New research is throwing some cold water on the idea that the fearsome Tyrannosaurus rex was as smart as a primate. These possibly scaly-lipped theropods were about as smart as living reptiles like crocodiles, but not quite as intelligent as monkeys. The findings are detailed in a study published April 26 in the journal The Anatomical Record

How smart was the T. rex?

In 2023, a study from Vanderbilt University neuroscientist Suzana Herculano-Houzel set off a dinosaur-sized debate. Herculano-Houzel proposed that dinosaurs like T. rex had an exceptionally high number of neurons–over 3 billion of them, or more than a baboon. This higher number of neurons could mean that they were more intelligent than assumed.

The paper theorized that these high neuron counts could inform their intelligence, metabolism, and even give them some more monkey-like habits. They could have used tools and transmitted knowledge culturally like modern day primates, according to Herculano-Houzel’s study.

These bold claims that such a large and powerful reptilian carnivore could have been intelligent enough to sharpen tools and transmit knowledge shook the paleontology world.

[Related: Is T. rex really three royal species? Paleontologists cast doubt over new claims.]

Taking another look

In this new study, an international team of paleontologists, neuroscientists, and behavioral scientists argues that researchers should look at multiple lines of evidence when reconstructing long-extinct species. These include skeletal anatomy, bone composition, trace fossils that show movement, and the behaviors of their living relatives.

“Determining the intelligence of dinosaurs and other extinct animals is best done using many lines of evidence ranging from gross anatomy to fossil footprints instead of relying on neuron number estimates alone,” study co-author and University of Bristol paleontologist Hady George said in a statement.

The study reexamined the techniques that were used to predict both number of neurons and brain size in dinosaurs as well as decades of previous research. They found that the assumptions made about brain cavity size and corresponding neuron counts were unreliable.

“Neuron counts are not good predictors of cognitive performance, and using them to predict intelligence in long-extinct species can lead to highly misleading interpretations,” Ornella Bertrand, a study co-author and mammalian paleontologist at the Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont said in a statement.

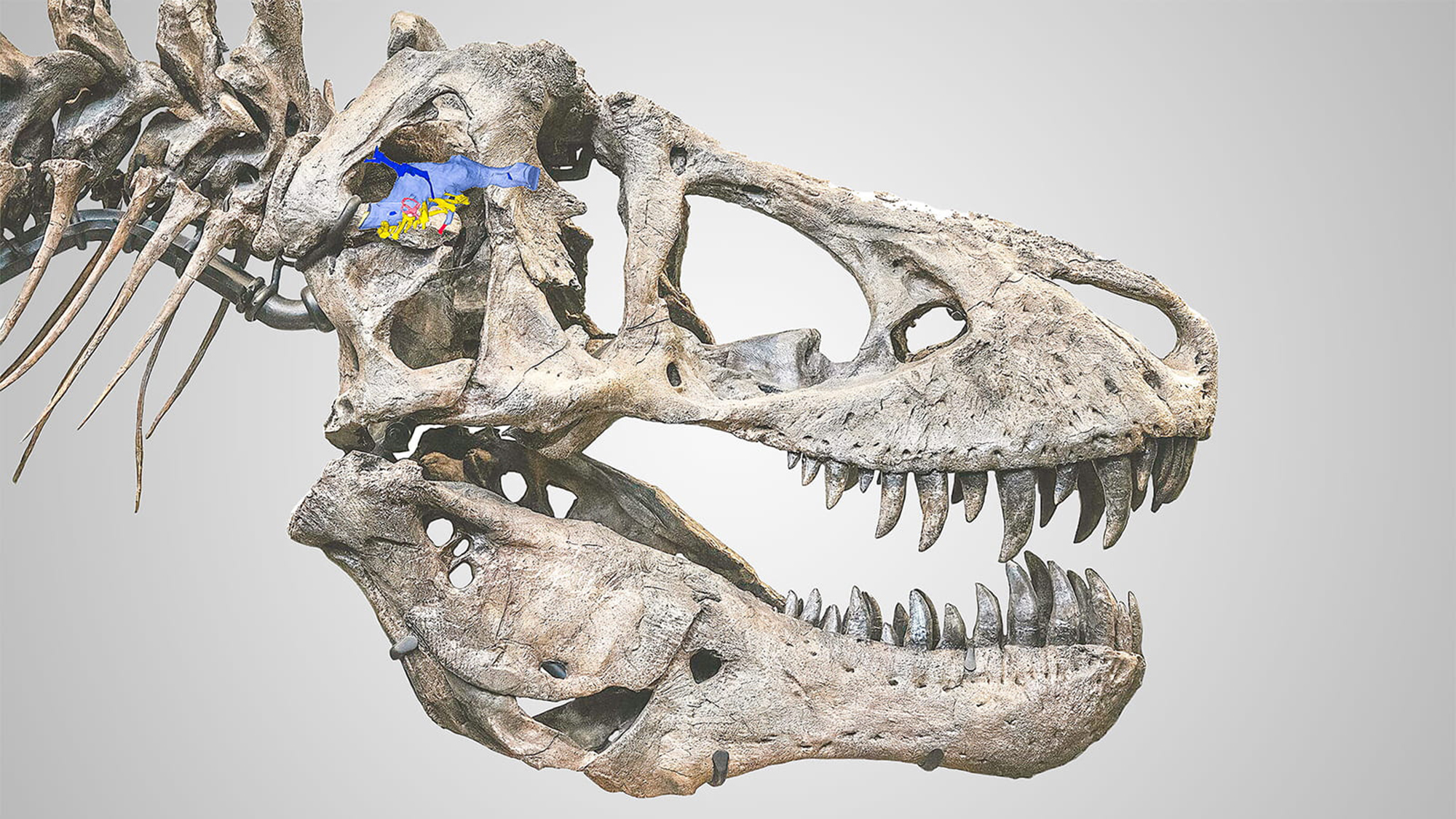

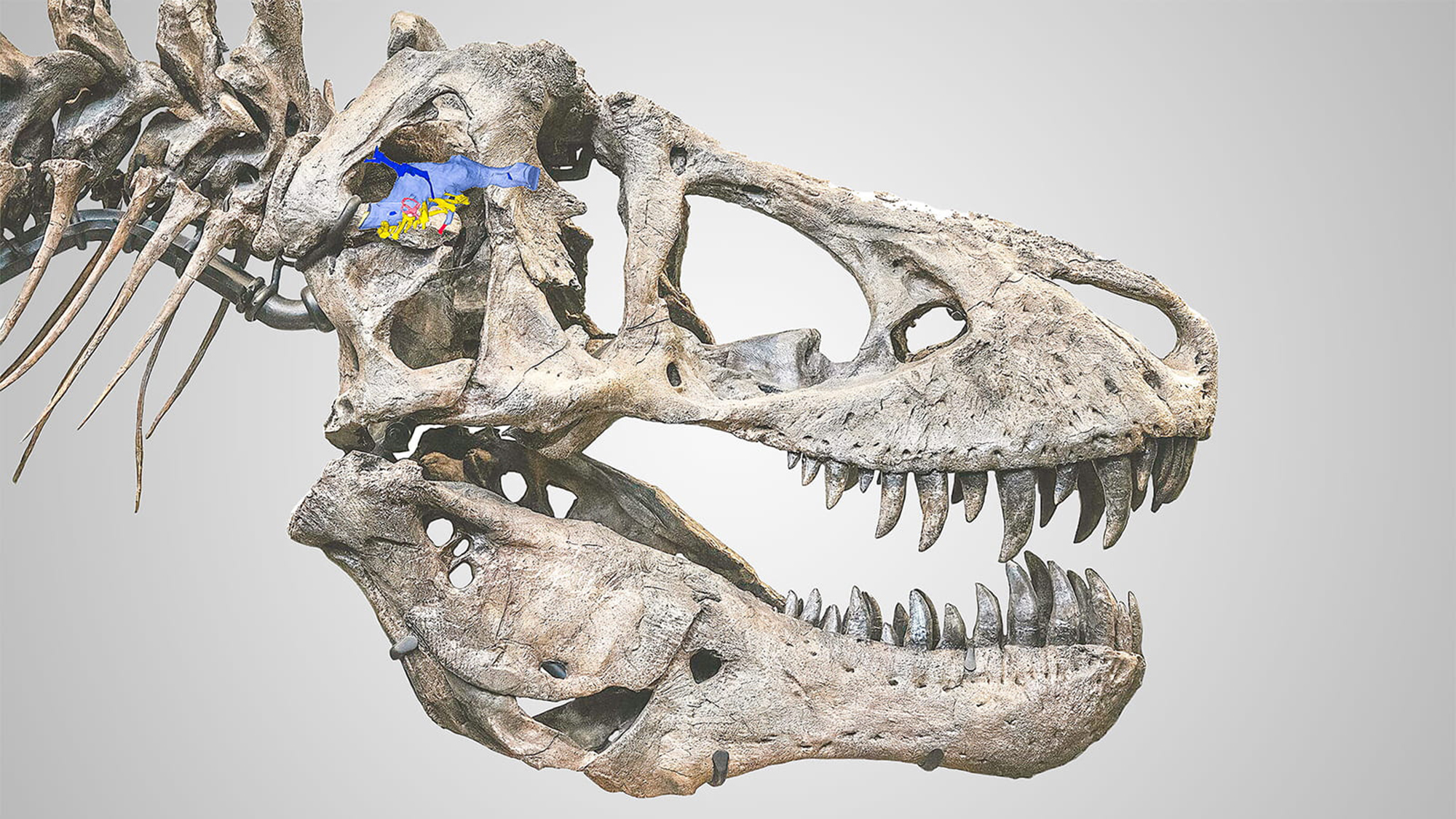

Despite being very similar to big birds, dinosaurs were reptiles. As reptiles, they have very different brains than birds or mammals, but brain tissue does not fossilize. To study what their brains must have been like, scientists look to their skulls for clues. Reptile brains typically don’t fill up their skull cavity and they also tend to have a lot of cerebrospinal fluid taking up space.

“The first time I dissected an alligator brain, I took the top of the skull off and I went, ‘Where is the brain?’ Because there is this big space in there,” study co-author and University of Alberta neurophysiologist Doug Wylie said in a statement.

Reptile brains are also packed more loosely with neurons than bird or mammalian brains. They also don’t have the same kinds of connections and circuits in their brains, which would have limited the complexity of their social behaviors.

Neurons scale up

The size of the animal is also a major factor. An adult male baboon can range from 30 to 88 pounds, while a T. rex could be over 15,000 pounds. Number of neurons typically scales to body size, according to the team.

“We don’t know why it’s true, but it is true,” said study co-author and University of Alberta comparative neurobiologist Cristian Gutierrez-Ibanez said in a statement. “A larger animal needs more neurons.”

[Related: Giganotosaurus vs. T. rex: Who would win in a battle of the big dinosaurs?]

The team believes that the T. rex needed a huge number of neurons for just maintaining basic biological functions with such a large body and wouldn’t have had any leftover for things like cultural knowledge transmission or tool usage.

The study also found that their brain size had been overestimated, particularly the forebrain. The neuron counts could have also been overestimated and the neuron count estimates are not a reliable guide to intelligence.

“The possibility that T. rex might have been as intelligent as a baboon is fascinating and terrifying, with the potential to reinvent our view of the past,” study co-author and University of Southampton palaeozoologist Darren Naish said in a statement. “But our study shows how all the data we have is against this idea. They were more like smart giant crocodiles, and that’s just as fascinating.”

In response to this new study re-examining her work, Herculano-Houzel told the Los Angeles Times, “I am delighted to see that my simple study using solid data published by paleontologists opened the way for new studies. Readers should analyze the evidence and draw their own conclusions. That’s what science is about!”