A poorly applied window tint job or protective film layer with bubbles and uneven application is a cringe-worthy eye sore. The truth is, as I’ve recently discovered in a visit to XPEL’s San Antonio, Texas headquarters, applying window tint is not nearly as easy as it sounds. It’s nothing like affixing a smartphone screen protector or even hanging wallpaper. While both of those tasks carry their own unique challenges, they don’t match the technique and training it takes to ensure the film is smooth and professionally applied.

That’s not the most interesting aspect of XPEL’s high-tech process, though. Inside the research and development center of the main building, researchers like director of technology Ajay Vidyasagar and lab manager Juan Araiza are doing everything they can to put the company’s protective film to the test. Wire brushes scratch the coating to assess its “self-healing” properties and a machine affectionately called “the Gravelator” shoots a steady stream of rocks at sample pieces to see if the paint underneath is damaged.

It’s all about chemistry, and specific procedures that create a repeatable shield for vehicles and more.

Macromolecules and reversible covalent bonds

XPEL’s paint protection films are engineered with cutting-edge polymer science. In case you’re not familiar with polymers, Case Western University’s engineering school describes polymers (also called macromolecules) as “the long molecular chains that provide the building blocks for all the matter in the world that isn’t metal or ceramic.”

Protective paint films like XPEL’s have to adhere to the metal and non-metal surfaces of a car and keep bird droppings, acid rain, and rock chips from damaging the finish. The durable and stretchy material is a multi-layer cake made from incredibly thin bands, each a fraction of the thickness of a strand of human hair. The top layer of the film contains elastomeric polymers, which have the ability to “self-heal” when exposed to heat.

“Our films are engineered to have a synergistic interaction between reversible covalent bonds, hydrogen bonds or ionic bonds present in the formulation that help achieve a high degree of self-healing and mechanical performance,” Vidyasagar says. “The intrinsic self-healing mechanism utilizes the exchange of dynamic chemical bonds and supramolecular physical interactions between damaged interfaces within the polymer chain, enabling the polymer chains to reconnect and return to their original pristine condition, repairing minor surface damage like swirl marks and light scratches. This ensures that the film continuously protects the vehicle while maintaining a flawless finish.”

To break it down further, Vidyasagar explains that polymer chains, in general, are naturally inclined to knit back together. By adding thermal energy, you can expedite the process, thereby helping the molecules to move faster and return to a smooth surface. Let’s say you’re off-roading in Texas, for example, and it appears that your vehicle sustained unsightly scratches from mesquite thorns and other brush. Once back home, aim a heat gun or hair dryer at the scratches and they “melt” right out.

In a pinch, Vidyasagar says, you can even use hot water (70-80 degrees Fahrenheit) to coax the polymer chains to reknit. However, the heat gun or hair dryer is more consistent and likely to offer the best result. At the XPEL factory testing center, if the film doesn’t self heal, it’s not shipped.

Supplanting the “car bras” of the 80s

Today’s window tint and paint protective film are challenging to apply, requiring a deft hand and practiced technique. The nearly-invisible urethane film replaces the black vinyl “car bras” of the 1980s. Picture a Pontiac Firebird or Chevrolet Camaro IROC-Z; it seemed that just about every one of them was wearing physical paint protection, and it wasn’t attractive. Modern technology means a flapping material cover-up is no longer required, and it lasts a lot longer.

Starting with a soap and water solution, trainer Travis Willams showed me how to prep the surface of a Porsche hood for the protective layer. Then, using a hand-held plastic squeegee, Williams ushered the soap and water from underneath the film to the outer edges, stretching the material slightly to hug the corners. I did pretty well, following Williams’ lead for a bubble-free experience.

XPEL measures its film in mils, which is not short for millimeters (as confusing as that may be). A mil equals one-thousandth of an inch, or 0.0254 millimeters. For context, a trash bag in your kitchen most likely ranges between 1.2 mils and 1.7 mils. XPEL’s protective film is between 7 and 11 mils thick.

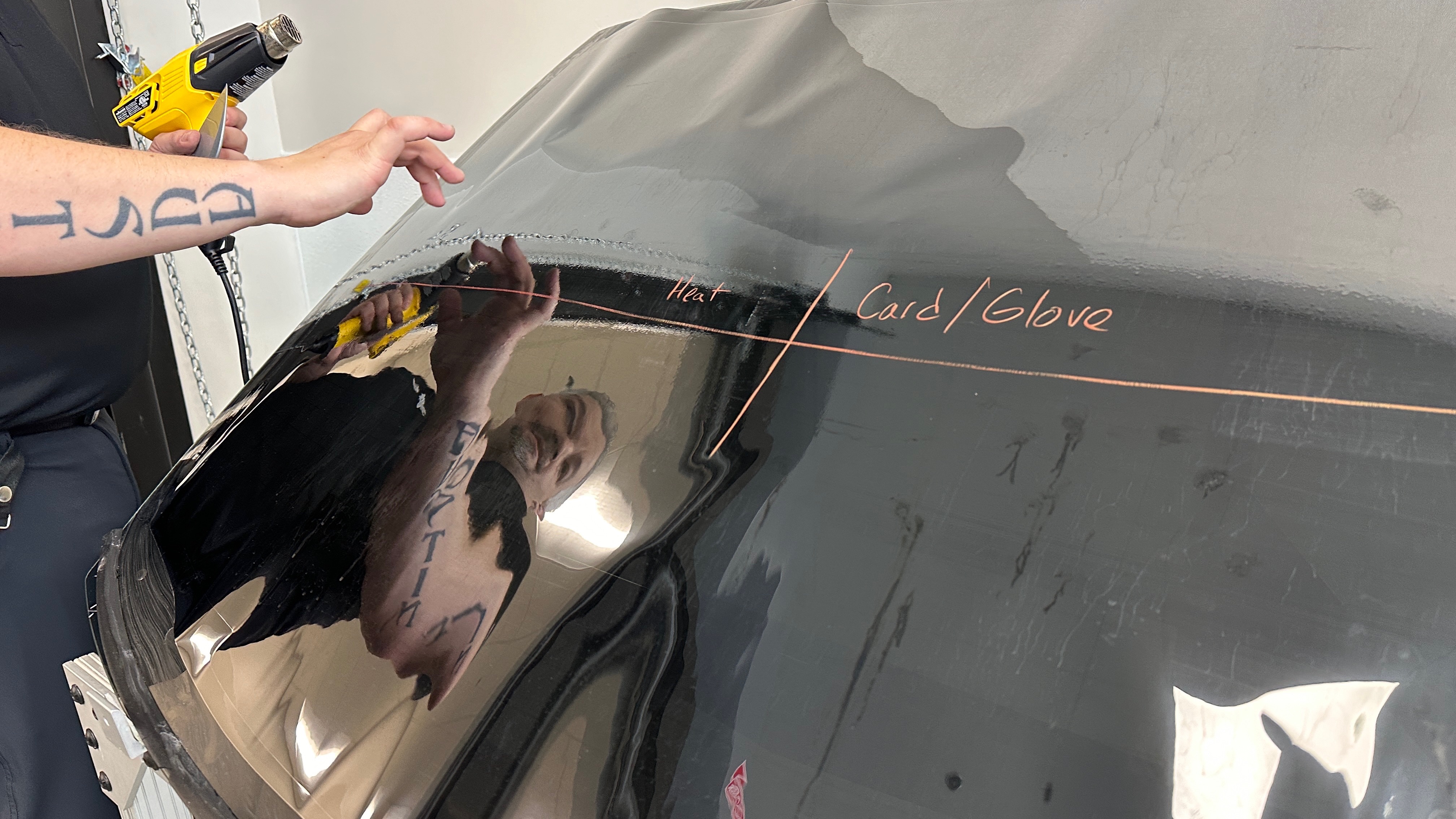

Window tint is much more challenging, requiring a steady application of heat while using a plastic tool or gloved hands to push the tint precisely into place. One wrong move and the tint can go awry, which means the entire sheet has to be removed for a fresh start. After trying (and failing) to apply on the first try, I think I’ll leave that to the professionals.