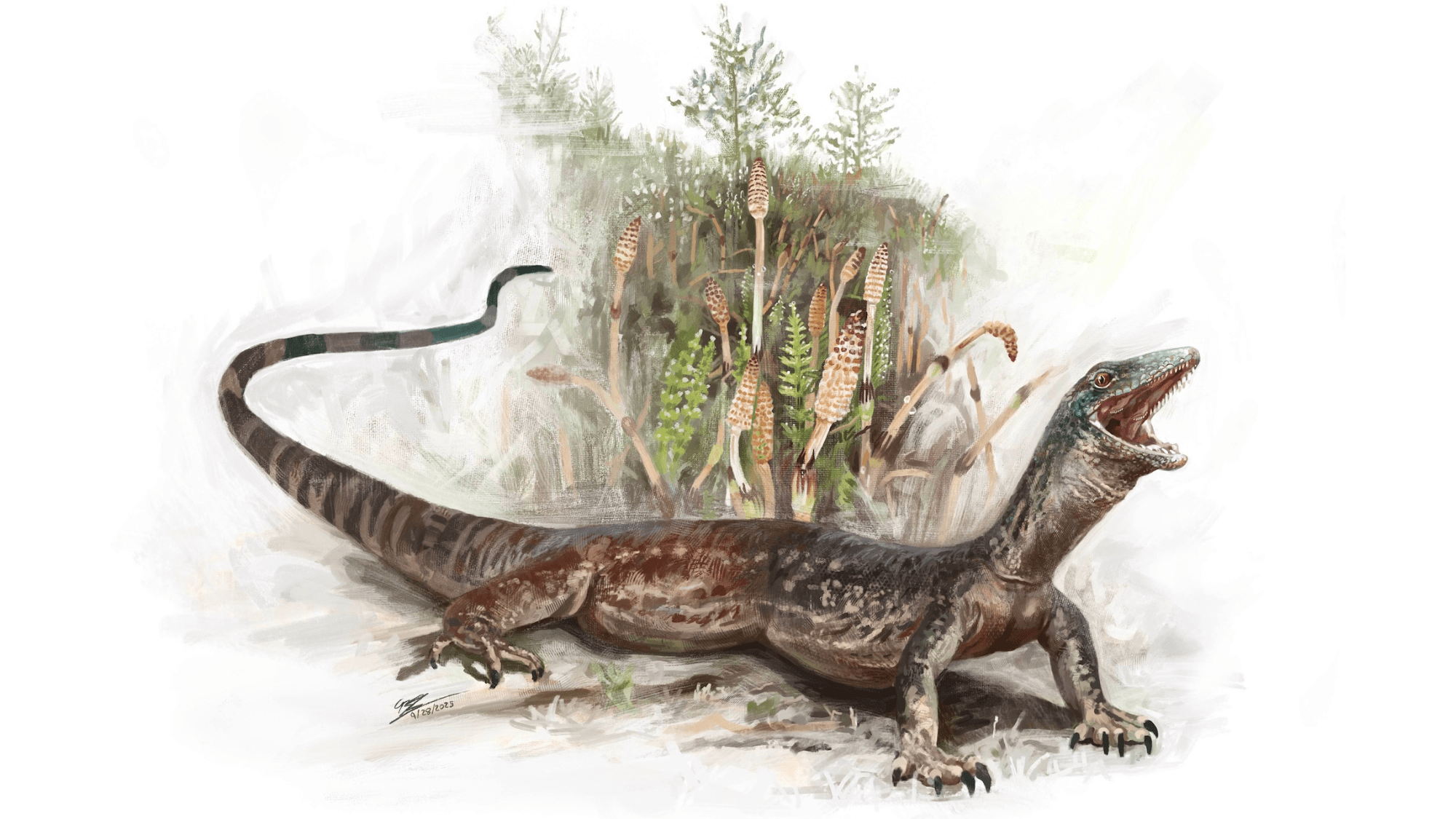

What do you get when you cross a snake with a lizard? The answer isn’t a punchline. It’s a newly discovered creature from the Jurassic Period, whose name is a tribute to its confusing physical characteristics. As paleontologists explained in a study published on October 1 in Nature, the “false snake of Elgol” featured the jaws and hooked teeth of a python, along with the short body and stubby legs of a gecko.

The announcement of Breugnathair elgolensis is the culmination of nearly a decade’s worth of work, after an international research team discovered the specimen on the fossil-rich Isle of Skye. Located off Scotland’s western coast, the island’s fossil deposits span millions of years and include ancient branches of the lizard family tree.

“The Jurassic fossil deposits on the Isle of Skye are of world importance for our understanding of the early evolution of many living groups, including lizards, which were beginning their diversification at around this time,” University College London paleontologist and study co-author Susan Evans explained in a statement.

Given the vast differences between the bone fragments, Evans and her colleagues initially believed that the remnants belonged to two separate species of squamates—the taxonomical group composed of lizards and snakes. After years of detailed analysis, paleontologists determined that B. elgolensis falls into a lesser known group of predatory squamates called Parviraptoridae.

“I first described parviraptorids some 30 years ago based on more fragmentary material, so it’s a bit like finding the top of the jigsaw box many years after you puzzled out the original picture from a handful of pieces,” said Evans.

At around 167 million years’ old, this particular B. elgolensis is one of the oldest, surprisingly complete reptile fossils ever seen. The creature measured about 16 inches long, making it about the size of a small cat and one of the largest lizards in its domain. B. elgolensis likely used its curved, snakelike teeth and jaw structure to prey on smaller lizards, mammals, and possibly even young dinosaurs. But despite these formidable serpent features, study co-author Roger Benson from the American Museum of Natural History in New York describes B. elgolensis as “surprisingly primitive.”

“This might be telling us that snake ancestors were very different to what we expected, or it could instead be evidence that snake-like predatory habits evolved separately in a primitive, extinct group,” he added.

For now, these unique characteristics leave B. elgolensis’ evolutionary trajectory a mystery. Early squamates are extremely rare in the fossil record, making it difficult for experts to rule one way or another. Benson and Evans also theorize that the animal could represent a stem-squamate, the predecessors to all snakes and lizards. If this proves to be true, B. elgolensis may have independently evolved its distinctive jaws and teeth.

“This fossil gets us quite far, but it doesn’t get us all of the way,” said Benson. “However, it makes us even more excited about the possibility of figuring out where snakes come from.”

B. elgolensis also shows how messy evolution can be, and that the path from one species to another is not always so clear cut.

“The mosaic of primitive and specialized features we find in parviraptorids, as demonstrated by this new specimen, is an important reminder that evolutionary paths can be unpredictable,” Evans added.