A couple of decades before he founded Popular Science, Edward Livingston Youmans published a book called Youmans’ Atlas of Chemistry. Youmans was not a chemist, but he was a good writer whose singular passion in life was to learn everything there was to know about everything, and his textbook was probably the most readable thing anyone had ever published on the subject.

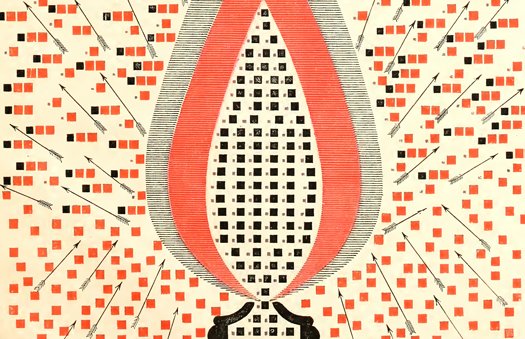

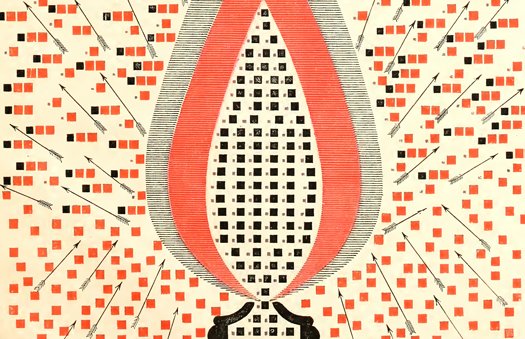

But what made Youmans’s Atlas really stand out were the illustrations–a series of simple, beautiful diagrams that give form and substance to the invisible world of atomic chemistry. Clearly, Youmans understood–in a way today’s textbook writers don’t seem to–the difficulty students might have trying to understand things they couldn’t see. Which makes sense, actually: Youmans spent much of his life, including his years studying chemistry, in a state of near-total darkness. Who could know the importance of visualization better than a blind man?

In a short biography of Youmans’s life, published in the March 1887 issue of PopSci, Youmans’s sister Eliza Ann writes of an eye disease that struck Edward at the age of 13. Probably, it was the sort of infection that modern antibiotics could easily cure, but in Youmans’ time there was nothing for it, and Edward suffered from episodic bouts of painful inflammation and impaired vision for the rest of his life. When he was 20 years old, Youmans left his family home in rural New York State and went to the city in search of a cure, but shortly afterward his sight deteriorated completely; it was twelve years before he could see well enough to read.

During that time, Eliza Ann went to care for her brother in the city, and found a chemistry professor who would admit her (a woman) into his courses; she passed everything she learned on to Edward. “After this we could manage the subject fairly well together,” she writes, “but, unable as he was to observe the characteristic behavior of chemical substances, he could not readily individualize them. His ideas about them, therefore, were easily confused, and he was constantly striving to make them more definite.”

After years of acquiring second-hand knowledge of chemistry, it occurred to Youmans that he was not entirely alone–sure, most people could mix acids and bases together and watch the results, but much of chemistry dealt with things on a much smaller scale. When it came down to the atoms and molecules whose reactions lay behind all the fizzing and burning and exploding ingredients, all the other students were just as blind as he.

According to Eliza Ann, it was this realization that inspired Youmans to invent “a scheme for picturing atoms and their combinations that would bring the eye of the student into more effectual service.” These lovely illustrations are the result:

[h/t Brainpickings]