It was a cold and windy week last January, when a group of Maine lobstermen couldn’t haul in their traps from Jeffrey’s Ledge. The reason why surprised everyone. Over 90 critically endangered North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) had gathered at the ledge, a 62-mile-long underwater ridge about 25 miles off the coast of Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

“This was the first time we’ve known of an aggregation showing up there, I assume they were following their feed pattern,” lobsterman Chris Welch tells Popular Science.

After following all state and federal regulations, using breakaway ropes, setting longer trawls to reduce the number of endlines, and adding purple tracers so any entangled gear could be traced back to Maine, the lobstermen called an emergency meeting.

“We had to do something more to lower the risk. No fisherman wants to harm a right whale, so we’re willing to bend over backwards to make this work,” Welch explains

And that’s what they did.

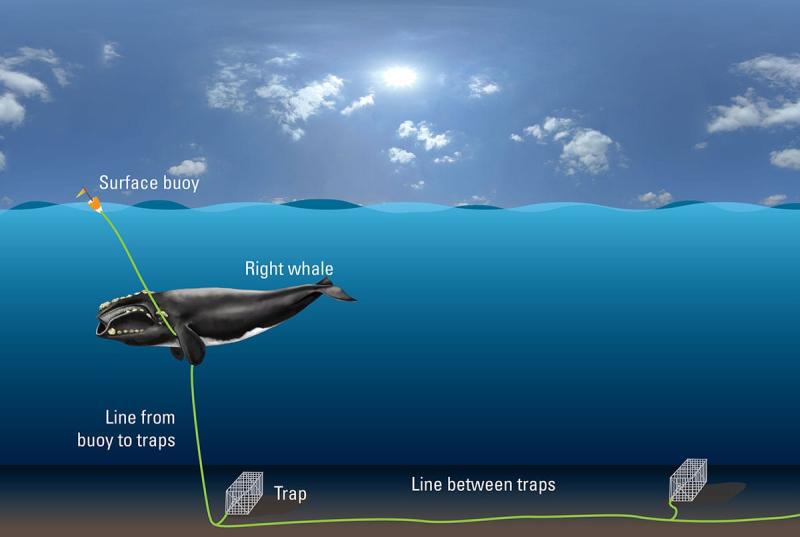

The lobstermen went against fishing protocol by dropping their northeast endlines to reduce the number of ropes in the water. Whales can get tangled in the endlines that connect trawls—a series of traps tied together by rope and linked by two buoys on either end—of their lobster traps.

This choice ensured the whales’ safety, and it was a voluntary act by the fishermen. Had they known the whales were going to be there ahead of time, they could have made other arrangements.

In search of plankton

It’s hard to protect what you can’t find. That’s why research scientist Camille Ross and her team from the New England Aquarium, Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Science, Duke University, and University of Maine are working to improve the predictive models used to find elusive North Atlantic right whales.

“It’s possible that we could have predicted that aggregation out on Jeffreys Ledge in advance,” says Ross.

The team’s study, published in the journal Endangered Species Research, used prey location data to track down these whales. And with a population hovering around 380 and with only 70 reproductively active females, the stakes are high.

“What we did was incorporate right whale food directly into right whale habitat models to help improve the prediction, and it appears it did, which is really exciting,” shares Ross.

Essentially, they found the whales by finding their favorite food first: a krill-like zooplankton in the genus Calanus that are smaller-than-a-grain-of-rice. Calanus’ location and livelihood is dramatically affected by small changes in ocean temperature.

“As the ocean has been warming, and the system has been changing, it has become increasingly harder to know where the bulk of the population is at any given time,” Ross explains. “When observers saw about 25 percent of the right whale population on Jeffrey’s Ledge in January [of 2025], that was just not at all something we would have expected.”

While the right whales themselves may not be thrown off course by a degree or two change in ocean temperature, the tiny critters they eat are dramatically affected by small temperature changes. As the food, which Ross says resembles the character Plankton from Spongebob Squarepants, adapts and moves around, so must the whales. And the tools scientists use to track them.

“This study was proof that prey does improve the right whale models and does increase or decrease predicted densities in areas that we might not have expected.”

Lobstermen’s game of telephone

So,what could have been different out on Jeffreys Ledge in January of 2025 if these better predictive models were up and running? Ross says that after prey was included in the predictive model, they found that Jeffreys Ledge had “increased right whale density from November through January,” critical data that could have been relayed to the fishermen.

That kind of information sharing is what makes collaboration possible and the cornerstone of successful outcomes. It was the Maine lobstermen, for whom fishing is a way of life, who called the Maine Department of Marine Resources (DMR) out of concern for the whales’ safety.

“We would not have known about it had those fishermen not brought back that information,” Ross says. “So many of them are such stewards of the ocean, and they care so deeply about these animals.”

As a result, zero entanglements were reported on Jeffrey’s Ledge in January 2025 because of concern, communication, and cooperation from all sides. Yet without efficient systems, that concern can be lost. And keeping lobstermen informed about right whale locations isn’t always simple.

“The problem with communication with the state is they don’t have a way to text a group of lobstermen,” Welch explains. “Basically, we just went into a phone chain.”

The process is similar to parents texting about their kids, but these lobstermen are alerting each other when they see right whales—not snowflakes. While the seafood industry and conservationists have been at odds in the past, these fishermen are now voluntarily going out of their way to care for these endangered mammals.

“We want to do everything we can to coexist with these whales in harmony,” says Welch. “And we’re doing our best to stay current with information and fish as our livelihood, as well as keep these whales safe, and everything else in the ocean safe.”

Other programs have already shown that science and the fishing community really can go hand in hand. Programs such as NOAA’s Cooperative Research in the Northeast have enabled several collaborations between scientists and fishermen. Fishermen from Maine to North Carolina partner with NOAA in the Study Fleet program by collecting detailed data for scientific research, including environmental conditions, fishery footprints, and developing models.

In terms of what’s next for Ross and her team, she’d like to focus on using more recent data in their predictive models. “What happened the previous year will give us a lot of power in predicting where the right whales might show up the following year, that will give us a lot of really interesting insights, especially as the ocean continues to change.”

One certainty is that many of those who make their living off of the ocean will continue to play a role in protecting those who call the ocean home.