This article was originally featured on Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

Of all the traits that make salmon extraordinary migrants—their leaping prowess, their tolerance of both fresh and salt water, their attunement to the Earth’s magnetic fields—the most impressive might be their sense of smell. Guided by the odors they imprint on in their youth, most adult salmon famously return to spawn in the stream where they were born. No one knows precisely what scents young salmon memorize, but it’s probably some combination of mineral and biological signals, such as distinctive metals and the smell of their own kin.

Several years from now, however, if scientists at the Oregon Hatchery Research Center have their way, some chinook salmon will be chasing a very different scent: the rich, beery bouquet of brewer’s yeast. The alluring aroma of ale is a bid to solve a sticky conservation conundrum: how do you get hatchery-reared salmon to come home?

Though the vast majority of salmon return to their birthplace to spawn, they sometimes slip up. A small portion naturally stray into other streams. “From an evolutionary standpoint,” says Andy Dittman, a Seattle, Washington–based biologist at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “it’s an important alternative strategy” that helps populations survive disaster and expand their range.

After Washington’s Mount St. Helens erupted in 1980, for example, steelhead trout, a close salmon relative, ditched the ash-choked Toutle River and bred in nearby watersheds. And as climate change shrinks Alaska glaciers, salmon have begun to trickle into newly exposed streams and lakes.

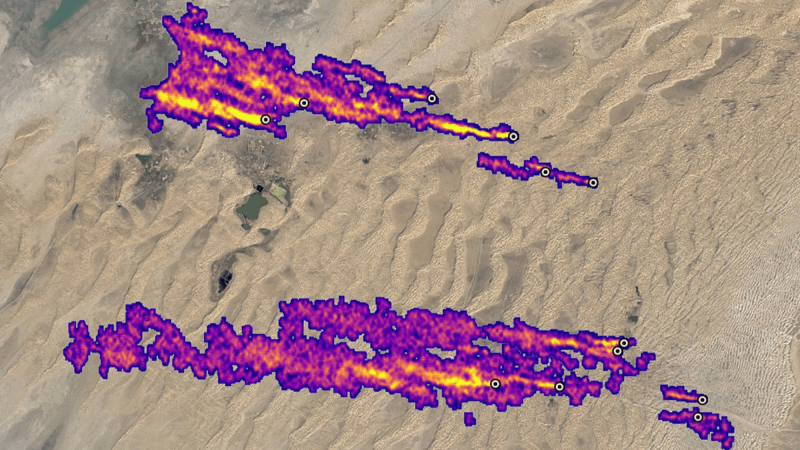

But hatchery-raised salmon take straying to an extreme. Many hatchery fish are released in unfamiliar streams or turned loose during developmental stages when they don’t readily imprint. As adults, these fish often cruise past their home hatcheries and mate with wild-born fish, distorting wild gene pools that have been finely tuned by thousands of years of natural selection. On the Elk River, this problem was historically acute. Some years, recalls Dittman, more than half of breeding fish were hatchery-born salmon that wandered into wild spawning grounds.

In 2016, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife tasked the state’s hatchery research center with solving the problem. Could scientists get juvenile hatchery-reared fish to imprint on a scent of their own choosing, one that would lure them home years later?

Finding the perfect scent fell largely to researcher Maryam Kamran. Much as Pavlov trained his dog to slobber at a sound, Kamran dropped various smelly compounds into tanks full of pinkie-length salmon fry, then added food pellets to get the fish to associate the odors with their meals. If she could then add only the odor to the water and watch the fish still dart with excitement, she knew they could cue into that scent.

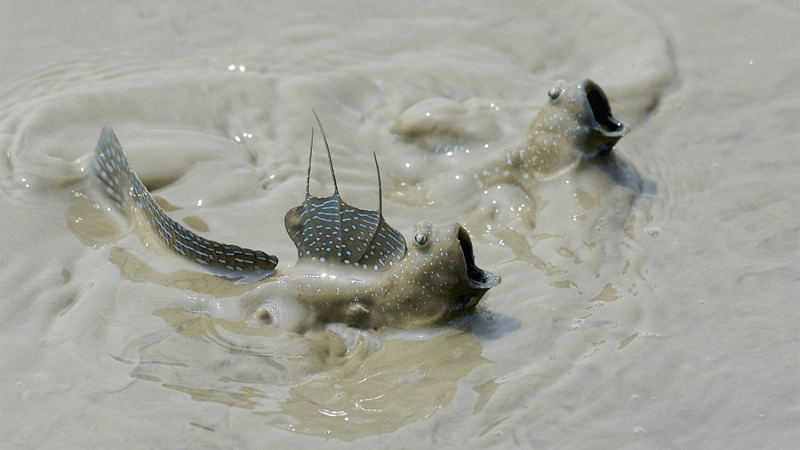

Kamran tested a vast—and occasionally weird—array of aromas, among them extract of shrimp, tincture of watercress, skin of steelhead, and bile of minnow. She mixed and matched various proteins and hormones and pheromones. You’re trying things that will give the fish information, Kamran says. “Is there a predator? Is there a mate? Is there food? What is the quality of habitat?”

In his Seattle laboratory, Dittman supplemented Kamran’s efforts. He placed electrodes on the salmon’s smell receptors, then spritzed them with Kamran’s chosen scents to see how their neurons responded. “Whatever odors we picked,” Kamran says, “we had to see if the salmon noses could actually detect it.”

After several years, a leading candidate emerged: a cocktail of amino acids purchased from a commercial laboratory. In 2021, managers at the Elk River Hatchery released the first chinook salmon fry imprinted on those acids into the wild, along with others reared on minnow bile and other compounds. Yet the amino acid mixture, for all its promise, proved prohibitively expensive to deploy in large quantities. So the quest for a cheap odor continued—which, this spring, led the scientists to beer.

The idea came from Seth White, director of the Oregon Hatchery Research Center. White, an amateur beer maker, knew that brewer’s yeast contains glutamate, an amino acid on which salmon are capable of imprinting. And he knew exactly where to find it in bulk.

One day this March, White visited Newport, Oregon, where the brewmaster of Rogue Ales turned a lever on two vats of beer and poured out pitchers of trub—the yellowish sediment of malt particles, coagulated proteins, and settled yeast that’s left behind by the brewing process. White packed plastic bags of trub in a cooler and drove the hour to the hatchery research center. “I felt like Ulysses on a quest,” White says.

His journey wasn’t in vain, as Dittman quickly found young salmon are highly sensitive to the trub. “It seems to be a good candidate,” White says. “It’s working out really well so far.”

Of course, it’s one thing to get juvenile fish to imprint on an odor, and quite another to get adult salmon to chase it back to their natal hatchery. This past winter, the first males imprinted upon the amino acid cocktail began to trickle back into the Elk River, although scientists haven’t yet analyzed the data. As for the beer, White says the Oregon Hatchery Research Center still has experiments to conduct before hatchery managers consider exposing their fish to trub. If it someday succeeds, though, he already has a name picked out for the brew: Olfaction Pale Ale.

This article first appeared in Hakai Magazine and is republished here with permission.