For many years, a Chinese man in the U.K. experienced a range of debilitating neurological symptoms with no understood origin–including headaches, memory loss, and seizures. A biopsy found inflammation in the man’s brain, but they were unable to pinpoint the exact cause of his symptoms.

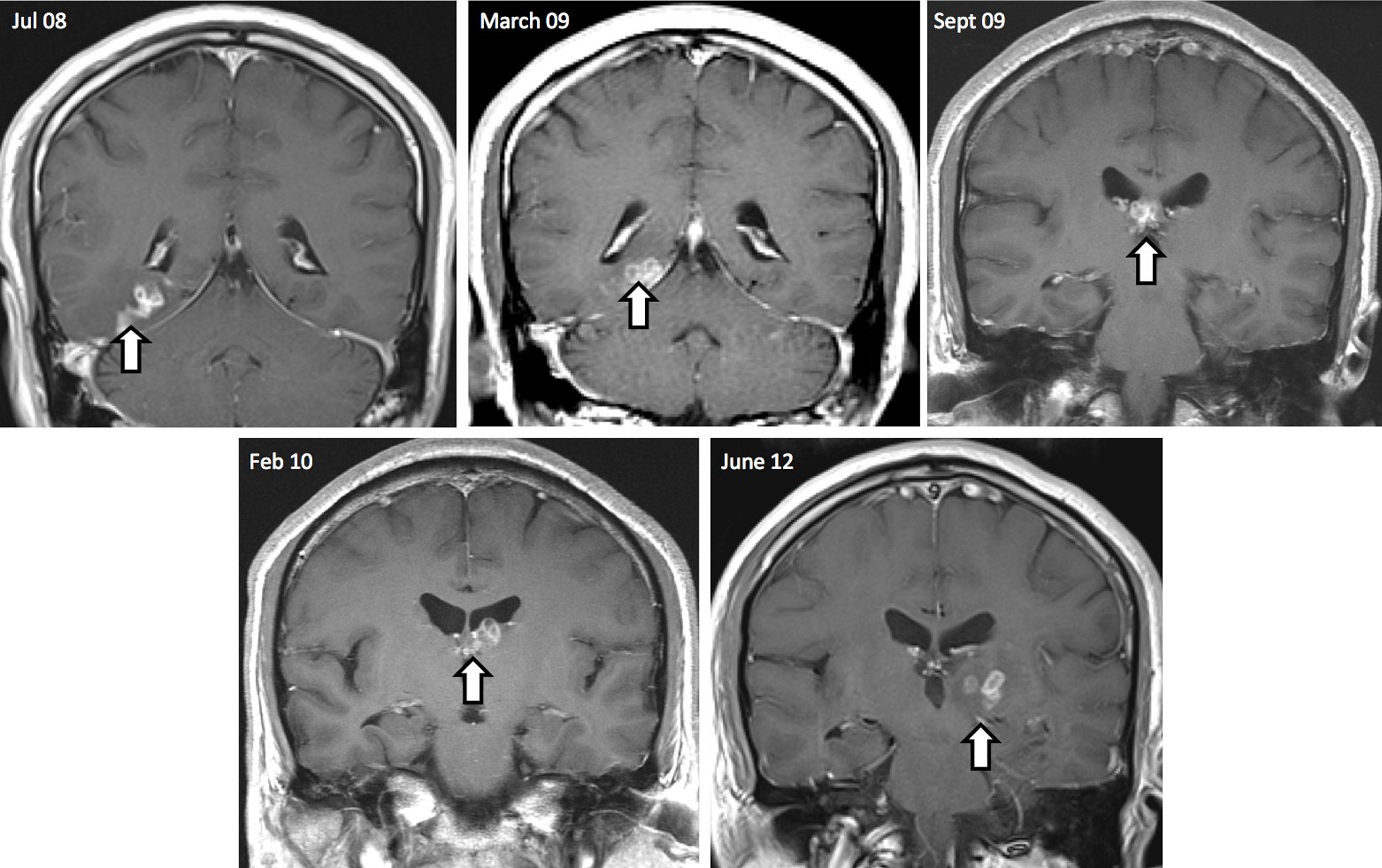

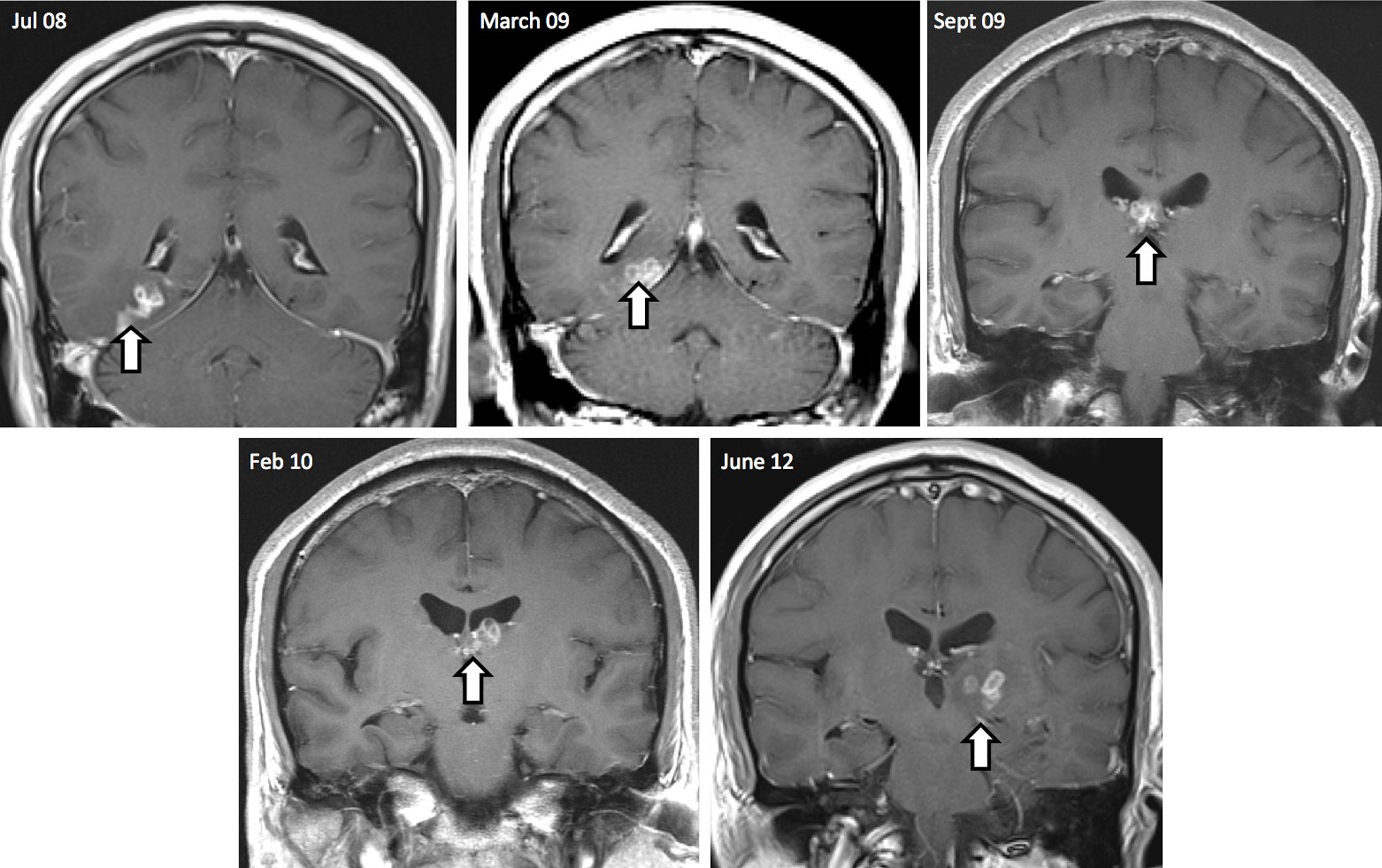

Then in one final biopsy, surgeons unearthed the source of the man’s neurological issues; they pulled out a tapeworm that had been crawling through the patient’s brain for the past four years. The centimeter-long parasite had travelled more than 2 inches from the right side of his brain to the left, before it was successfully removed through surgery. Now, the patient is doing just fine.

Researchers from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute successfully mapped the genome of this man’s particular tapeworm, revealing it to be an extremely rare species known as Spirometra erinaceieuropaei. It marked the first time this species of tapeworm had ever been sequenced, and researchers hope its genetic information will help clinicians better diagnose and treat this parasite infection and others like it in the future.

To feed, it absorbs fats through its skin. Fortunately for the worm, our brains are full of fatty acids on which to munch.

According to Dr. Hayley Bennett, lead researcher on the project, Spirometra erinaceieuropaei infection is seldom seen in humans. “Before 2003, there was only 300 cases reported in the literature, predominantly in China and Southeast Asia,” Bennett tells Popular Science. The parasite lives in water, and it’s believed that people become exposed to the parasite by eating infected crustaceans or raw meat from amphibians and reptiles. It’s also possible that human infection occurs when people apply poultices of raw frog meat to their eyes – a traditional Chinese remedy.

In the human brain, Spirometra erinaceieuropaei causes inflammation of the body’s tissues, which results in headaches and seizures. And to feed, it absorbs fats through its skin. Fortunately for the worm, our brains are full of fatty acids on which to munch.

When examining the tapeworm’s genome, the researchers found it to be much larger than expected. “It’s 1.26 billion base pairs (Gb) long, which is almost comparative to the human genome,” says Bennett. “We don’t know why the genome is so large, but we looked for repetitive sequencing in the genome, and we found the repetitions make up quite a large percentage.” Spirometra erinaceieuropaei‘s genome is around 10 times larger than other tapeworms that have been sequenced, and it is filled with many genetic sequences that help it to break up proteins and easily invade its host.

More importantly, the research indicates that the tapeworm is resistant to albendazole, a widely used anti-tapeworm drug. Now with this tapeworm’s genome mapped, researchers can pinpoint new drug targets in the worm that might be effective – both for Spirometra erinaceieuropaei and other tapeworms like it.

Bennett says this researcher highlights the need for the sequencing of more tapeworms, in order to create a global database of parasites and their genetic information. Such a database would go a long way in helping doctors to both identify and treat these parasitic pests, which prove to be a substantial problem across the globe.

“From a clinical perspective, tapeworms are a big problem all over the world. They are the largest cause of preventable epilepsy in developing countries,” says Bennett. “We hope the genome we produced will help people decide what kind of worm they get, but we’re just scratching the surface at the moment.”

The researchers published their work in Genome Biology.