Next-Gen Space Rovers Do Acrobatics, Look Like Medieval Weapons

The spiky space balls are nicknamed "hedgehogs," though they'll act more like acrobats, leaping and tumbling across the surface of moons and asteroids.

NASA’s past few Mars rovers have been friendly robots with head-like masts and cameras for eyes, easily anthropomorphized and adored. The next generation might be decidedly less cute–they resemble a medieval battle mace.

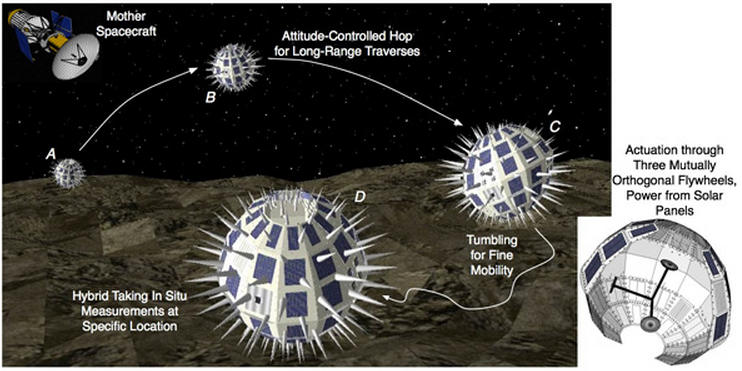

The Phobos Surveyor is a new concept from researchers at Stanford, MIT and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The spacecraft would visit the Martian moon Phobos, or maybe an asteroid. Then one or more mace-ball rovers would deploy from the mothership (which would stay in orbit above) and leap and tumble across the surface of the moon or asteroid. Marco Pavone, an assistant professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics at Stanford, came up with the idea and nicknamed the hopping rovers “hedgehogs” (definitely a cheerier name than mace balls).

Hoppers are a favored design for future planetary explorers because they could cover much more terrain than a rover, and could easily cross canyons and other hazardous areas. With a hopper, you don’t face problems like a stuck wheel, which doomed NASA’s Spirit Mars rover. MIT and Draper Labs have a prototype moon hopper vying for the Google Lunar X Prize: The Terrestrial Lunar and Reduced Gravity Simulator, or Talaris. That one uses ducted fans and compressed nitrogen to hover and hop around.

The hedgehogs would not need much energy to hop on Phobos–the Martian moon’s gravitational field is 1,000 times weaker than that of Mars–so their inertial spinning would propel them easily. Here’s how it would work: The Phobos Surveyor, which Stanford’s news service describes as coffee-table-sized with two umbrella-shaped solar panels, would travel to Phobos and map the moon’s terrain. After a few months, it would deploy five or six hedgehogs, one at a time, each a few days apart. The spacecraft would communicate with each other to determine each hedgehog’s position, and determine where it should hop next.

Each hedgehog contains three discs that rotate on all three axes, and spinning them at varying speeds produces an inertial force that causes them to move. A quick spin can cause a hop, and spinning even faster causes them to bound across the surface. Slight wheel spins force the hedgehogs to tumble slightly. Why the spikes? They could ensure the hedgehogs can gain purchase in any terrain, whether it is hard and rocky or soft and sandy.

Combining a global view with on-the-ground measurements has worked quite well for NASA’s Mars program, and this would work in a similar fashion. The Phobos Surveyor might measure chemical elements, while the hedgehogs might study the terrain with microscopes or other tools. All this would help scientists learn more about Phobos’ past.

It could also have much broader benefits for the space program, too. Because of that weak gravity field, Phobos might be a convenient first target for human visitors. This mission would provide a lot more information about what the moon is like.

The Stanford team already has a few hedgehog prototypes, and will test the latest one using a crane to simulate lower gravity. Flour will be a stand-in for asteroid dust, and the researchers will also bring in rocks and dirt to simulate Phobos. It’s part of NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts Program, which has spawned several other creative ideas we would love to see. The team plans to present a paper describing the concept at a conference this spring.