launched in motion, follows a parabolic (arcing) path until it strikes a surface, where it produces an elongated stain. With some straightforward trigonometry, the ratio of the stain’s width to its length reveals the blood drop’s angle of impact. The angle of impact, in turn, allows the analyst to draw a line back to a projected point of origin. This is the “projected point” that crime scene investigators plot when they run strings or shine laser lights away from multiple bloodstains to a place where the lines intersect. Because a straight line is being used to approximate a parabolic flight path, the bloodstain analyst knows that the actual point of origin has to be at or below the projected point, never above.

In Sutton’s view, this dividing line between the possible and impossible illustrates the true value of bloodstain analysis — it can expose a lie, corroborate an honest accounting of events, and suggest questions.

“There’s nothing I love more than feeding questions to investigators,” says Sutton. “We can lead them, suggest ‘Why don’t you ask him this and that?’ “

The answers can surprise even a veteran. In one of her most disturbing cases, Sutton was approached, in 1999, by defense attorneys representing Shawn Allen Berry, the last of the three men convicted of the infamous, racially motivated Texas dragging murder of James Byrd Jr. The defense hoped that Sutton could corroborate Berry’s claim that he did not participate in Byrd’s murder but had retreated

to the cab of his truck after being threatened by his roommates for trying to stop them. The badly beaten Byrd was chained to and dragged behind Berry’s pickup for three miles, until dismembered. Berry explained the bloodstains on his jeans by saying he got them on the afternoon following the murder, when he helped one of his roommates wash off the blood-drenched truck and chain at Jasper’s Splish-Splash Car Wash.

“I figured I’d just show this guy was lying and be done with it,” Sutton admits. She bought a pile of color-matched, secondhand jeans and spattered them with blood — first with

a rat-trap device designed to replicate the spatter produced by a beating, then with a spray-mist bottle to simulate higher-velocity droplets, such as those spewed from the mouth of a beating victim choking on his own blood. Finally, she attempted to scrub out the blood to see if the large, relatively light bloodstains on Berry’s clothes could have resulted from his attempts to wash off the evidence. “Instead, I found the reverse, that if blood dries on clothes and you then wet it, you get a darker ring around the outside of the stain.”

Next Sutton took more jeans, a heavy length of chain, and a bucket of blood to a local car wash. Sutton hung the pants, their legs stuffed with rolls of paper towel wrapped in plastic, from a floor-mat rack; laid out the bloodied chain in front of them; and hit it with a stream of water from a high-pressure water wand. The resulting back-spatter produced stains that were the same size and intensity as those found on Berry’s pants.

Still skeptical, Sutton shot back questions for the defense attorney to ask his client regarding who did what at the car wash. That’s the beauty of bloodstain evidence, says Sutton. “If he was lying, there would be no way for him to know the ‘right’ answers.”

Berry replied that he had washed off the outside of the truck while roommate Bill King threw away beer cans and pulled the bloodied chain from the flatbed; that he then handed the water wand to King to blast the chain. How close was he to the chain and how much blood was on it? Sutton wanted to know. So close and so much he could smell it, came the reply.

“All his answers matched what I saw,” says Sutton. With mixed emotions, she appeared as a witness for the defense, giving testimony that may have played a large role in the jury sentencing Berry to life in prison, as opposed to the death penalties his two roommates received.