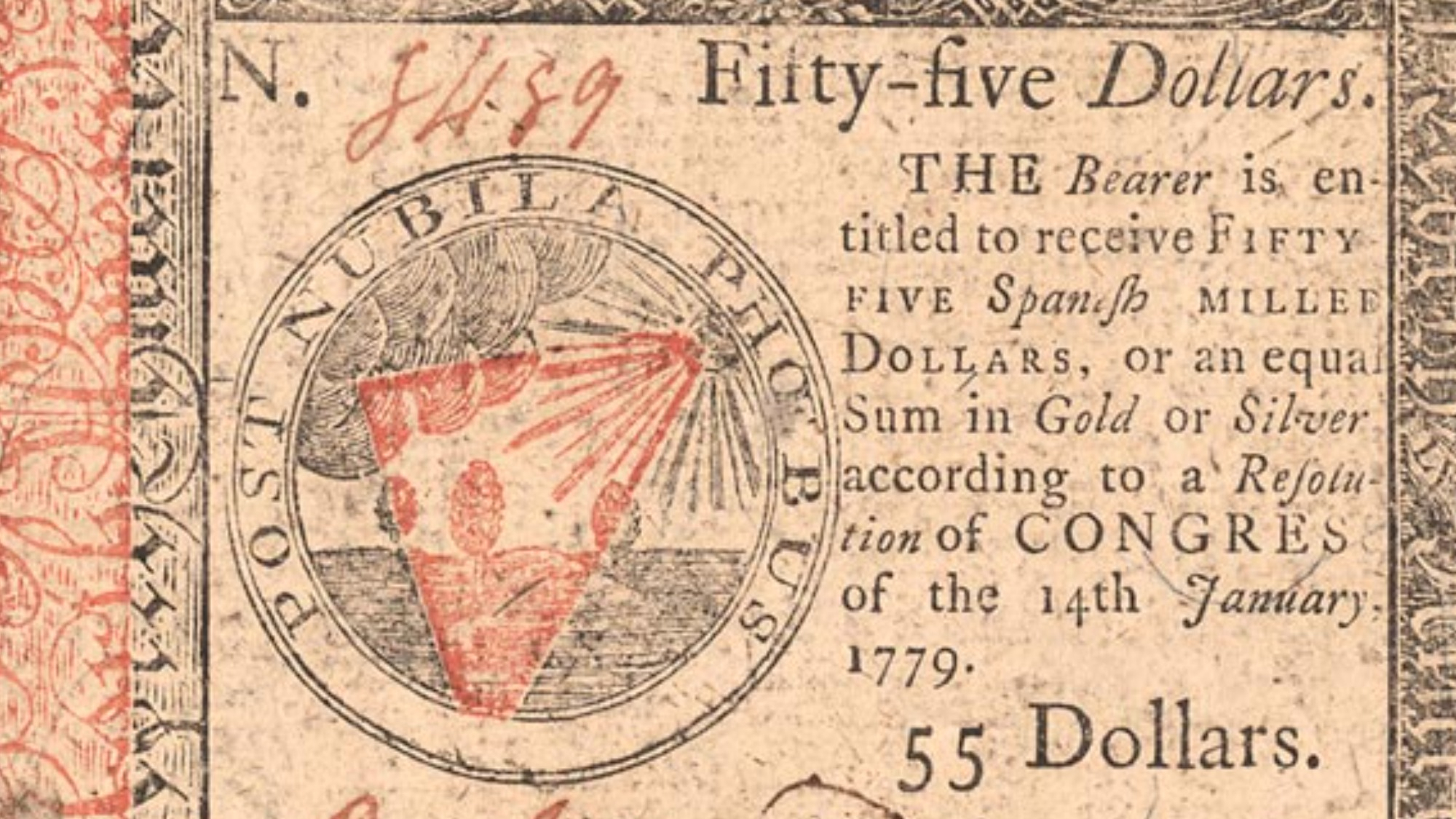

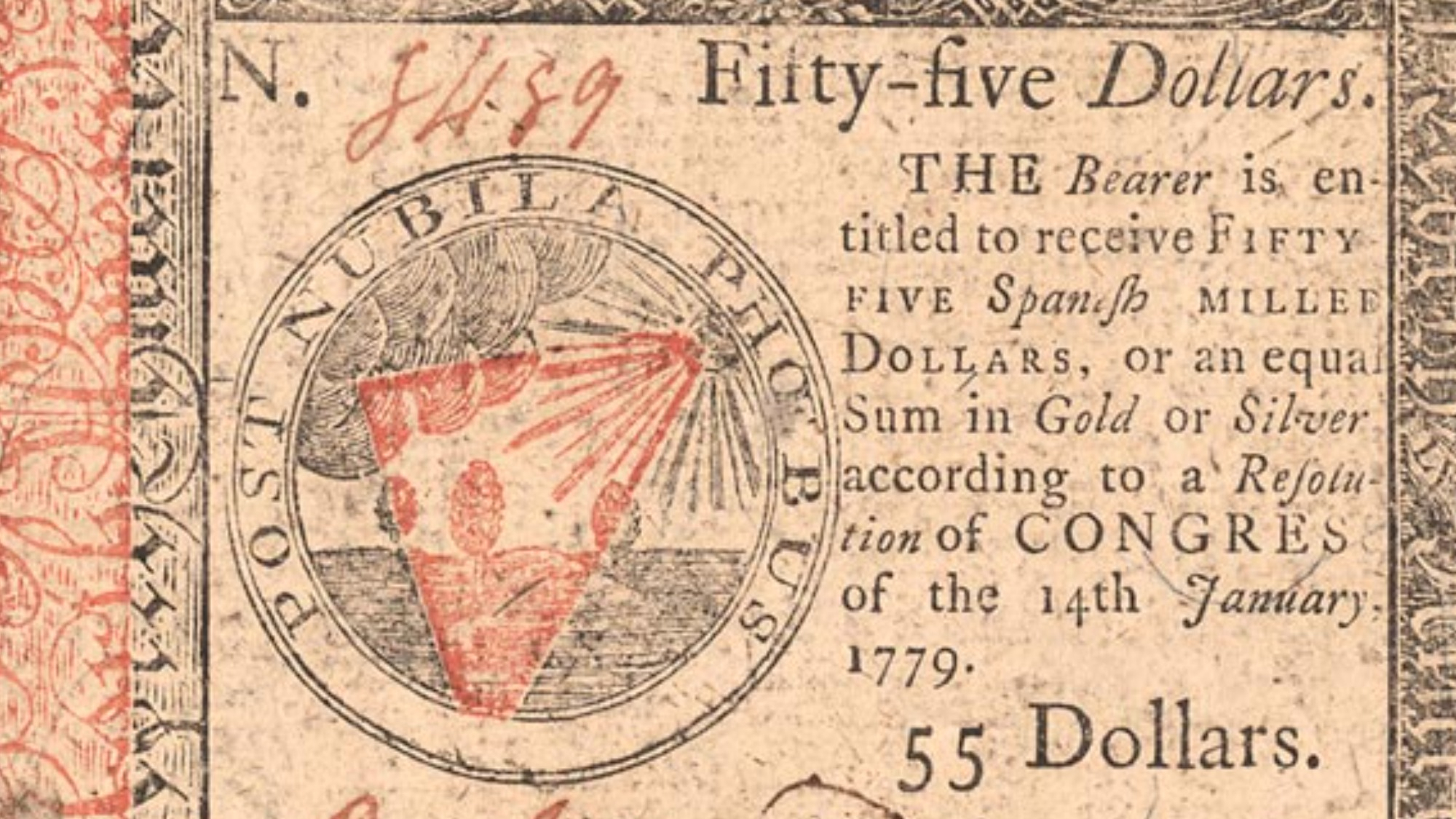

When he wasn’t busy inventing the lightning rod and bifocals, electrocuting turkeys, or serving as a diplomat to France during the American Revolution, 18th century polymath Benjamin Franklin was also innovating the printing of paper money. A study published July 17 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) found that Franklin may have printed almost 2,500,000 money notes for the colonies that would become eventually become the United States’ currency. And he came up with some highly original techniques to do it.

[Related: What exactly is a digital dollar, and how would it work?]

The study team analyzed about 600 notes from between 1709 through the 1790s, including some notes that Franklin printed in his network of printing shops, as well as some counterfeits.

“Benjamin Franklin saw that the Colonies’ financial independence was necessary for their political independence. Most of the silver and gold coins brought to the British American colonies were rapidly drained away to pay for manufactured goods imported from abroad, leaving the Colonies without sufficient monetary supply to expand their economy,” study co-author and physicist at the University of Notre Dame Khachatur Manukyan said in a statement.

Counterfeiting was a major roadblock in the efforts to print paper money in the Thirteen Colonies. Currency has evolved over time, and while the earliest known paper money dates back to the Tang Dynasty in China (CE 618–907), paper notes were a relatively new concept in the Colonies when Franklin opened his printing house in 1728. Without traditional gold or silver, paper money’s lack of value meant it was at risk of depreciating. The Colonial period had no standardized bills, so counterfeiters had plenty of opportunities to use fake notes as real ones.

To combat this, Franklin developed security features that made his bills a bit more distinct.

“To maintain the notes’ dependability, Franklin had to stay a step ahead of counterfeiters,” said Manukyan. “But the ledger where we know he recorded these printing decisions and methods has been lost to history. Using the techniques of physics, we have been able to restore, in part, some of what that record would have shown.”

In the study, the team used spectroscopic and imaging instruments to take a closer look at the fibers, inks, and paper that made Franklin’s bills stand out—and made them difficult to replicate. They found that pigments Franklin used were more distinctive, with the counterfeit gills having high quantities of calcium and phosphorus, but those materials only being found in traces on genuine Franklin bills.

While Franklin used a pigment created by burning vegetable oils called lamp black for most of his printing, he used a special black dye made from graphite in his currency. This pigment is also different from one called bone black, made from burned bones and favored by counterfeiters and those outside of Franklin’s printing house network.

[Related: Fake Galileo manuscript suspected to be a 20th-century forgery.]

The paper printed by Franklin’s network also has a distinctive look due a translucent material they identified as muscovite. The study team speculates that adding muscovite initially began to make Franklin’s printed notes more durable, and continued when it was a helpful counterfeit deterrent.

According to Manukyan, it is unusual for a physics lab to work with rare and archival materials, and this posed special challenges, but turned out to be a testament to the importance of interdisciplinary work.

“Few scientists are interested in working with materials like these. In some cases, these bills are one-of-a-kind. They must be handled with extreme care, and they cannot be damaged. Those are constraints that would turn many physicists off to a project like this,” he said.