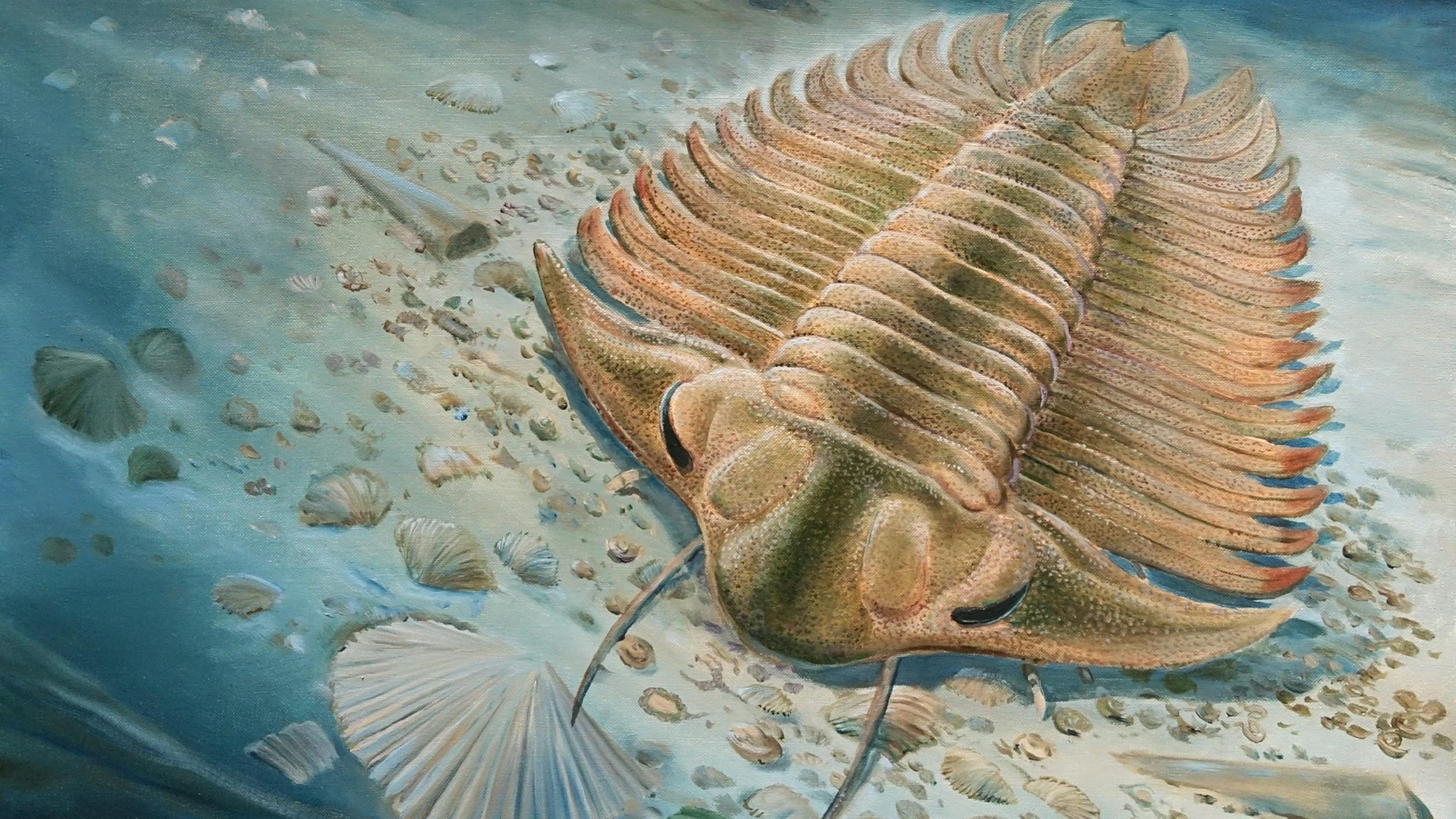

A fossilized trilobite stomach can show us clues to Cambrian cuisine

The 465-million-year-old gut contents reveal similarities between the ancient arthropod and modern crabs.

About 465 million years ago, a now extinct arthropod called a trilobite was eating its way across the present day Czech Republic. After it died, the passage of time actually preserved the plentiful contents of this specimen’s prehistoric guts. A team of paleontologists is using this full fossilized belly to learn more about the feeding habits and lifestyle of these common fossilized arthropods. The findings are detailed in a study published September 27 in the journal Nature.

[Related: Trilobites may have jousted with head ‘tridents’ to win mates.]

More than 20,000 species of trilobite lived during the early Cambrian to the end-Permian period roughly 541 to 252 million years ago. They are some of the most common fossil specimens from this time period, yet paleontologists do not know much about their feeding habits since gut contents usually disappear over time, and until recently there were no known fossil specimens with them intact.

In the study, a team from institutions in Sweden and the Czech Republic examined a fossil specimen of Bohemolichas incola first uncovered near Prague over 100 years ago. Study co-author and paleontologist Petr Kraft from Charles University in Prague had long suspected that this specimen may have a gut full of food intact, but did not have a suitable technique to look inside the trilobite’s innards. Study co-authors and paleontologists Valéria Vaskaninova and Per Ahlberg from Uppsala University in Sweden suggested using a synchrotron in one of their fossil scanning sessions. This machine is a large electron accelerator that produces powerful laser-like x-rays to take high-quality scans of the fossil

“The results were fantastic, showing all the gut contents in detail so that we could identify what the trilobite had been eating,” Ahlberg tells PopSci. “Remains of ostracods (small shell-bearing crustaceans, still around today), hyoliths (extinct cone-shaped animals of uncertain affinities) and stylophorans (extinct echinoderms that look like little armor-plated electric guitars). These are all kinds of animals that lived in the local environment.”

The team believes that Bohemolichas incola was likely an opportunistic scavenger. It also was potentially a light crusher and a chance feeder, which means that it ate both dead or living animals, which either disintegrated easily or were actually small enough to be swallowed whole. However, after this particular Bohemolichas incola died, the circle of life continued and the scavenger became the scavenged. Vertical tracks of other scavengers were found on the specimen. These unknown creatures burrowed into this trilobite’s carcass and targeted its soft tissue, but avoided its gut. Staying away from the gut implies that there were some noxious conditions inside Bohemolichas incola’s digestive system and potentially ongoing enzymatic activity.

[Related: These ancient trilobites are forever frozen in a conga line.]

“We were able to draw conclusions about the chemical environment inside the gut of the living trilobite. The shell fragments on the gut have not been etched by stomach acids, and this shows that the gut pH must have been close to neutral, similar to the condition in modern crabs and horseshoe crabs,” says Ahlberg. “This may indeed be a very ancient shared characteristic of trilobites and these modern arthropods.”

Future studies into trilobites could use similar techniques to look for more gut fills. Since this group is a very diverse group of animals, it can’t be assumed that this particular species is representative of the feeding habits for all.

“This project shows how cutting-edge technology can come together with really old museum specimens. The trilobite was collected in 1908, and has been in a museum ever since, but it is only now that we have the technology to unlock its secrets,” says Ahlberg. “This illustrates not only the rapid technological progress of our time, but also the importance of well-maintained museum collections.”