The pandemic could be a long-awaited turning point for telemedicine

100 years ago, doctors sent a heartbeat over a phone line, but devices enabling remote care may have finally found their moment

From cities in the sky to robot butlers, futuristic visions fill the history of PopSci. In the Are we there yet? column we check in on progress towards our most ambitious promises. Read more from the series here.

The stethoscope was born in 1816 in a fit of self-consciousness. To avoid having to press his ear directly on a patient’s ample chest, French physician René Theophile Hyacinthe Laënnec resorted to a rolled-up sheet of paper to listen to an ailing woman’s heart. Laënnec pioneered the practice of listening to sounds made by internal organs (or auscultation), and that prudent moment also triggered a wave of innovation that’s still underway.

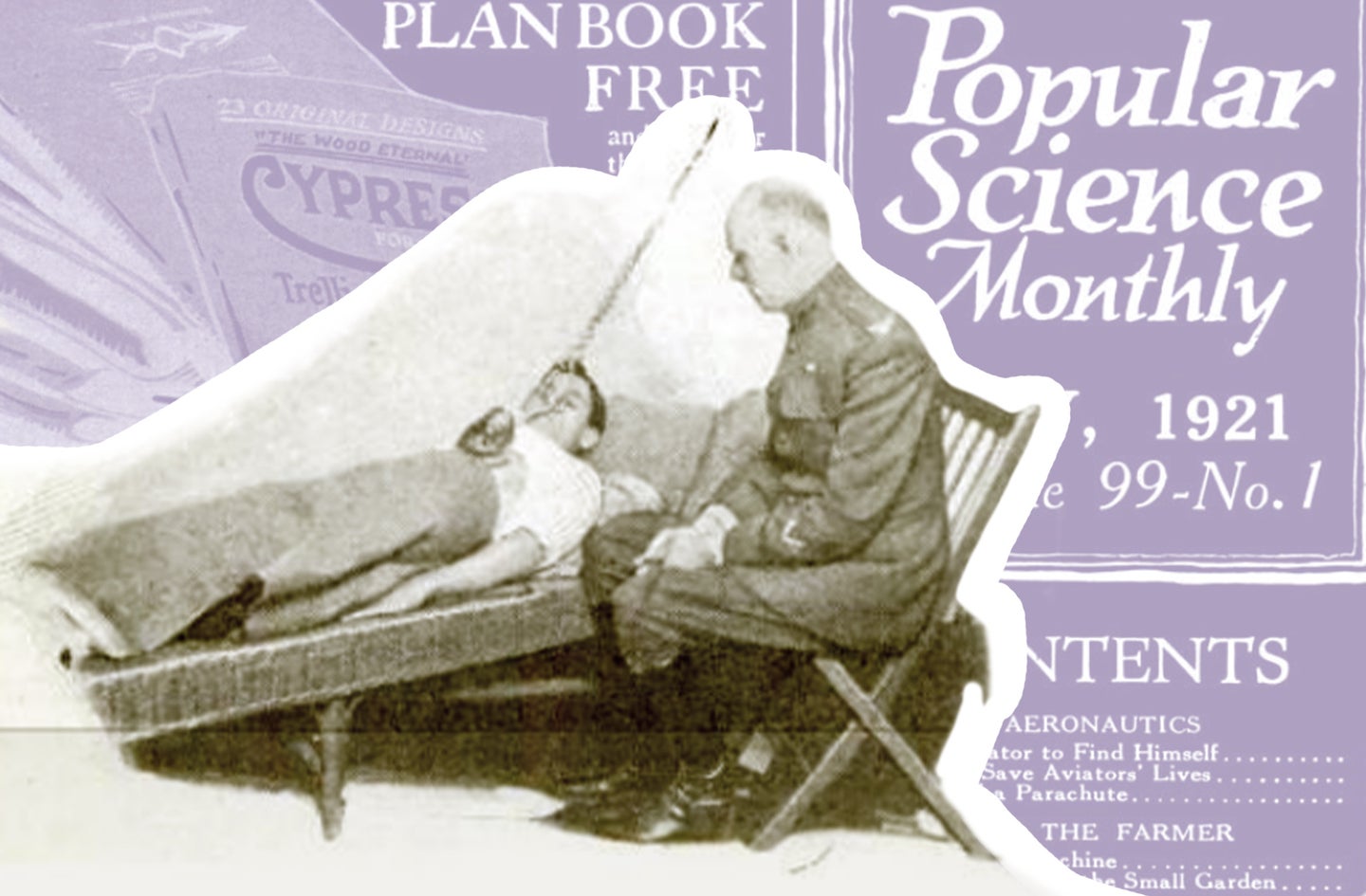

Laënnec would have no doubt welcomed the news reported in Popular Science’s July 1921 issue: “Physicians in New York City may now listen to their patients’ hearts in San Francisco.” A palm-sized transmitter was connected via vacuum tubes and telephone lines to a remote phonograph so that “the heartbeats of a patient may be loud enough to be heard throughout a large auditorium,” a tech Telephony magazine said was initially developed at the US Army’s Signal Corps lab presumably to monitor soldiers. In September 1924, PopSci covered a smaller, cart-contained “stethophone” at an American Medical Association convention in Chicago. These demonstrations promised to expand the reach of medicine, democratizing heart healthcare by making critical equipment mobile and delivering it to remote locales. Over the last century, progress toward that promise has been intermittent, but with recent advances—and the help of a pandemic—it’s been gaining traction.

Despite the novelty of 1921’s stethophone, remote heart monitoring did not really catch on until the Holter monitor—a portable ECG—was commercially released in the early 1960s. The Holter’s form factor, however, precluded it from being practically worn for more than a few days or for anything strenuous. Between tangled wires, taped electrodes, and a cumbersome card-sized recorder, patients would lose patience with the unwieldy device. Even so, it remained the go-to remote monitor for more than five decades.

“Medicine is slow to change and slow to adapt,” notes Francoise Marvel, a Johns Hopkins Cardiology Fellow and CEO of digital monitoring service Corrie Health. For Marvel, a self-proclaimed digital health interventionalist, medicine’s slow pace can be frustrating, even though patient privacy and health safety often dictate the adoption curve. “There had been a lot of stagnation with remote cardiac monitoring,” she says. “And then there came the smartphone.”

[Related: Older adults have a hard time accessing virtual health care.]

Over the past decade, three technological trends have converged to jumpstart efforts to hear distant tickers: significant improvements in wearable sensors, including longer-life batteries; wider availability of high-speed data networks; and the growth of cloud-based analytics, often powered by machine learning, which can deliver results and notifications instantaneously (even from San Francisco to New York). An April 2020 report in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology concluded that remote monitoring for cardiac disorders, “are showing great promise for the early detection of life-threatening conditions and critical events through long-term continuous monitoring.”

There’s mounting evidence, too, that the practice leads to better outcomes, both medical and financial. A 2015 Mayo Clinic report found that discharged patients who enrolled in a smartphone study that required daily blood pressure and weight recordings experienced a 20 percent hospital readmission rate versus 60 percent for the control group. Marvel’s own Corrie Health trials, both published and in progress, have demonstrated similar results using daily blood pressure monitoring as part of a more comprehensive program.

It’s not just Holters and blood pressure cuffs that can monitor heart health remotely—we’re now including everything from Apple Watches to smart patches. StethoMe and ThinkLabs offer puck-sized digital stethoscopes that can be used at home to record and share respiratory and heart rhythm readings. AliveCor’s KardiaMobile finger pad ECG reader comes with a smartphone case attachment. iRhythm offers a pendant-sized patch that sticks directly to the chest and can be worn continuously for up to 30 days. And a century after its stethophone premiere, even the US Army is getting onboard, running remote trials on soldiers using the ruggedized tracker called a Whoop strap.

The monitoring menu may soon expand even more. Gartner forecasts the market for smart clothing could reach more than $2 billion by next year. Hexoskin shirts, for instance, continuously measure ECG and heart rate. German company Ambiotex offers a heart-rate tracking smart shirt. And in 2019, a Georgia Tech team developed a flexible, stretchable electronic system thin enough to be embedded in apparel and capable of measuring a slew of vitals including ECG, heart rate, respiratory rate, and motion. Even with so many technology stars aligning in favor of remote heart monitoring—and mounting evidence that people who are younger or just tech savvy are embracing smartwatches and other biosensors—doctors, seniors, and many insurance companies have generally resisted adoption because the technology can be too expensive, unproven, or difficult to master.

Enter the pandemic.

For all the loss, suffering, and setbacks caused by COVID-19, doctors and patients have learned to lean on telemedicine. In just the second quarter of 2020, the American Medical Association reported that primary care telemedicine visits increased nearly ten times from the year before to 35 million, while office-based visits decreased by 50 percent. A July 2020 report by UK health information company IQVIA indicates that doctors expect to rely on telehealth for 25 percent of their patient visits after the pandemic, up from 6 percent. And a 2021 Pew Research Center report predicts that life will be “far more tech-driven” in the wake of COVID-19, including “the emergence of…an ‘Internet of Medical Things’ with sensors and devices that allow for new kinds of patient monitoring.” Companies like MedWand (physical exams), Butterfly (ultrasounds), and PocDoc (blood tests) already offer digital tools that enable telehealth checkups whether they’re conducted at home, at work, or at a remote care facility.

[Related: Can we make ourselves more empathetic? 100 years of research still has psychologists stumped.]

A century after Popular Science described how the sound of human heartbeats could be transmitted cross country to an awaiting gaggle of white-coated and be-stethoscoped men gathered in a concert hall to catch their first heart concert (not that Heart), remote heart monitoring looks much different now. “I think that COVID-19 hit the gas pedal and showed very quickly, in an emergent setting, that telemedicine could be responsive and could have a benefit,” says Marvel. “And so, I think the door is open, and we need to walk through it and take full advantage of advancing this technology.”