Scavenging has been maligned as a food gathering strategy and is generally associated with animals like vultures and hyenas. Millions of years ago, carnivorous dinosaurs may have evolved this technique of taking meat from dead carcasses too. The findings are described in a study published November 1 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE.

[Related: Dinosaur cannibalism was real, and Colorado paleontologists have the bones to prove it.]

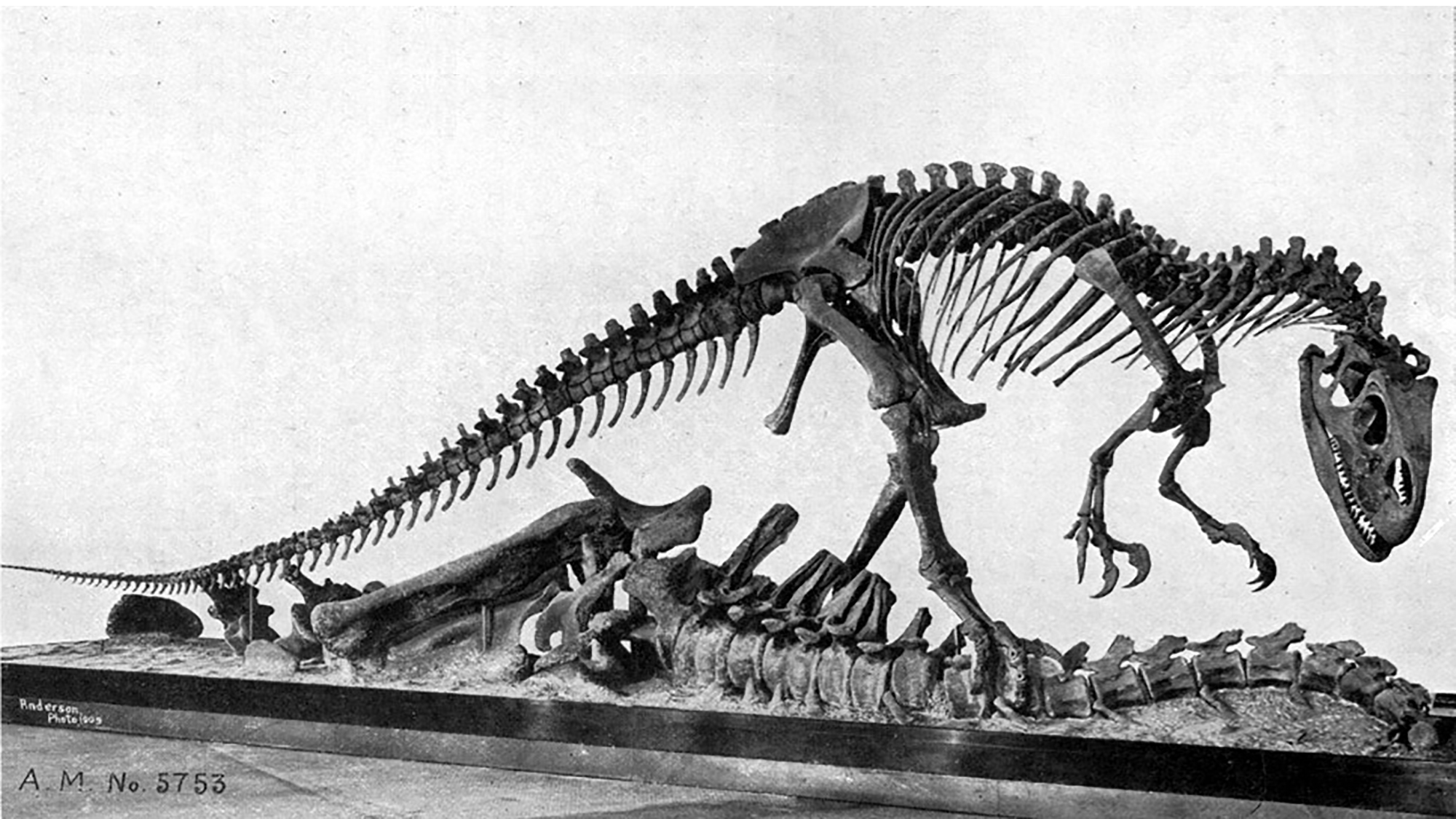

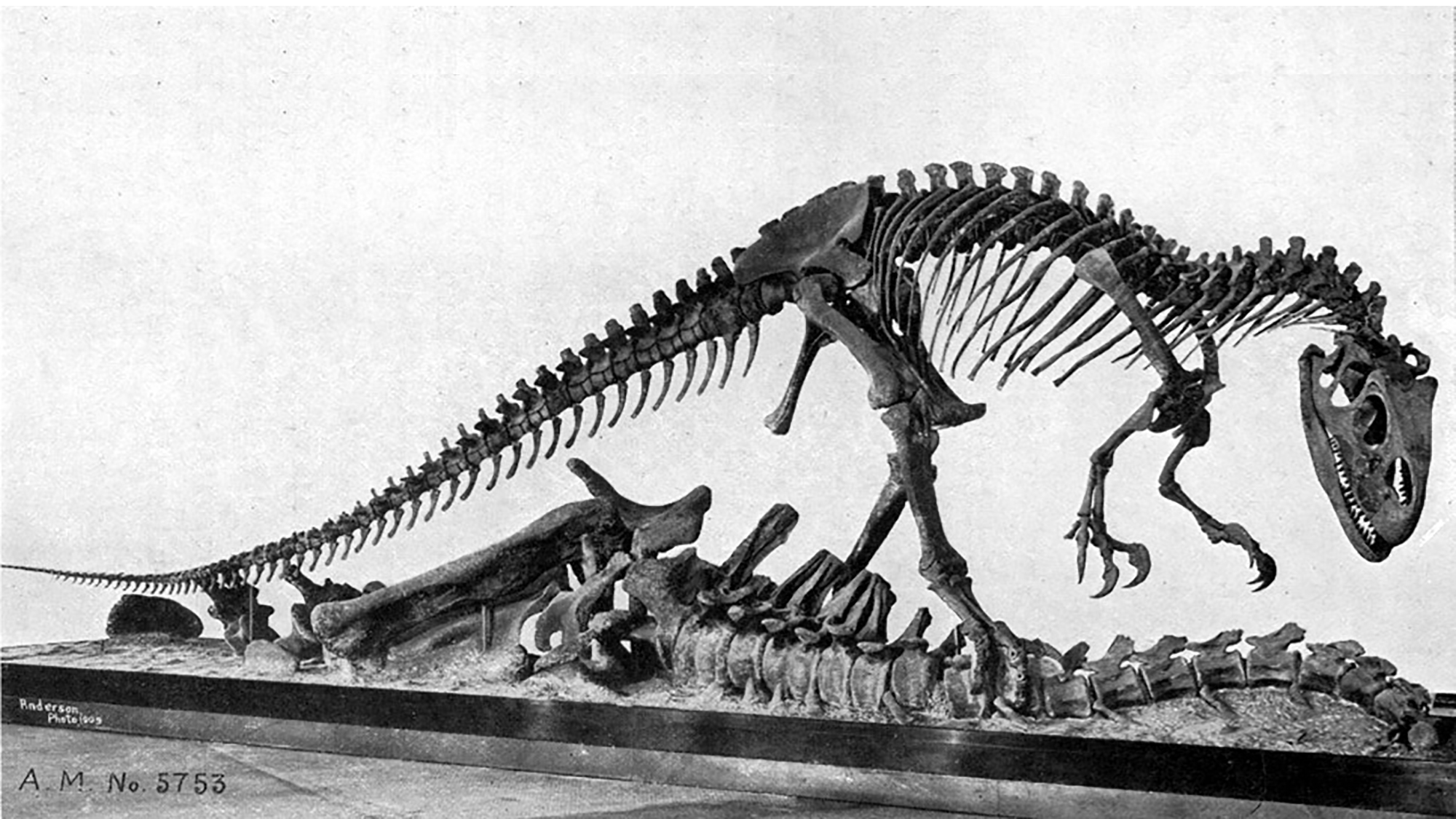

Carnivorous dinosaurs like the cannibalistic Allosaurus were surrounded by both living and dead prey. The bodies of large sauropod dinosaurs, some of whom could weigh more than 500,000 pounds, could have provided an important food source for carnivores.

In this study, a team of researchers from Portland State University created a simplified computer simulation of a dinosaur ecosystem from the Jurassic age. They used the animals that have been found in the 163.5 to 145 million year-old Morrison Formation in the western United States as the basis. This enormous fossil formation was once home to a wide variety of plants and dinosaurs.

The model included large carnivores common to the area like Allosaurus, large sauropods and their carcasses, and a large group of living and huntable Stegosaurus’. The carnivores were assigned traits that would improve their hunting abilities with the energy from living meat sources or their scavenging abilities with the sustenance from the carcasses. The model then measured the evolutionary fitness of the simulated predators.

The model found that when there were a large amount of sauropod carcasses around, scavenging was more profitable than hunting for the Allosaurus. Meat eaters in these kinds of ecosystems may have evolved specialized traits to help them detect and exploit these large carcasses.

“Our evolutionary model demonstrates that large theropods such as Allosaurus could have evolved to subsist on sauropod carrion as their primary resource,” the authors wrote in a statement. “Even when huntable prey was available to them, selection pressure favored the scavengers, while the predators suffered from lower fitness.”

[Related: This 30-pound eagle would take down 400-pound prey and dig through their organs.]

This model represents only a simplified depiction of a complex ecosystem, so more variables like additional dinosaur species may alter the results. While theoretical, using models like this one can help scientists better understand how the availability of meat from carcasses can influence how predators evolve. A September 2023 modeling study found that even early humans living in southern Europe roughly 1.2 to 0.8 million years ago were scavengers. They may have competed in groups of five or more to fight off extinct giant hyenas for the carcasses of animals that had been abandoned by larger predators like saber-toothed cats.

“We think allosaurs probably waited until a bunch of sauropods died in the dry season, feasted on their carcasses, stored the fat in their tails, then waited until the next season to repeat the process,” the authors wrote. “This makes sense logically too, because a single sauropod carcass had enough calories to sustain 25 or so allosaurs for weeks or even months, and sauropods were often the most abundant dinosaurs in the environment.”