In October 1914, as gas cars were tightening their grip on America’s roads, Frank W. Smith, president of the Electric Vehicle Association of America, stood before a convention in Philadelphia and declared victory. Electric cars, he said, were “absolutely and unquestionably the automobile of the future, both for business and pleasure.” With mass production and a wider network of charging stations just around the corner, “it is only a matter of time,” he promised, “when the electrically propelled automobile will predominate.”

The future Smith imagined would not show signs of life for nearly 100 years, but it might have come far sooner had America’s industrial leaders stopped treating automotive power as a binary choice between gasoline and electricity. A compelling alternative lay in between. Hybrid power was cleaner and capable of guiding transportation through a more climate-friendly century while batteries and charging infrastructure matured. But by the time a suitable hybrid arrived—just two years after Smith’s proclamation—the world had already committed itself to gas.

Henry Ford and Thomas Edison tried to electrify America’s cars

In 1914, Smith’s optimism seemed justified. All year, E. G. Liebold, Henry Ford’s influential private secretary, had been signaling to the press that Ford and Thomas Edison were teaming up to build a cheap electric car. Ford’s son, Edsel, was overseeing production and the car was set to be released in 1915.

With the two most famous industrialists in America—the leading automobile manufacturer and the nation’s most celebrated inventor—joining forces to mass produce electric automobiles, how could electric cars fail? Earlier that year, Ford and Edison, who had been friends for more than a decade, had even purchased their own electric cars from leading car manufacturer Detroit Electric to publicly affirm their faith in electric power.

The early 20th century heyday of electric cars

At the turn of the 20th century, electric cars were symbols of refinement and technological progress, popular in wealthy urban neighborhoods. Companies like Rauch & Lang, Columbia, Detroit Electric, and Studebaker built electric cars that were meticulously engineered. They started at the flip of a switch. They were quiet and offered a smooth ride through busy city streets.

Charging stations appeared in carriage houses, public garages, and even outside department stores. Popular Science featured such innovations, including a three-wheeled electric car designed to “glide through the shopping district” and a “flivverette”—a miniature electric car, small enough to be parked in a “dog-house.” Electric taxis competed with horse-drawn carriages to ferry passengers through dense urban cores. In an era when roads were still rough and driving was still novel, electric automobiles seemed civilized.

Gasoline cars, by contrast, were noisy and temperamental. To get them started required muscle to turn a stiff crank. They rattled, stalled, and belched exhaust. Early motorists often carried tools and spare parts, expecting breakdowns as part of the journey.

Thomas Edison, like many, believed electric cars would ultimately prevail over gas. Obsessed with improving battery technology, Edison saw the electric automobile as a natural extension of his life’s work in electricity. Even though he was friends with Henry Ford, and encouraged Ford to develop internal combustion engines, Edison reportedly dismissed gas cars as noisy and foul-smelling, praising electricity as cleaner and simpler. In the early years of the automobile age, the quiet hum of electric motors, not the explosion of gasoline, seemed inevitable.

The Ford-Edison electric car that never was

But by 1916, the Ford-Edison electric car still hadn’t materialized. There was some speculation—never proven—that oil tycoons, like John D. Rockefeller, had persuaded Ford to kill the project, but even without such pressure, electric car technology just wasn’t competitive with gas.

Batteries, which were predominantly lead-acid or nickel-iron, were too inefficient, too heavy, and too slow to recharge for the kind of fast-paced, mass-market automotive world consumers were beginning to demand. Plus, in 1916, electricity was scant outside cities.

Clinton Edgar Woods, the forgotten automobile inventor behind the first hybrid cars

But even as gas cars surged, an engineer named Clinton Edgar Woods offered a different solution. Instead of choosing between electricity and gas, he combined them, creating the first commercially viable hybrid vehicle.

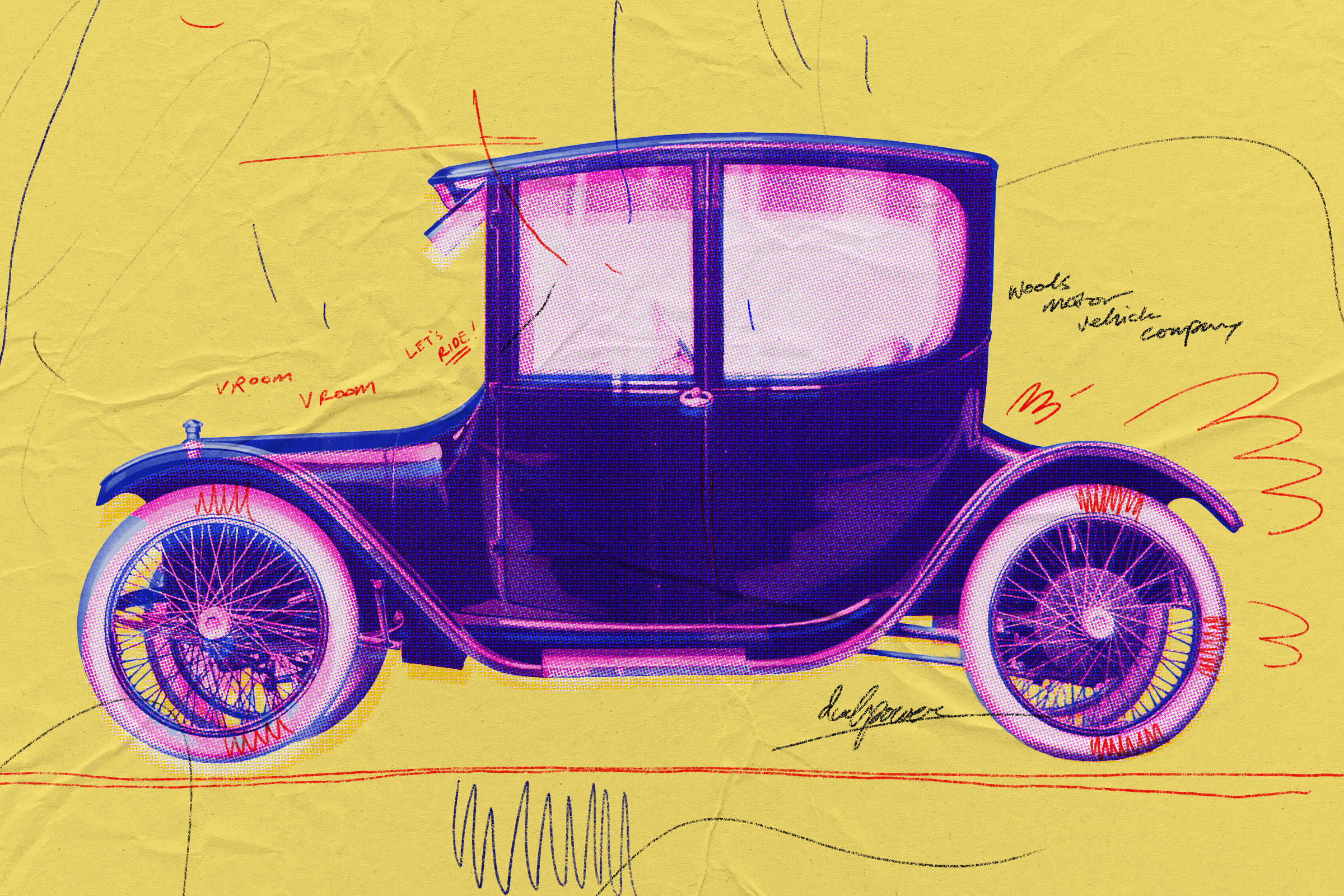

Today, Woods has largely vanished from popular automotive history, but he was an important innovator in the early days of cars. Before he released his hybrid in 1916, Woods had already been at the forefront of electric vehicle design for nearly two decades. In 1899, he launched one of the first electric car companies, the Woods Motor Vehicle Company.

In 1900, before the Ford Motor Company even existed and more than a decade before Smith’s speech, Woods published The Electric Automobile: Its Construction, Care, and Operation. It was a user manual grounded in electric-car operational basics, approaching the subject as if electricity were a foregone conclusion. He explained how to maintain batteries, how to drive efficiently, and how to care for motors. It was not a do-it-yourself guide for a fringe technology; it was a seminal handbook for the automotive future.

The 1916 debut of Clinton Edgar Woods’s first hybrid car

Popular Science announced Woods’s new hybrid car with fascination in 1916. “The power plan of this unique vehicle,” the magazine explained, “consists of a small gasoline motor and an electric-motor generator combined in one unit under the hood forward of the dash, and a storage battery beneath the rear seats.” Woods named the car the Dual Power, referring to its twin power sources. Today, we call it a hybrid.

Woods’s car did not threaten gasoline’s emergence; it promised to leverage it. Where Ford, Edison, and Smith were focused on pure electric, Woods offered a compromise. His hybrid was designed to preserve the elegance and smooth operation of electric motors while conceding the practical power and range that fuel offered. His car offered dynamic braking with regenerative capabilities, using the motor to slow the car and recharge its battery, a feature that would not be seen in cars for another century. It also eliminated the need for a clutch, simplifying operation of the gas engine, just like an automatic transmission. And his design used gas power to recharge the batteries, a must where electricity was unavailable.

Woods’s hybrid was not the first dual-powered car—that claim likely goes to Ferdinand Porsche, who developed a hybrid in 1900, the Lohner-Porsche Semper Vivus—but it was the first attempt to build a mass-producible hybrid. By the time it arrived, however, the market had already made its choice.

In 1916, Ford alone sold more than 700,000 gas cars, while electric car sales collapsed to less than one percent of all cars sold, sliding from the leader in 1900 to a mere niche. Woods’s Dual Power car was one of the last serious efforts to salvage an electric future that was slipping away.

Oil, gas, and our love affair with internal combustion

The world did not abandon electric cars because they weren’t reliable or well-engineered; it abandoned them because gasoline solved immediate problems electricity could not, chiefly speed, range, and fuel distribution. At a time when the competition between electricity and gas was at an inflection point, infrastructure sealed the outcome. It wasn’t until the 1930s that electricity began to spread reliably into rural areas.

By contrast, even in the early 1900s gasoline could be transported in barrels and cans. A gasoline car owner could find gas anywhere from a general store to one of the new fueling stations. Electric cars, on the other hand, were bound to their urban grids, and charging them took much longer than topping off a gas tank.

Woods’s hybrid addressed the recharging limitation, and it offered much greater fuel efficiency than gas-only cars, but it was nearly four times the price of a Ford Model T: $2,600 in 1916 (about $79,000 today) whereas a Model T cost $700 (about $21,000 today). Plus, the Dual Power’s top speed was 35 mph compared to the Model T’s 45 mph.

Had Woods possessed Ford’s mass-production capability, the price gap might have narrowed. Even so, the hybrid’s inherent complexity would have added cost and compromised speed. And yet, such disadvantages might have been overcome, especially in urban settings, had there been the vision and will among America’s industrialists.

Related Stories

100 years ago, ‘ghost ship’ sails baffled Einstein—now they’re making a comeback

In 1928, Eric the Robot promised the robo-butler of the future

A century ago, suspended monorails were serious mass-transit contenders

Why aren’t we driving hydrogen powered cars yet? There’s a reason EVs won.

400 years of telescopes: A window into our study of the cosmos

The road not taken

If we had chosen hybrid designs in the formative years of automotive power, would we have long ago solved the limitations of electric vehicle technology and significantly reduced greenhouse gas emissions? It’s impossible to know, but even today the outlook remains mixed.

In the U.S., electric vehicles accounted for less than eight percent of the passenger car market in 2025, while gas-only vehicles still made up more than 75 percent of the roughly 16.2 million cars sold. Hybrids, meanwhile, have gained steadily—sales surged 36 percent in the second half of 2025, reaching nearly 15 percent of all passenger car purchases. Globally, electric vehicle sales continue to rise, with more than 20 million electrified cars in 2025, mostly in China and Europe. But electric vehicles still represent less than a quarter of all cars sold, a figure that shows signs of plateauing.

As America’s politics swing between looking forward to sustainable power and falling back on our century-long love affair with oil and gas, the hybrid may yet have a role to play in transitioning automotive technology back to electricity—where it started.

Just as Clinton Edgar Woods saw the wisdom of combining the advantages of gasoline and electric power, so today’s hybrids could serve as a bridge while battery technology and charging infrastructure continue to mature. In that sense, Woods’s hybrid is more than a historical footnote; it is a compass pointing us toward the road not taken.

In A Century in Motion, Popular Science revisits fascinating transportation stories from our archives, from hybrid cars to moving sidewalks, and explores how these inventions are re-emerging today in surprising ways.