This Is What The Depression Sounded Like

Digital birds reconstruct the soundscape of famous naturalist Aldo Leopold.

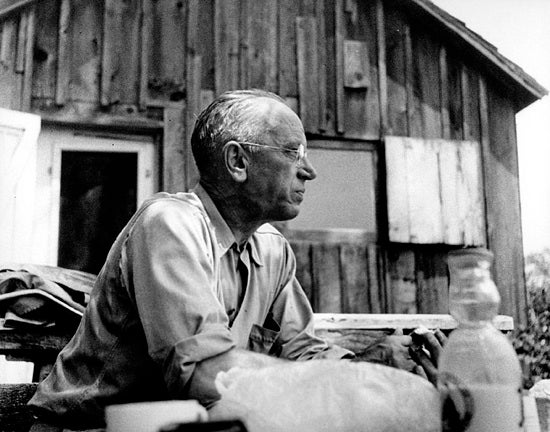

The great American naturalist Aldo Leopold once wrote that he was glad he would not be young in a future without wilderness. Indeed, he may not have been thrilled to know the sonic environment he enjoyed each day is gone; the sound of highways now mingles with birdsong, which itself has changed with the redistribution of species. But he took such detailed and copious field notes that we can recreate that environment, hearing the sounds of nature as Leopold himself would have.

This “resurrected soundscape” is the first sonic setting to be recreated from real data, rather than from informed imagination, according to researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Leopold, regarded as the father of wildlife ecology, would sit on a bench before sunrise at his Wisconsin shack during the 1930s and ’40s. He would jot down the morning chorus of birds, noting the light level and time when he heard the first calls. He even mapped the birds’ distribution around his Sauk County, Wisc., home. Stan Temple, a University of Wisconsin-Madison emeritus professor of wildlife ecology, and Christopher Bocast, a UW-Madison graduate student and acoustic ecologist, worked with 30 minutes’ worth of Leopold’s notes and compiled a list of species and sounds. The recordings are compressed into a five-minute clip, so it’s a bit more of a din than Leopold would have heard. The background noise comes from a rural Wisconsin setting, and the bird calls came from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Macaulay Library.

The detailed writings of naturalists have long served as a database for ecologists and historians curious about environmental changes over time. Henry David Thoreau’s interest in phenology, the timing of seasonal changes, is helping inform botanists’ understanding of climate change. Similarly, comparing what Leopold heard with what you can hear today can help scientists draw comparisons between past and present.

“Leopold recognized that you can get a pretty good sense of land health by listening to the soundscape,” Temple told UW News. “If sounds are missing and things are there that shouldn’t be, it often indicates underlying ecological problems.”

[via ScienceDaily]