Fossil Discovery Could Help Today’s Endangered River Dolphins

A remarkable find, now in 3D.

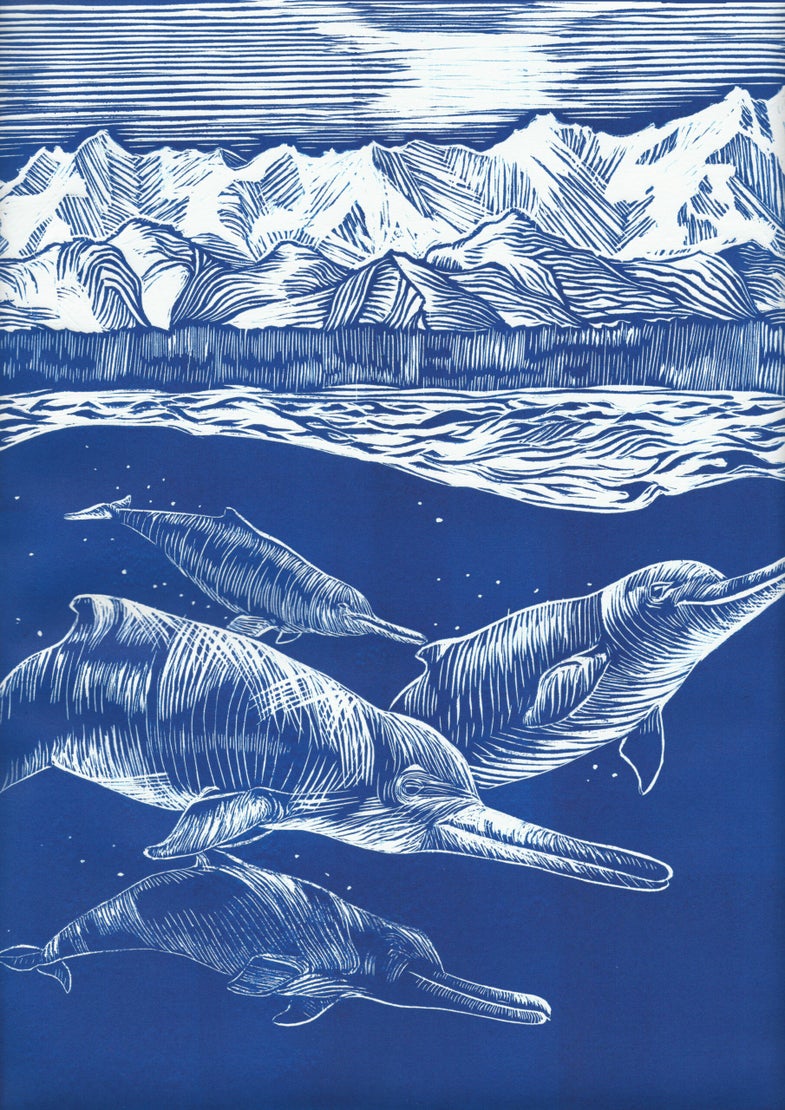

What swims on its side, is blind, and lives in some of the most polluted rivers in the world?

Unlike the more than 30 species of oceanic dolphins, the South Asian River Dolphin is unique, or “tremendously bizarre” as Smithsonian marine mammal fossil curator Nicholas Pyenson puts it. But because of its polluted habitat, overfishing and other human-caused environmental pressures, the already rare dolphins are endangered.

But a new find hiding in the 40-million-specimen Smithsonian paleobiology collection may hold some clues about how to best protect this unique cetacean by uncovering its evolutionary past.

The new findings by Pyenson and researcher Alex Boersma show that a skull found in southeast Alaska by a United States Geological Survey geologist in 1951, is a new genus and species of dolphin that lived in subarctic ocean waters around 25 million years ago. Arktocara yakataga is one of the closest relatives to the modern South Asian River Dolphin.

An ancient relative

Yet Arktocara yakataga is not the only species to be found that is closely related to the South Asian River Dolphin, or Platanista gangetica. Many similar species once swam around the world, though the remnants can now only be found in the fossil record, and in their present day freshwater descendants.

“All the other twigs of the tree are dead, and this is the only one that’s survived,” says Pyenson.

Pyenson believes that more study, and new finds like this one, could help the current species, which only lives in rivers in the South Asian subcontinent. Once considered two species, the Indus river dolphin and the Ganges river dolphin are now considered subspecies of Platanista. There are less than 2,000 in the world.

The modern counterpart

“Knowing more about the history could help us to better be able to make priorities in modern times,” says Pyenson. Understanding why these toothed dolphins were “supplanted by ocean dolphins,” dwindling down to one species, could change our conservation techniques for the better, he says.

Pyenson says that it is a possibility that the other similar species did not have the same echolocation sensibilities that have allowed Platanista to survive. Or they could have just been outcompeted by modern oceanic dolphins.

Whatever the reasons for the ancient extinctions may be, more research could bring hope for this modern species that is inching toward extinction. The past may be a window for the future.

A new find