Google’s Most Ambitious Life Sciences Projects Are Struggling To Launch

Despite the grand ideas, the science of Verily may not be there yet

Three years ago, Andrew Conrad, an executive at Google’s then biotech venture which would eventually become Verily, proposed an idea for a device similar to the fictional Tricorder in Star Trek that would use nanoparticles for early cancer detection. With a huge amount of money to back them up, he said his team would have a working prototype within 6 months, yet three years later, there was still no device. Now, an investigation by Stat, shows that three ideas set forth by Google’s new life sciences subsidiary, Verily, might never see reality.

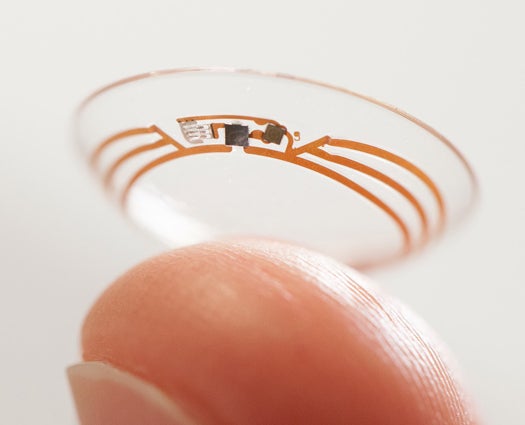

In addition to the cancer detector, other ideas, including much hyped contact lenses capable of sensing glucose to help diabetics, as revolutionary as they might sound, might not have the science data to back them up. And according to Stat, that might have to do with the way the company approaches its research, by routinely using the Silicon Valley model of: “Boast now, build later.”

One of Google’s main goals with Verily is to combine big data and advances in technology with science in an attempt to cure diseases. However scientists around the country have questioned the validity of this idea. One of the larger issues that some scientists take with how some initiatives at Verily run, is that a scientific idea, no matter how important or exciting it is, without a clear path on how to achieve it is rarely successful.

If Google wants to continue to position itself as a leader in the life sciences, it may have to alter the way it approaches big ideas, like curing cancer.

Read the full report here at Stat.