Have you ever walked into a room full of caterpillars? While the answer for most people is probably no, those of us who have may have noticed the insects reacting to the sound of your voice. That’s what happened to Carol Miles, a biologist at Binghamton University in New York.

“Every time I went ‘boo’ at them, they would jump,” she explained in a statement. “And so I just sort of filed it away in the back of my head for many years. Finally, I said, ‘Let’s find out if they can hear and what they can hear and why.’”

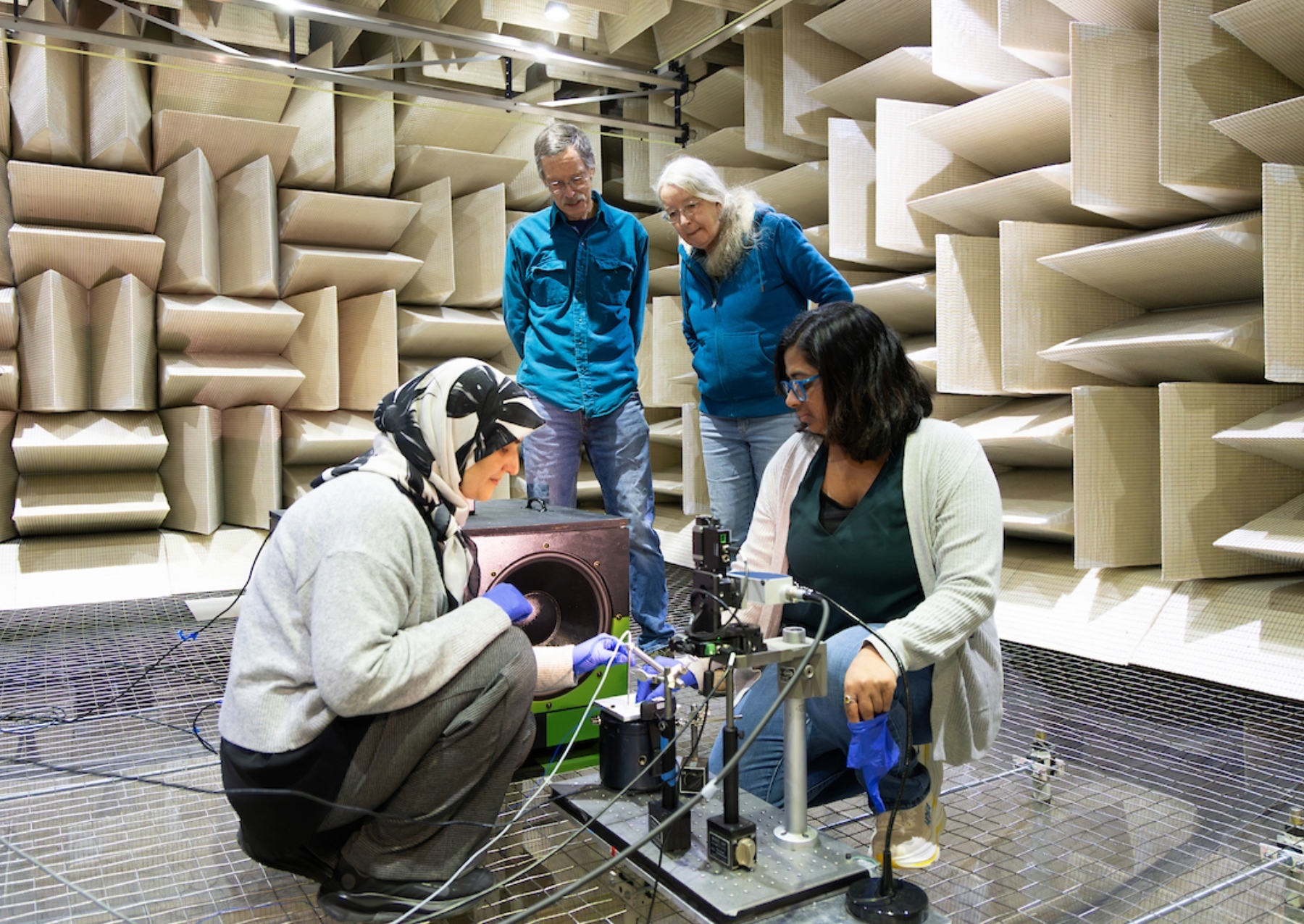

Miles and the team brought tobacco hornworm caterpillars (Manduca sexta) into a room that is among the world’s most silent—the university’s anechoic chamber. Inside of this silent room, the team could precisely control the sound environment, as they worked to pinpoint what sounds trigger the bugs.

The team understood that caterpillars had reactions, but were not sure if it was to airborne sounds or the base’s sound vibrations they can feel with their feet. Because caterpillars often hang out on plant stems, the team had speculated that perhaps they picked up on sounds because of the plant’s vibration.

In the anechoic chamber, researchers can deliver sound and vibration independently of each other and understand the kind of response they solicit. They studied the caterpillars’ response to airborne sounds and surface vibrations at high- (2000 hertz) and low-frequency (150 hertz) sounds.

The researchers found that caterpillars perceive both, though they had a 10- to 100-fold greater reaction to airborne sound compared to the surface vibrations that they sensed through their feet.

The next step was figuring out how they were hearing the sounds, and to do that, the team removed some of their hairs. While that might seem like an odd strategy, many insects perceive sound through hairs that detect how it moves the air. In fact, the team’s caterpillars were less sensitive to sounds after they lost hair on their abdomen and thorax. Miles and her colleagues’ theory is that the tobacco hornworm’s hearing might be evolutionarily tuned to detect the wing beats of predatory wasps.

Back in the world of human hearing, their research could play a role in microphone technology.

The findings were presented at a joint meeting of the Acoustical Society of America and the Acoustical Society of Japan in December 2025.

“There’s an enormous amount of effort and expense on technologies for detecting sound, and there are all kinds of microphones made in this world. We need to learn better ways to create them,” added Ronald Miles, a co-author of the study and a Binghamton University mechanical engineer. “And the way it’s always been done is to look at what animals do and learn how animals detect sound.”