Most people use the terms “optical illusion” and “visual illusion” interchangeably. “That’s a pet peeve of mine,” says Pascal Wallisch, a neuroscientist and psychology professor at New York University who has studied the viral phenomenon known as The Dress. “There is a profound and metaphysical difference between the two.”

Optical illusions are tricks of the light. For example, if you plunge a stick in the water, it will appear crooked because of the way light bends—even though, in reality, the stick is straight. Or, in the desert, when the ground is hot, and air is cool, and there is air turbulence, it might cause a shimmer at the horizon that looks like a pool of water. It’s about physics.

In contrast, a visual illusion occurs in your brain, explains Wallish. Your own brain systems, which are constantly interpreting information, are creating the effect. “What you see isn’t what you get,” he says. “Your brain is interpreting and heavily editing all the information coming in. A visual illusion is a profound misunderstanding; it’s a fundamental misrepresentation.”

Visual illusions raise questions about how our brains work and threaten our view of reality. “These visual illusions are real,” Wallisch says. “And we have a pretty good idea in many cases how the brain does this.” Below, Wallisch breaks down why these illusions fascinate the mind. Then, you can shop each of these captivating images along with thousands more optical illusions on Fine Art America.

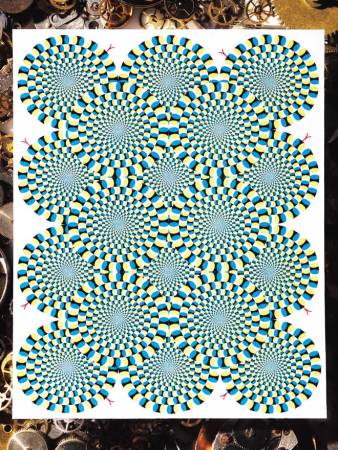

The snake-like swirls look like they are moving. “This phenomenon rests on apparent motion, which is the basis of all video,” says Wallisch. A refresher: Films are shot at a rate of 24 frames per second. But when you watch a movie, you don’t see 24 individual images. “The motion is not there,” says Wallisch. “Your brain is filling in the gap—it infers motion between two images.”

It takes 100 milliseconds (one-tenth of a second) for the signals coming from the retina to reach the brain. And the more contrast, the faster the transmission. For example, a high-contrast signal will arrive a twentieth of a second faster than a low-contrast signal. So, in the above visual illusion, the gradient of contrasts is arranged so that the brain infers motion: “The high-contrast parts arrive a touch quicker than the rest.”

Your eyes are in constant motion, says Wallisch. But when you look in the mirror, you can’t see your own eye movements. (You only see yourself staring at yourself.) However, suppose you ask a friend to track your eye movements. They’ll tell you that your eyes are darting around continuously.

Your brain takes this visual input and essentially “edits” them together, similar to a jump cut in a movie, explains Wallisch. For example, in the illusion above, your brain uses the lined background as a reference point to orient the heart. And since your eyes are constantly moving, it makes it appear that the heart is throbbing.

Developed by German psychologists, the Gestalt laws describe how we interpret the world around us. For example, when we look around, we usually perceive complex scenes composed of many objects on some background. The objects themselves consist of parts, which may be composed of smaller pieces.

According to the Law of Pragnanz of the Gestalt (also known as the law of good figure or the law of simplicity), when people are presented with a set of ambiguous or complex objects, your brain will make them appear as simple as possible. “What’s more likely?” Wallisch asks about the above illusion, “That there are two triangles or there is a weird figure that can’t exist in 3-D? You see the closed triangles.”

In the illusion above, the two red circles are actually the same size. That’s because perception isn’t absolute, says Wallisch. Things are judged by context. Since the black circles on the left are smaller than the red circle, the red circle appears larger. The opposite is true when the same red circle is surrounded by much larger black circles on the right.

“Your consciousness can only do one thing at a time,” says Wallisch. This famous Ruben’s vase image above is actually an “image segmentation” problem.

Your brain either sees two faces or a vase—it’s impossible to see both at the same time. In essence, your mind has to decide which color is the figure and the background. If you assume that the white portion is the figure and the black part is the background, you see a vase. If you consider the black piece as the figure and the white portion as the background, you see two faces. “Your brain has to reconstruct what is out there and make assumptions,” Wallisch says.